John Keats and Fanny Brawne had an almost modern typical romance. They met through friends, their first encounter being at the literary Dilke family’s home at Wentworth Place in November 1818. They didn’t fall in love right away. They circled each other with uncertainty a bit at first, and gave each other mixed reviews.

"His conversation was in the highest degree interesting and his spirits good, excepting at moments when anxiety regarding his brother's health dejected them,” Fanny Brawne, willing to be generous about John Keats’ awkward first impression, wrote of him.

“Her shape is very graceful and so are her movements—her Arms are good, her hands badish—her feet tolerable—she is not seventeen—but she is ignorant—monstrous in her behaviour flying out in all directions, calling people such names—that I was forced lately to make use of the term Minx—this is I think not from any innate vice but from a penchant she has for acting stylishly. I am however tired of such style and shall decline any more of it,” John Keats, intimidated by Fanny Brawne’s self-confidence, wrote less favourably of her.

Theirs was to be one of the most tender and tragic love stories of the Romantic Age. English poet John Keats (1795-1821) had twenty-five years on Earth to distinguish himself as a writer, and distinguish himself he did. His legendary repertoire includes stapes of university syllabuses such as his 1819 major odes, which solidified his reputation. And then there is his sonnet “Bright Star,” arguably his era’s greatest tribute to the endurance of devoted love.

“Bright Star! would I were stedfast as thou art —

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night,

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature's patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth's human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen masque

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors.”

The charming and intelligent Fanny Brawne (1800-1865) was the poem’s recipient, and the poet’s muse. She and Keats grew on each other once they’d gotten their initial criticisms out of the way, and fell passionately in love. Brawne wasn’t Keats’s first relationship—his former paramour was Isabella Jones, the inspiration for “The Eve of St. Agnes”—but she was his most serious.

They shared a love of literature and the natural world, and bonded through their romantic sensibilities. He thought her preoccupation with fashion was frivolous, but eventually accepted her love of elegant, feminine clothes as her chosen creative outlet. He also didn’t share her love of dancing, and was jealous when her nervous family and friends urged her to attend parties and balls full of eligible officers, hoping to steer her towards a more financially solvent suitor.

Keats, despite his talents and other likeable qualities, was poor, unemployed, ill from the curse of tuberculosis that plagued his family, and unlucky. His steady publications were failing to make a profit. Poetry, in his time, did not pay out, nor did it pass as a career.

All efforts to sever the connection between Keats and Brawne were for naught. They were a challenge to keep apart, as for economic reasons the Brawne family had to move into the second half of Wentworth Place, Keats' homebase, allowing Keats and Brawne ample opportunities to see each other and seal their union.

The approval of Fanny’s mother for an official engagement was needed for legal reasons, but she withheld it on the basis of Keats’s lack of a steady income to support a wife. Mrs. Brawne was a practical and prudent woman, though not unsympathetic to her daughter’s feelings or situation. She, out of affection for her daughter and Keats, eventually gave her blessing.

Keats and Brawne’s relationship stands out among their contemporaries for its pure, unconsummated status. The other great British-Romantic poets, who enjoyed better health and far more flexible moral codes than Keats, had no qualms whatsoever about sexually consorting with their female love interests and putting them in precarious positions in a strict society. Percy Bysshe Shelley whisked the teenage Mary Shelley off to the continent and impregnated her multiple times out of wedlock. Lord Byron scattered his “affections” across Europe, infamously driving one lover—this was the unfortunate and unstable Lady Caroline Lamb—to madness by enjoying her and then discarding her after only a few months.

Keats does no such thing with his Fanny Brawne. Their relationship was, according to all reports, never physical, and was increasingly conducted through letters and notes as Keats’s health continued to decline and he had to be quarantined to protect his loved ones from contagion. To ease his troubled mind, Brawne would walk by his window, so he could see her and feel reassured of her fidelity.

Brawne didn’t accompany Keats when he travelled to hotter, dryer Italy in 1820 in one desperate, last-ditch attempt to recover his strength and conquer his consumption. As they were only engaged, and not yet married, going abroad together would have been considered improper and soiled Brawne’s reputation. So at home, she waited, and clung to a small sliver of hope. But their separation would prove to be eternal. At the young age of 25, John Keats succumbed to his deadly disease in Rome on February 23rd, 1821, far away from his fiancée.

After the death of Keats, Fanny expressed her deep sorrow through her appearance as Keats expressed his deep love through his poetry. Taking on the persona of his widow, though they were never married, Brawne sheared her hair and dressed herself entirely in black clothing, carrying herself for years as the forlorn phantom of a love that died too early. She did eventually marry a man named Louis Lindo, but only in 1833, over a decade after Keats’s passing.

She had mourned her poet for twelve years, and never fully forgot him. His love letters to her have survived, but her letters to him didn’t. But from the evidence shown in her heartfelt and sisterly letters to Keats’s sister, also named Fanny, it was far from a one-sided love. It was true love. She, his Bright Star, was the light of his life.

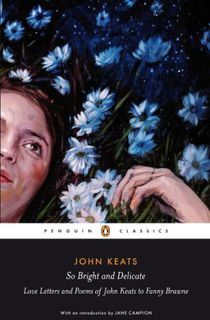

So Bright and Delicate: Love Letters and Poems of John Keats to Fanny Brawne

Featured image: Fanny Brawne via Public Domain, John Keats via Public Domain