When iconic sleuth Nancy Drew was dreamed up in 1930, no one—not even her own creator—believed the character would have a lasting impact on the literary scene and society as a whole. Publishing mogul Edward Stratemeyer first created Nancy, along with a team of freelancers, to be a female counterpoint to the Hardy Boys.

His expectations for capturing a female audience were wildly exceeded: Nancy Drew went on to sell 80 million book copies, become an iconic book character costume for Halloween, and inspire dozens of adaptations—most recently, the film Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase. The beloved detective has had a place in the hearts and minds of readers for close to a century now.

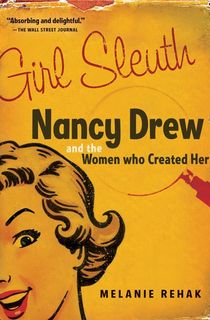

Girl Sleuth by Melanie Rehak aims to finally shed light on the enigma that is Nancy Drew—from the character’s origins to her massive popularity. Though the amateur detective is instantly recognizable, the true story of her creation has long been shrouded in mystery thanks to the efforts of Stratemeyer Syndicate—the publishing company that originally owned the rights to the character. The Syndicate has guarded many details, including the true identity of Carolyn Keene, which was the pseudonym for the author(s) who contributed to the Nancy Drew series over the years.

Related: 5 Beloved Characters Who Shaped Our Identity

Mildred Benson is specifically highlighted as one of Nancy’s creators. Though she never quite received the recognition she deserved, Benson penned the first 23 Nancy Drew books under the Carolyn Keene pseudonym and is considered to be responsible for developing the character that we know and love today. Harriet Adams, an editor at Stratemeyer Syndicate, is also an important part of the story, as she took it upon herself to advocate for the character. In many ways, these women represented the clashing of societal ideals about feminism and the role of women: Benson sought to make Nancy independent and daring, while Adams shied away from making the character “too bold”. Ultimately, the appeal of the character that Benson had developed couldn’t be denied. Clever and capable Nancy Drew struck a chord with her female readers, who saw themselves in her.

The following passage describes how Nancy Drew was received in popular culture, both by satirical publications and the readers who adored her.

Read the excerpt below, and then download Girl Sleuth.

By the late 1970s, Harriet had taken to referring to Nancy Drew as her daughter in interviews, and the sleuth had become Harriet’s way of communicating her values to the world at large. She was as protective of Nancy’s image as she was of her own, whether it was in new titles or a revision that was still being worked over. “I feel you overstepped your position in trying to revamp Nancy’s character,” she wrote to her old nemesis at Grosset, Anne Hagan, in 1972. “She is not all those dreadful things you accuse her of and in many instances you have actually wanted to make her negative.” The following year, she was incensed on her “child’s” behalf yet again: “Anne, are your remarks intended to mend story holes or do you get some sadistic fun out of downgrading and offending me? It will take me a long time to live down the remark ‘Nancy sounds like a nasty female.’” She was even more distressed about the revisions to The Clue in the Crumbling Wall: “I must tell you quite frankly that you cause me a great deal of unnecessary work, which brings my creation of a new story to an abrupt halt. There are hundreds of unwarranted word changes which are apparently whims on your part, like ‘peer out’ to ‘look out.’ What bothers me even more is your supposition that you, not I, know what Nancy, Mr. Drew, et al. would say or do, like deleting Nancy’s lovely gesture of putting an arm around an elderly woman who has just done the young detective a great favor. In the future will you please stick to the functions of an editor and not try steering my fictional family into a non–Carolyn Keene direction.”

But if Harriet thought Nancy’s treatment by Grosset & Dunlap was rough, she was in for a big surprise. By allowing her beloved detective to move into the cultural mainstream as a symbol to girls and women everywhere, Harriet had unwittingly opened her up to the so-called highest praise of all: imitation—or, rather, parody. It’s not difficult to imagine how Harriet must have felt in the summer of 1974, when that bastion of foul-mouthed humor, National Lampoon magazine, decided to set its sights on Nancy in the June “Pubescence” issue. Along with ads for “I am not a crook” Nixon watches ($19.95 apiece) and features ranging from “VD Comics” to “Masturbation Foto Funnies” appeared “The Case of the Missing Heiress,” in which Nancy Drew and Patty Hearst meet up. Hearst, still on the run with the Symbionese Liberation Army after her kidnapping some months before and a spectacular robbery at a Sacramento bank, had recently made headlines yet again by participating in a shootout at a sporting goods store. In the Lampoon version, Nancy was called in to deduce the identity of Hearst’s kidnapper, who turned out to be not the SLA but her own newspaper magnate father. The SLA got involved in the plot regardless, trying to kill Nancy along the way by giving her an overdose of Midol, the over-the-counter remedy for menstrual cramps. Full of racial epithets and outrageous situations, the story wound down with a gentle mockery of the teen sleuth’s propensity for emerging unscathed from any situation.

