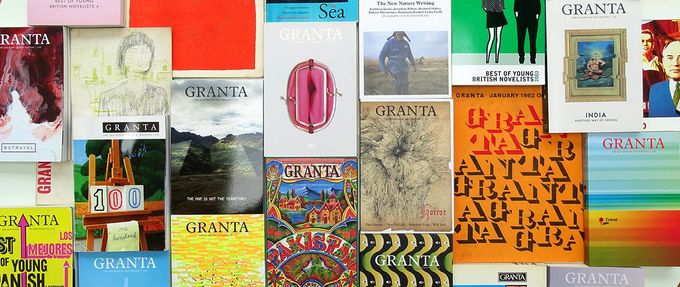

Granta magazine was founded in 1889 as The Granta, a student literary journal at Cambridge University. It published works by such great authors as A.A. Milne, Michael Frayn, Stevie Smith, Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath.

In 1979, the magazine switched from being a student publication to the literary quarterly that it is today. Each issue includes the best authors discussing one aspect of daily life. Ten years later, Granta Books was founded as an imprint devoted to the same ideals as the original magazine: to publish, in the words of founder Bill Buford, “only writing we care passionately about.”

Granta has remained devoted to promoting new and fresh names in literature and to only publishing the highest quality writing. For an intimate, small press, Granta has an outsized number of prize winners, including 31 Nobel Prize laureates, and a huge cultural impact on the literary scene.

As a special opportunity for Early Bird Books readers, Granta is offering a six month subscription for only $1! Claim this amazing deal below. Plus, for a limited time, Granta's new story, “Burning Mao” is free to all readers. Read on for an excerpt of the story, then subscribe for just $1!

Read an excerpt from “Burning Mao” by Fernanda Eberstadt below!

The summer of 1977, when I was sixteen years old, I started work at Andy Warhol’s Factory.

I was a teen stalker, a fantasist who mostly preferred sitting on a stoop opposite someone’s house, noting the street-scene in my diary, to actually meeting the person inside, and Andy had long been one of my simmering obsessions.

My parents – New York society people with an interest in downtown art – had first met Andy in the late fifties, when my father was working as a fashion photographer and Andy was still an illustrator dressing windows for Bonwit Teller. My father liked to say that back then he’d thought Andy Warhol an embarrassing little creep whose determination to be famous was clearly doomed. But my mother had a taste for oddball dreamers and she and Andy became friends; she appeared in one of his 1964 Screen Tests. I’d been raised on her stories of the Factory – the silver-tinfoil-walled spaceship where Andy, pedaling on his exercise bike, swigged codeine-infused cough syrup and watched his superstars squabble and self-destruct. Watched and subtly egged them on. At a certain point, my mother got spooked by how many of his beautiful, lost young creatures ended up dead.

In 1968, Andy was shot by Valerie Solanas and he too, briefly, died. It was a time when America’s chickens, in Malcolm X’s phrase, seemed to be coming home to roost – Andy’s shooting was edged off the front pages by Robert F. Kennedy’s two days later – and when Andy came back from the dead, with his insides shattered and sewn together again, he was seemingly cured of his taste for watching other people detonate.

On 7 December 1976, I finally succeeded in pestering my parents into introducing me to Andy Warhol.

By then, they had devolved into merely social, semi-professional friends who exchanged poinsettia plants at Christmas, and the Andy I had wanted to know – the ghostly cyclist who could mesmerize you for eight hours with a flickery image of a skyscraper – had been supplanted by the art-businessman flanked by pinstripe-suited managers. And I too was in a different phase. By the time I actually made it to the Factory, I was less interested in Andy than in dancing at Studio 54 with his managers.

Our first meeting was at La Grenouille, a fancy French restaurant in Midtown. My parents had invited Andy to dinner, and later that night, I wrote my first impression of him in my diary. Andy was ‘standing there in his dinner jacket and blue jeans, tape recorder tucked under his arm, looking shy and uncertain but friendly’. He had brought as his date Bianca Jagger, gorgeous in a purple fox stole and a gold lamé toque. They ordered oysters and a spinach soufflé, which she sent back because, as she explained to the waiter, it was affreux. ‘Halfway through dinner Mummy asked me to switch places with her so I could talk to Andy. Andy said something about my mother being “mean” not to let me sit next to him before. So we talked the rest of the evening. I was a little shy and ended up feeling oddly depressed and dispirited, sort of drained. He said I looked like a movie star, had I ever thought of being one. That seemed like the sort of thing he says to about five hundred people a week . . . He asked me to bring down my whole class to the studio – that too I found depressing. I asked “Why don’t you come to Brearley [the private girls’ school where I was in eleventh grade]?” He said no, he could never do that, something about being too shy. I said, “Well, a lot of them are really awful.” He said, “Well, bring the awful ones too.” He’s very easy to talk to, I kept saying things I wished I hadn’t.’

