There are plenty of topics that until very recently have been deemed “unsuitable” and “unacceptable” for public literature. These topics tend to fall under the same category of conversation starters banned from the table at a formal dinner party: bodily functions, sexuality, poverty, illness, addiction, racist and domestic violence, and most especially foul language that might have come straight from a city’s most dangerous streets and alleyways.

And yet a major cultural shift from the mid-twentieth century and onward led to prominent North American authors abandoning all pretense and embracing these subjects as the core elements of their output. They did this while somehow—and here one can only be impressed—managing to secure reputations as highbrow writers.

The term “dirty realism” itself was coined by American author and social critic Bill Buford, who studied the movement closely and considered the phrase the only appropriate title for this onslaught of books where these shameless semi-autobiographical authors recorded thinly disguised accounts of lower-class drinking, skirmishes, carnal practices, abuse of money, and anything else they have decided no longer embarrasses them (or perhaps never embarrassed them in the first place). Here are four books by authors who invite their readers to get their own hands dirty, at their own risk.

Heart Is A Lonely Hunter

Unsurprisingly, the genre of dirty realism is considered something of a boys’ club, and credit should be duly given to Carson McCullers for being a woman writer in the 1940s who dared to reject being traditionally romantic in favor of being brutally honest.

In her debut work The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, a deaf-mute engraver living in a 1930s mill town has three companions who rely on him to be their free counsellor and audience for their bitter rants: a Black socialist physician alienated from his family; an alcoholic jack-of-all-trades whose tirades for workers’ rights quite literally fall on deaf ears; and a depressed teenager whose grand ambitions are thwarted by her family’s relentless generational poverty.

Yet despite being so well-liked and sought out, the deaf-mute engraver, lonely and silently aching, yearns only for the companionship of a close friend who was carted off to an insane asylum. These deeply troubled characters’ lives and struggles intertwine to create one of the staples of Southern Gothic fiction, which modern scholars have also identified as dirty realism for its unabashed depiction of Great Depression experiences that are not necessarily triumphant against the odds or diluted for readers’ comfort levels.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

This title is unique on the list for being a collection of short stories rather than a novel, as Raymond Carver had much more than one dirty tale to tell. An alcoholic sells off his pathetic possessions, inviting the disgust and pity of his more prosperous customers. A couple running a seedy motel have to come to terms with the end of their marriage. A narrator accepts a photograph and an offer of friendship from their own stalker. A woman throws her husband out of the house after he threatens the lives of herself and her teenage daughter with a smashed pickle jar. And the collection’s title story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” is a long, shocking, eye-opening conversation held over two bottles of hard gin.

These are just some of the episodes that make up the collection which sealed Raymond Carver’s reputation as a fearless revolutionary for the American short story, which up until his introduction was still in its rather shy adolescence. The theme of the collection is consistent: everybody is desperately distressed and on the verge of a breakdown, and personal disaster is a few well-crafted sentences away.

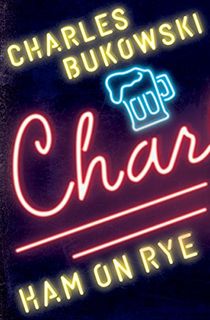

Ham On Rye

Charles Bukowski is considered the unrivaled king of the dirty realism genre, and Ham on Rye is his royal sceptre. His fictional stand-in, Henry Chinaski, is so obviously Bukowski’s own alter-ego that this book might as well be labelled a memoir.

Between the years 1920 and 1941 Henry Chinaski grows up in Los Angelos in a poor, abusive family that certainly does not represent the location’s reputation for wealth, success, and glorious happiness. At one point, the young protagonist and his starving family are chased out of an orange grove for attempting to steal fruit, despite Los Angeles being abundant with orange trees.

As the book goes on, readers are treated to detailed scenes of Henry as an awkward adolescent discovering the free pleasure of masturbation and the not-so-free pleasure of alcohol, another hard to obtain luxury. And yet the novel’s most disturbing events take place on medical grounds as Henry, suffering with painful, chronic acne, is subjected to experimental treatments by unsympathetic doctors who view him as a free, convenient test subject for their malpractices.

Ham on Rye is a testament to the theme of the everlasting power struggle between those with money and those without money. Those with money will always either withhold resources or wreak debilitating havoc on those who don’t. Bukowski understood this and constantly sought to expose it in his fiction.

Blood Meridian, or The Evening Redness in the West

Cormac McCarthy of The Road fame is also a pillar of the dirty realism genre, with several books under his name that do not always make it onto high school syllabuses because they are deemed just a tad too violent to introduce to impressionable teenagers. His Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West is one such book.

Its protagonist, a teenager known to the readers only as “the kid,” represents every vulnerable young person from any era who can be easily absorbed into a radicalized hate group or cult and rendered a danger to society. “The kid,” illiterate, ignorant, and groomed for violence, is taken in as a runaway by the Glanton gang, a cluster of scalp-hunters whose blood sport and profession is slaughtering Indigenous Americans and immigrants for satisfaction and bounty money.

The novel is told in the form of an anti-heroic epic that follows “the kid” from his teenagerhood to his forties, but McCarthy chooses to keep him anonymous, perhaps to remind the readers that this kind of person, stitched so seamlessly into a criminal, could really be anyone. Some readers may continue to prefer the safer route of The Road to this gruesome plot.