“There’s still one thing I don’t understand,” Bess Marvin called from the rumble seat as they motored east for River Heights . . . “When the SLA gave you that fatal overdose of Midol, how come you still could set the fire and escape without being knocked out?” “That’s still a real puzzler,” Nancy laughed pertly. “I still haven’t been able to figure that out for myself!” With a chorus of appreciative chuckles, Nancy and her chums sped merrily into the darkening landscape, little knowing that Nancy’s next adventure, The Secret of the Fatal Motoring Mishap, would solve more than a few mysteries.”

Depending on how you thought of it, Nancy had either scraped rock bottom or reached the very height of popular culture. But when the New York Times Magazine ran another parody, “The Real Nancy Drew,” in October of the following year, Harriet could not keep quiet. The piece, which ran as a mock interview with an aged Nancy, did everything from imply that the sleuth had grown up to be a lonely old maid (“Old age has its compensations and royalties,” she answers jauntily to that question) to state outright that George was a lesbian. “George didn’t come clean with me, pretending she was a tomboy, when actually she was a . . . Q: She didn’t come out of the closet? A: Kept it locked and threw away the key.” It was too much for Harriet to bear. She wrote a letter to the Times, berating them for violating their own standards as well as hers, and for “belittling and reversing the principal characters in this famous series (which I write under the name Caroline [sic] Keene) with innuendoes of sex and pornography. Surely the millions of loyal Nancy Drew fans of all ages will find this travesty most distasteful.” In her reply, the parody’s author simply piled on more. “I did not tell all,” she wrote. “Now that my back is up against the haunted house, I feel it is my duty to set the record straight . . . it was Nancy Drew who backed Calvin Coolidge all the way, who was the first woman to wear a tube dress in the jungle in order to be more feminine, who photographed Bomba the Jungle Boy for Life magazine (making him an overnight sensation), who personally slapped Bertrand Russell to teach him that infidelity doesn’t pay.” Nancy had officially gone from private to public property.

Books covers of The Clue of the Tapping Heels, The Ghost of Blackwood Hall, and The Clue of the Broken Locket.

As much as the besmirching of her prized “daughter” bothered Harriet, it was good for business. By 1976 sales of the series had been increasing steadily for four years, reversing the gradual drop-off that had been happening since the late 1950s. “Nobody’s sure why,” one reporter wrote. “Except mothers who grew up with the books now seem to be buying them for their daughters.” Often these mothers were unaware that the books had been revised, but in any case the new Nancy seemed to be exciting enough for the younger set. The nostalgia factor was still running high, too, as women’s libbers fell more in love with Nancy than ever. “In the Drew books, there were mysteries to be solved and she solved them,” the president of NOW told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “[Most juvenile heroines] never did anything. I think the idea that she may have had a lot to do with liberating women is probably the case.” A former staffer at Ms. opined that “Nancy Drew, whose exploits have filled the contents of 50 books, is one heroine who qualifies in many ways as a role model for young feminists,” leaving the reporter on the story to conclude that “her daring, self-confident, competent personality may be increasingly attractive to today’s ‘new woman’—and today’s children.”

Part of her appeal, it seemed, was that she didn’t make a big fuss about her independence. “Their impact on me was simply that I read every one I could get my hands on,” explained one fan, now twenty-six years old. “I was excited by what she was doing. I didn’t realize how feminist they were because I sort of figured that’s the way the world was.” Taking her passion to the extreme, another woman wrote, “I can foresee the day when Nancy Drew stories will be transmitted via satellite to colonies on the moon . . . She’ll be 19, wear a space helmet, and drive her own space ship. And if the space ship runs short of atomic energy . . . Nancy will say: ‘Don’t worry . . . only one rocket is out.’”

This passage highlights Harriet Adams’ efforts to protect Nancy Drew on behalf of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Not only did she keep the sleuth’s true authorship hush-hush, but she also went above and beyond to try to keep her reputation squeaky clean. However, as the many women interviewed for Girl Sleuth point out, Nancy Drew remained a role model for them regardless. The character’s confidence and competence inspired generations of readers.

Want to keep reading? Download Girl Sleuth now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for Early Bird Books to continue publishing the book stories you love.

Featured image from "The Secret in the Old Attic" by Carolyn Keene