My mother had told Andy I was a writer and he asked if there was anyone I wanted to write about for his magazine Interview.

He said they needed something for the January issue. ‘“We want someone young and really new – what have you seen on Broadway, who can you think of” on and on, I was completely stuck. Ludicrously I suggested Mr [Edward] Gorey. Andy said, “Oh come on. He’s creepy – he’s really old. I saw him walking along Park Avenue the other day. He’s too peculiar for me.” That made me laugh. “Too peculiar for you? He’s just a bit moldy. I was obsessed with him for about two years.” Mr Gorey’s star was pretty dim that night.’

I suggested other writers, photographers, film-makers whose work I admired. All too old, too peculiar. Finally, I proposed the choreographer Andy de Groat, who had just collaborated on Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach.

Andy agreed, ‘though he thought Einstein on the Beach was “stinky”. He wanted some more people. I told him I’d provide some later. Andy said to call A de G tomorrow, and then him. “The piece has to be in really soon.”’

Andy’s description of the evening, published in his Diaries, accords with mine, but he added a nice coda. ‘The Eberstadt daughter didn’t say anything during dinner but then she finally blurted out that she used to go to Union Square and stare up at the Factory, so that was thrilling to hear from this beautiful girl. I told her she should come down and do interviews for Interview and she said, “Good! I need the money.” Isn’t that a great line? I mean, here Freddy’s father died and left him a whole stock brokerage company.’

As a kid, I used to feel this need to be outside in the dark, looking up at lighted windows, imagining the life inside. I still do. But nowadays the lighted window is my own, my husband and children are inside, but something broken and uncured keeps me outside, sniffing the night wind and rain, unable to join the circle by the fire.

The Andy I was drawn to was dogged by this same self-imposed and unassuageable loneliness, though his version of the family fire was the VIP lounge at Studio 54 with Truman Capote, Halston and Liza Minnelli. Yet no matter how famous he became, he was still the ‘embarrassing little creep’ who, when he first arrived in New York, had harassed Truman Capote with daily fan letters, phone calls, and camped out on his doorstep; he was still the balding twenty-something sitting every day at the counter of Chock full o’Nuts, eating the same cream-cheese sandwich on date-nut bread; someone who founded his art on boredom, repetition, because only unvarying sameness could soothe his raging anxiety.

I told Andy the first time we met that this was something we had in common – that although, as he put it in his Diaries, I was a ‘beautiful girl’, a banker’s granddaughter, I was also a freak like him, a person who in some way would rather stand outside staring up at the Factory windows than be invited in.

Even today, it’s this same dividedness in Andy that gives me a pang of fellow feeling, the same compulsion to hide away that overrules your hunger to belong, a compulsion that then leaves you feeling too lonely, too weird, too left out of everyone else’s fun. And why does the loneliness feel truer, more essential than any love or acclaim?

By mid-December, I was heading down to Union Square every day after school to transcribe my tape-recorded interview with Andy de Groat. I would install myself at the front desk of Andy Warhol Enterprises, play back a couple of sentences, and type them up two-fingered, dragging out the process tortoise-slow. My pretext was that I didn’t have a working typewriter at home, but in truth the Factory had become my happy place.

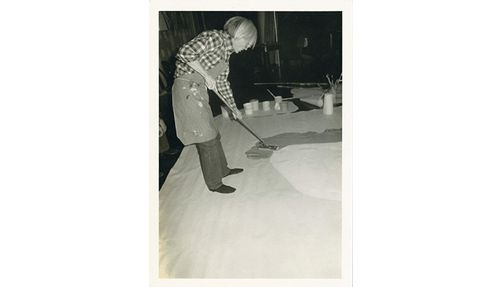

My favorite moment was at the end of the day when Andy put on his apron, picked up a broom, and swept the floor clean – I liked the monastic discipline, the humility of the act. If I got lucky, I would then share a ride uptown with either him or his business manager Fred Hughes, the enigmatic Texan dandy who was the one I actually had a crush on.

