They first met as teenagers at a youth dance in Stolpce, Poland. Jack always had his eyes on Rochelle. It was a brief encounter and Rochelle was unimpressed with his inability to dance. Jack thought he’ll never meet her again, not after they both faced the horrors of ghettotization, forced labor, and mass killings that decimated their families in the ensuing years.

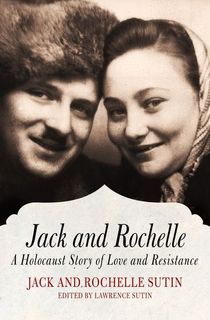

In the excerpt below from Lawrence Sutin’s Jack and Rochelle: A Holocaust Story of Love and Resistance, the pair are reunited again after both separately fleeing from the Jewish ghettos during the onset of Nazi-occupied Poland.

The entrance to the bunker, which took up one of its sides, was a sloping passageway that you went down like a children’s slide. Only one person at a time could slide in or climb out. On two of the sides within there were sleeping bunks made out of saplings and branches. They weren’t comfortable, but they kept our bodies from touching the cold earth directly. On one of the sleeping sides there was also a food-storage area. We ate what we could scavenge and what would keep in those underground conditions—mainly flour, potatoes, and roots.

The fourth and final side was reserved as a cooking area. We made a tiny hole in the over of our shelter, to which we rigged up a piece of metal pipe we had scavenged. It served as a chimney for the little fire we kept going through the nights in a small brick fire pit we had set up in the center of the bunker. We used the fire both for cooking and for warmth, though we were always cold, given what little clothing we had. We had managed to take some blankets from the farms, but they weren’t enough to keep the winter from sinking into our bones. And the fire was for nighttime only—because during the day, especially in the winter sky, any smoke could be clearly seen for a mile or more. At night, under cover of the dark, we could only hope that the farmers would be sleeping.

Our schedule was to start cooking at two A.M., eat in the middle of the night, and sleep during the day. We set a pail on top of the bricks of our firepit, and in this pail we would cook our staple main dish. Here was the recipe:

We started with water. Next to our firepit we dug a deeper hole that served as a kind of well into which the underground swamp water would seep. It did not take much digging to strike water—brackish water, brown like strong beer. And it stank of the swamp. We would drink it through pieces of rag. And on the other side of the rag, as we drank, things would be crawling. It was unbelievable at first, to live this way. If on a particular night we could use melted snow instead of the strained swamp water, it was a gourmet dish! When the water came to a boil we poured some flour in it, so that it came to look like thick clay. That was it—our basic soup, a clay to eat with spoons we had stolen from the farms. We didn’t even have salt for seasoning. We called the soup zacierke. For a different dish with the same ingredients, we would replace the pail with a flat piece of scrap metal and then pour the flour-water clay into little patties that we baked on both sides. That was our bread. Now and then we boiled a big pailful of potatoes.

We couldn’t relieve ourselves outside, because any farmers passing through the woods would have noticed the human waste. So we dug a second hole alongside of our bunker, and dug a small window opening between the two. Then we would relieve ourselves in small pots and empty the pots into that second hole through the window, which we stopped up with rags when it was not in use. That was our toilet-flushing system.

We didn’t dare go outside unless there was a big snowstorm. Our tracks would disappear right away if the snowfall was heavy enough. We could take walks, make expeditions for food. But if the snowfalls didn’t come, we could be trapped inside the bunker for days on end. Naturally, that meant the numbers of visits we could pay to neighboring farms was dramatically reduced, and our diet suffered as a result. Still, there were times, even when the snow was not falling, that we had to go out and get ourselves food from the farms. We had to worry about tracks, about being followed. Our hiding place never felt fully secure. We just hoped that we would not be trapped inside by a surprise ambush, without the chance to wage a fight.

So during this winter of 1942–43, we basically lived like squirrels, hiding in a hole. As you can imagine, the air in the bunker stank like hell. On nights when it was snowing or otherwise very dark, we would lift open the cover of the bunker a bit. Otherwise, we would sit in our hole.

We were doing our best to survive, even to resist, but no one in our group expected to come out alive from that hell. The main thing was not to be taken alive by the Germans, not to submit to their questions, their torture, and a passive death at their hands. We were always armed and had an understanding that if we were ambushed, we would fight until we were killed. If need be, we would shoot one another rather than be captured. It was inevitable that we would die—but death would come on our terms.

Once I became used to that idea, I became extremely brave. I don’t say this to boast, but only to describe the state of mind I was in. I wasn’t afraid of death any longer. I established myself as the leader of the group and always went out on food raids from the farmers in the region. I took huge risks. I would pick farms that were owned by Nazi sympathizers and were situated only two miles from German police headquarters. We would break into the houses and steal lots of food and clothing. Then we would smash the windows and the “the furniture. We killed their dogs when they bit us.

It came to the point that the Germans already knew me by name. I found out from some of the farmers that the German police had placed a price on my head! This was an honor at a time when Jewish life came very cheap.

Want to keep reading? Download Jack and Rochelle today.