“I want to write fiction that has no obvious message, that cannot be made smaller, that resists the single interpretation…That arrives out of the total human encounter, as far as that can be gathered and held in language.” —Andrew Miller

If you’re like me, you read the acknowledgements and author bio when you finish a novel. I can’t help myself; I yearn for insight into the creator of the world I was just inhabiting. Basically, I want to get into the author’s head and understand their motivation for what and why they write.

Recently, I became aware of Andrew Miller, a contemporary British author who has written works of fiction that have garnered critical acclaim. Beyond the awards, I was drawn to Miller’s works because he is achingly transparent in articles and blog posts about his approach to writing. Miller does not want to be pigeonholed as a writer of a specific type of book or genre and would rather his words literally speak for themselves with the reader as the final arbiter of meaning.

If you’ve never read Miller and you appreciate novels that explore the human condition in all its messy glory with intentional language, then you must pick one of the titles below. And while Miller wants nothing to do with labels, his writing consistently makes an absolute promise to leave you with more questions than answers.

The Land in Winter

“The time? He sifted it from the air, from the many small clues it gave. Presences, absences.”

The start of this book describes a character waking up in his house without a watch trying to figure out the time of day and sets the stage for the atmosphere of the stories that will unfold. Miller is inviting the reader to puzzle out the status of two married couples from the small clues, presences and absences of daily life juxtaposed against a catastrophic winter in 1960s rural England. Not unlike a slice-of-life portrait to be contemplated in a museum, Miller leaves the interpretation to the reader.

Miller’s most recent novel, published in 2024, has been longlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. Readers looking for lush language and observational, slower-paced musings on the complexity of marriage will enjoy this novel.

Now We Shall Be Entirely Free

“I often have no idea of where I'm going with a novel, or I have the very slightest intuitive feel for where to go, like a breeze on the cheek, or the calling of something, some night bird, in the far woods.” —Miller

A soldier returning to Scotland from the Napoleonic Wars hoping, if not to heal emotionally from the atrocities he experienced (and inflicted), at least to heal physically. While that could have been enough for Miller to chew on, he throws in a nefarious entity that has followed Cap. John LeCroix to the one place in the world where he thought he was safe.

This novel is authentically Miller in that his story crosses genres to its finish line and gifts the reader a suspenseful, tension-filled story that blends thriller, romance, and a mental health journey while continuing to explore how to be human in these circumstances.

The Crossing

“It is, I think, in the moment before we can say, ‘it’s this’, that we are in the more interesting place. As we settle on a thing we often miss it.” —Miller

Enigmatic. This word comes up often in reviews for Miller’s works, the endings of his novels and in this case, for the main character of Maud in The Crossing. We meet Maud in her university days through an encounter she has with her future husband, Tim. She is fascinating and unknown to Tim and he can’t help but be drawn to her. The first half of the book is spent trying to understand this woman who loves science and boating but is not prone to emotions through Tim’s eyes.

After a life-changing event happens to both Tim and Maud, the focus of the story changes to trying to understand Maud herself when she is alone on a journey on the sea. Whether Maud is ultimately knowable or even relatable is left up to the reader to decide as we witness her grappling with grief and the open ocean.

The Slowworm's Song

“When I started all this, still reeling from the letter, threads of panic in my chest, I wanted ... what? To get in my side of the story before they got in theirs? One more, one last go at making sense of it all?”

What is one to do when a letter innocently arrives in your home that will upend life as you know it? Write a letter of your own, of course. In this selection, Miller offers a novel in epistolary form.

Stephen is a British soldier who was sent into the Troubles in Ireland in the 1980s. He thought he left those events behind, but the past catches up with him. He can only take control of the narrative by explaining his role to his daughter and in so doing, addressing the trauma within himself.

Pure

“Surely nothing more offensive to such a reader than to have the book's meanings presented like a crude caption beneath a painting, something that 'explains' what she was quite capable of deducing.” —Miller

When Jean-Baptiste Baratte is commissioned to essentially remove a cemetery in a poor district in Paris, it seems fairly straightforward. However, in these years before the French Revolution, this deceptive scenario lends itself to Miller’s keen eye for the underlying struggles of the people of that time that will boil over into bloodshed.

But don’t expect Miller to offer up the cake and eat it too. He merely lays bare the human emotions and leaves the rest up to the reader.

Oxygen

The concept of siblings returning home to tend to a dying parent is not necessarily unique, but in Miller’s hands it is altogether a visceral reading experience. A mother reflecting on her life and her relationships with her sons. The two sons living in different places coming home to say goodbye to their mother and own the life choices they have made.

Miller indulges in the relatable vice of being human in seeing all the missed opportunities and failures of a lifetime and whether that can inform better, more confident choices in the future for those who survive their pasts.

The Optimists

“Writing is how you transform yourself, the world. It’s your politics.” —Miller

Clem is a photographer who was assigned to document the atrocities of the Rwandan genocide. He begins to have trouble seeing physically, and emotionally, and retreats back to London with questions about humanity and himself.

The parallels between a photographer as an unbiased reporter of the best and worst of human acts and a writer laying bare the same without judgement cannot be lost here. Are these positions of power that should be used for opinions or merely as a magnifying glass for others to interpret? Miller proposes both.

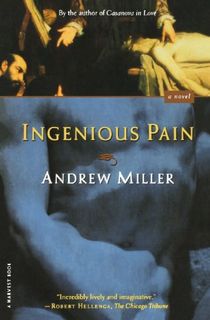

Ingenious Pain

This debut novel of Miller essentially introduces the reader to the high levels of speculation that will guide him through the rest of his works. The device of a main character who doesn’t feel pain emotionally or physically is a delicious opening on commentary for what makes us human.

The story starts with the end of James Dyer, a surgeon who seemingly escaped having to endure pain like the rest of us. Thus, the idea of whether escaping this pain leads to freedom or disconnection begins. As with all of Miller’s novels, it’s not for him to say.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for Early Bird Books to celebrate the novels you love.