One night, Andy and I were sitting in the back of a yellow cab hurtling through the sooty entrails of the Pan Am Building and out onto Park Avenue.

We were discussing our evening plans – in my case, studying for a Russian history test with my friend Martine; in Andy’s case, a dinner party given by Fereydoun Hoveyda, the Iranian Ambassador to the UN who had been the conduit for Andy’s portraits of the Shah and his family. (This was two years before the Revolution, which the ambassador survived, although his brother, the Prime Minister, was executed by firing squad.)

On these taxi rides, I became familiar with Andy’s conversational technique, how he negotiated his mix of shyness, curiosity, malice. He was a persistent questioner, and what he wanted to hear was the most shameful thing about whomever it was we both knew, and because I wanted to please him, I inevitably divulged some incriminating tidbit and his reaction was always, ‘Oh come on. Really???’

I was used to this kind of inquisition from my mother, though she never feigned disbelief, and as with her, I ended up cursing my inability to keep my mouth shut. Andy knew all about mother–child oversharing; his mother lived with him for years and coauthored his first art books, and my guess was that he inherited his malice from her, it was his mother tongue, although it coexisted with a certain vestigial innocence: a part of him that was stuck at an age between child and cat, that wanted to timidly lick the boy he loved all over.

6 January 1977.

I was home sick in bed; I was often sick in bed growing up.

Catherine Guinness, Andy’s assistant, phoned to discuss a photograph to go with the de Groat piece. They had decided that Robert Mapplethorpe should take the picture.

I asked after Andy.

‘Andy’s busy sweeping up cigarette butts.’ She put him on the phone.

I heard the mechanical-man voice with its campy singsong intonations, teasing, a little flirty, and my heart leapt.

AW: Gee, it’s really too bad you’re sick. How did you get it? Who have you been carrying on with?

Me: No one – it’s really disappointing.

AW: Well, are you typing and typing away?

Me: I’m in bed all day. My mother has to read aloud to me.

AW: Did you get nice presents for Christmas? Did you get what you wanted?

Me: Well, not really. Will you get me what I want for Christmas?

AW: Oh I meant to get you a Christmas present but I never got around to it.

Me: Yes, I was so jealous when you gave Mummy something and not me.

AW: Oh were you? Well, I’ll get you something. When are you coming to the Factory next? I’ll give you a present when I see you at the Factory.

I was a resourceful kid; all winter and spring, I produced a steady enough stream of interviews to keep me coming down to Union Square with pieces to transcribe. One day Chris Hemphill, the office assistant, had good news for me: their receptionist was going on maternity leave in June.

As soon as school let out, I started my summer job at Andy Warhol Enterprises. The mid to late 1970s marked a low point both in Andy’s reputation and his creative output, and in those days the Factory’s chief business seemed to be managing the Warhol brand: racking up corporate sponsorships; drumming up advertisements for Interview; above all, getting portraits commissioned. I too was inducted into the hustle – how many of my parents’ rich friends could I persuade to commission a silkscreen portrait? If I succeeded, I would get 25 percent of the price, which I noted as being $25,000. (‘Good! I need the money.’)

Despite the corporate veneer, the atmosphere at the Factory was one of slapstick merriment. That I answered the phone in an inaudible mumble and couldn’t switch from one call to another without cutting off both parties made me the dream receptionist. Andy, Fred, and Catherine all took turns imitating my telephone voice; callers wanted to know if I was still asleep in bed.

In a TV interview from the same period, a reporter accused Andy of being ‘commercial’.

‘I’m a commercial person,’ Andy conceded testily.

‘Why?’

He considered. ‘Well, got a lotta mouths to feed. Gotta bring home the bacon.’ His tone was curt, he was sick of this criticism, of never being taken as seriously as peers such as Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns.

But his answer also reflected his image of himself as ‘Pop’ in the sense of someone who was running a mom-and-pop store with no mom to help out, a single father who needed to keep his feckless kids in line.

If he weren’t there with his apron and broom, we would drown in cigarette butts.

Every morning, I was supposed to be in by nine, in time to answer the phone when Andy called from home to check that all the slackers on his payroll were in the office.

