Have you ever been so engrossed in a game that time passes and suddenly the day is gone?

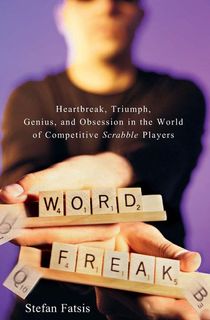

Former Wall Street Journal sports writer Stefan Fatsis knows the feeling. In his book Word Freak, he recounts his rise through the world of competitive Scrabble. Combining linguistics, psychology, and mathematics, Fatsis was instantly drawn into the sport. Below, he recounts the time he faced the number one player in North America: David Gibson.

I played in a 14-game tournament in Charlottesville. And, for the first time, I sat across the table from the No.1 player in North America, two-time national champ and all-time legend David Gibson. Why for the first time? Because I’ve only been in the same tournament as Gibson at the nationals, and I’ve always played in the second division, where I’m less likely to get curb-stomped over and over by superior players.

Gibson is a humble, generous, soft-spoken math professor from South Carolina. When he won the biggest prize in Scrabble history, a $50,000 pot in the 1995 Superstars tournament, he shared his winnings with the other competitors.

That event was chronicled by S..L. Price in his classic story for Sports Illustrated, which was responsible in a big way for my playing and writing about the game.

“I always did poorly in the SAT verbal,” Gibson told Price. “But about 10 years ago a supernatural love for words came upon me. When you get changed, you can’t help it. It’s spiritual.”

Scrabble greatness, like a lot of greatnesses, requires supernatural love and preternatural ability. And unnatural devotion, because the greats memorize every acceptable word. Gibson studied countless flash cards made by his wife. He also annotated his copy of the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary. Here’s what it looks like.

Gibson studied words an average of four hours a day, every day, for twelve years.

When I wrote Word Freak, Gibson was on a six-year Scrabble hiatus. He had conquered the game and needed a break from the pressure, the studying, the expectations. He wanted to do something different. He wrote country music.

But he came back, because it’s hard to stay away. Gibson plays in a handful of weekend tournaments every year and the national championship every few years. It’s too stressful to do it annually, he told me over the weekend. In his last four nationals, Gibson has finished second, third, second and, in 2016, first. He was 65 years old and it had been 22 years since his first title.

Over his career, Gibson has won 75 percent of 1,750 tournament games. He’s averaged more than 430 points per game and won more than $175,000. Before last weekend, his rating was the highest it’s ever been.

So I’m super excited to face Gibson in Charlottesville. He’s 5-0 and I’m a very happy 4-1. I open with IVY, placing the I on the star. He plays PRY to my Y. I hold AAEMR and both blanks. I instantly realize I’m about to take a healthy lead on David freaking Gibson.

But first I need to find a bingo. I look for a “double-double” covering two double-word score squares, by ending a word with -ST or -SE, making SPRY. There’s nothing.

Then I look for an eight-letter word starting or ending on a triple-word square—so a word beginning or ending with the I in IVY.

There are only two playable words, and somehow I see one of them: AMARETTI, the delicious almond macaroons, making the blanks the two T’s for 77 points. (The other word, I learn later, is MARAVEDI, “a former coin of Spain.”)

After a couple more turns, I’m ahead by almost 100. But Gibson plays LIAISES for 71 and then DIETERS for 76, making four words alongside AMARETTI: DE, IT, ET and TIVY (an adverb meaning “with great speed”). Gorgeous. Gibson takes the lead, 178-156.

But I hang close and, after hooking a T to COL and playing THANE for 42, I’m up 268-252. Gibson replies with OX for 42. I play JUDGED for 36 and lead 304-294.

Then, with the tiles dwindling, Gibson played EUDEMONS (“a good spirit”) on a triple-word score lane for 92. Down 386-304, I figure that’s it. But I have the Z and play AZON for 39 and then ILK for 33. With just two tiles in the bag, I trail 416-376.

I hold the letters INOORTT. I spot TORTONI, which doesn’t play. But the A in AMARETTI is wide open. My only chance is if, based on the tiles unseen to him, Gibson doesn’t deduce the possible bingo there and block the spot.

Gibson plays HAEN (past participle of HAE, a Scottish variant of “have”) in a different place for 28 points and draws the final two tiles. And I excitedly lay down ROTATION for 59 through the A to end the game.

Gibson is still ahead, 444-435. In competitive Scrabble, the player who empties his rack first gets double the value of the letters on his opponent’s rack. Gibson holds EIFNR. That’s eight points times two. I win, 451-444.

Gibson congratulates me and we replay the final turns to evaluate what happened. He diagnoses possible mistakes in his two final plays. They totaled 58 points but allowed the possibility of a comeback bingo.

Gibson couldn’t be more gracious. He’s used to blind squirrels like me occasionally finding a nut against him. He knows it’s a thrill for opponents to beat him. (I can relate. It’s fun to beat the author too.) And that, in Scrabble, luck matters.

The next day we face off again, this time with the tournament on the line. Gibson has a 9-3 record, I’m 8-4. Because I haven’t studied like Gibson, I miss a bingo on my opening turn, PLEXORS (“a small, hammer-like medical instrument”), and proceed to stink up the board. Gibson plays a precise, defensive game and wins easily, 446-316. Gibson goes on to win the tournament, of course. (I finish 8-6.) I say that it was an honor to finally get to play him. “I meant to tell you,” he replies, “AMARETTI was a really nice find.”

P.S. I'm totally framing the result slip from my win.

Featured image: Wikipedia