I first read Anne Sexton’s poetry my junior year of high school. My English teacher assigned us each to write a paper on a different American poet—and Sylvia Plath was already taken. This was disappointing since I already worshipped at the altar of Plath, patron saint of melancholic, misunderstood 16-year-old girls with dog-eared copies of The Bell Jar and tear-stained notebooks filled with maudlin poetry that would never see the light of day on their nightstands. But after reading Sexton’s poems, I was ready to convert.

Biographically, Sexton and Plath have much in common. Both grew up in the greater Boston area, struggled with depression, and ultimately took their own lives. Both wrote confessional poetry about the agonies of madness and the experience of being a woman—exploring the physicality of the body and its functions as few poets had before.

The two met in a seminar taught by fellow poet Robert Lowell. They shared their work and discussed past suicide attempts over martinis. After Plath committed suicide in 1963 (Sexton would follow 11 years later), Sexton wrote the poem “Sylvia’s Death,” eulogizing her friend and lamenting her own inability to commit to “the death I wanted so badly and for so long.”

Anne spent much of her childhood in Boston and briefly modelled for Boston's Hart Agency before taking up poetry.

Plath and Sexton’s poems are similar—and can be read in conversation with each other—and yet as I read Sexton I was struck by the undercurrent of humor, the knowing and sly smile, that seeped through her lines. Dark and depressing as they often are, Sexton’s poems can also be genuinely funny—as if to say that yes, life could be hell and it sucked being a woman forced to mask her true feelings behind the oppressive patina of the mid-20th century cult of June Cleaver domesticity, but wasn’t the absurdity of it all something we could laugh about?

This is true most of all in Transformation, Sexton’s collection of twisted fairy tales that undermine our expectations of beautiful princesses, heroic knights, and happily-ever-after endings. She reimagines peaceful Sleeping Beauty as an insomniac who cannot sleep “without the court chemist mixing her some knock-out drops,” and Rapunzel as a lesbian living in her tower with her older, witchy lover by choice, not under duress as the prince who comes to rescue her imagines—the prince who disgusts Rapunzel with “moss on his legs” and “voice as deep as a dog.” Besides poking fun at gender norms, Sexton’s humor highlights the irrationality of these timeworn tropes—bringing our attention to something deadly serious.

Returning to Sexton’s poetry more than a decade later, I feel as if I’m reading excerpts from my teenage diary. Sexton’s words captured my feelings—isolation, sadness, budding feminism, and disillusionment—more articulately and poetically than I ever could. That sense of intimacy and communion with my younger self has the potential to be tinged by embarrassment, as reading one’s teenage diary usually is. But, because of the acerbic wit and subtle irony with which she addresses her subjects, these poems are still relatable where many one-note, nakedly earnest expressions of adolescent emotion are not.

The poem I chose to focus my paper on—“Her Kind”—feels especially resonant today. A short poem, each of its three stanzas addresses one of the narrowly defined roles society expects for a woman—a “possessed witch” doomed to spinsterdom, a doting mother and homemaker, or a sexualized object of public shame. Sexton closes each stanza with the line “I have been her kind,” reinforcing that all women live complex, multifaceted existences that cannot be reduced to type.

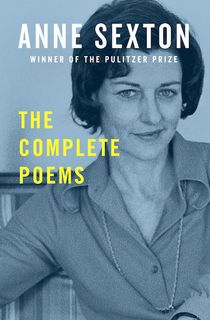

Anne won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967 for her collection "Live or Die."

A favorite book of mine, Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, hit upon a similar nerve. The narrator of the novel, a writer, imagines herself as “an art monster,” a lone creative genius, usually male, who cannot be bothered with the mundane and domestic matters stereotypically considered women’s work. As she goes on to get married and have a daughter, the failed ambition of the “art monster” looms over her much as I imagine Sexton felt herself torn between being a “possessed witch” of a poet and a mother to her two daughters.

Along with other work by contemporary female authors (Elisa Albert’s After Birth comes to mind), Offill’s novel suggests that the conversation of gender roles put forth in “Her Kind,” is not—nor will probably ever be—finished. And because Anne Sexton speaks the language of this conversation with such expertise—addressing its nuances, ambiguities, and focus on individual experience—it’s one in which she’ll always have an important voice.

Discover (or rediscover) Anne's poetry by downloading The Complete Poems.

All images are from the collection A Self-Portrait in Letters.