Vincent? Fred? Ronnie? Chris? Everyone was present, though some were looking a little ragged: Ronnie Cutrone had got locked out of his apartment the night before and had to shack up with an ex-girlfriend; Fred Hughes had a black eye. ‘I got into a fight with someone who said Andy was queer,’ he told me, and I believed him; the next inquirers were told respectively, ‘Nenna [my nickname] hit me’, ‘Andy hit me’, and ‘It’s supposed to be punk – that’s a fad that’s so new not even Nenna knows about it’. In fact, Fred’s tendency to fall down stairs turned out to be an early sign of the multiple sclerosis that would kill him at fifty-seven.

Andy came in later, just in time to hide before the first guests arrived. Even on his own turf he was awkward, and gave the impression, I noted in my diary, ‘of hanging around people, rather than the other way around’.

At noon I used to go to Brownie’s, the health-food store around the corner, to pick up a stack of avocado and tuna sandwiches for lunch. There were always visiting rock stars, Hollywood directors, European princesses. A lotta mouths to feed. In the afternoons, Victor Hugo, Halston’s Venezuelan boyfriend, usually showed up with models he’d scouted in gay bars and baths. Andy and his assistants disappeared into the back of the Factory – an area that was tacitly out of bounds to me. This was where Andy made his ‘Landscapes’ – Polaroids of naked men posing and having sex that were then turned into prints and silkscreens.

There was an effort to keep me sheltered from the nude photo shoots, although the finished canvases were sometimes propped against my desk for Victor’s inspection, with much joking about ‘King Kong unclothed’. I looked elsewhere while they estimated cock size. How would I know and why would I care whether this particular specimen was XXL or XXXL?

After work, Andy and his crew, me included, went on to fashion shows, tennis matches, movie premieres, dinner parties, winding up at Studio 54 or Xenon. But even when I got home at 3 or 4 a.m., I still sat down and recorded the previous day in my diary.

All summer I was soaring on a wave of adrenaline, drugs, alcohol and teen hormones. But there were times when I crashed, needed to reassure myself that ‘this is just the trashy segment of a very real life’. At such moments, I found myself increasingly drawn to Andy, whose presence – in contrast to my mother’s experience of him ten years earlier – felt mild, steadying.

Towards the middle of July, something changed. There are holes in my diary – events so disturbing I could only allude to their aftermath. There was the weekend when I was supposedly staying with a school friend in Southampton, but I persuaded this really sleazy fashion designer to hire a speedboat and zip me out to Andy’s compound on Montauk – an escapade that was relayed back to my parents by a journalist.

When my parents and Andy next met – on board a chartered bus to a soccer match of the New York Cosmos, a team founded by Atlantic Records mogul Ahmet Ertegun and his brother Nesuhi – my father yelled at Andy. Andy accidentally called him ‘Mr Eberstadt’, and my parents realized then that some border had been crossed of who was friends with whom.

Was Andy really Pop, the boss who had a lotta mouths to feed, or was he a child still frightened of other people’s fathers?

I too had a scare. My father threatened to yank me from the Factory and only agreed to let me keep working there on condition that I was home every evening by 8 p.m. Though I wasn’t cured of my thrill-seeking, the curfew gave me a welcome breather.

And weirdly it was this blow-up, in which Andy had been humiliated and made to suffer for my misbehavior, that altered our relationship, deepening it into something more intimate, more fusional.

Our morning phone calls were now long-drawn; telephone-friendship was freer, unencumbered by the embarrassment of bodies. We slipped into a comfortable routine: as soon as I got into the office, after watering the plants, I dialed up astrologer Jeane Dixon to hear everybody’s horoscope, and when Andy phoned, I relayed his fortune for the day. Hello Leo, I intoned in Dixon’s rich cheery voice, and Andy feigned either excitement or alarm. Was an old rival really going to make trouble for him? That was so rotten! Who could that be? Was today really the right day for important financial decisions? Did that mean he should be asking for more money for the Toyota endorsement?

Andy told me what he’d been up to that morning: he was in his kitchen making marmalade. This particular batch was too runny, it hadn’t really jelled. He complained about his boyfriend Jed, whose mother and sister he found tacky. He hated the way Jed behaved when his family was around.

He asked about the boys I’d been seeing. Was Michael behaving himself? What about Fred? A sharp plaintive note entered his voice, the bite of jealousy, of feeling left out.

We floated in this disembodied, homey place, thick with orange rind. The intimacy depended on the illusion that I would always be there, although we both knew I was leaving in August.