Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts to an abstract artist and a light fixture salesman, Fred Waitzkin knew he was going to be a writer by age 13. He'd dabbled in other things, like sales, big game fishing, and Afro Cuban drumming, but between the literary influences of his parents and Ernest Hemingway, it almost made no sense to become anything else.

Waitzkin studied English at Kenyon college, received his master's at NYU, and then taught poetry at the College of the Virgin Islands where he met his wife, Bonnie. After the two settled in New York City, he tried his hand at writing short stories, to no avail, and ended up launching his career by writing feature journalism, personal essays, and reviews for various magazines.

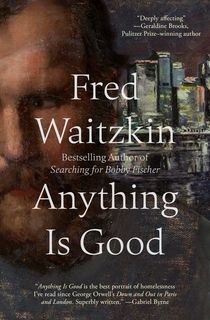

He published Searching for Bobby Fischer, one of his best-known works, in 1984, and has been publishing books ever since. His newest novel, Anything is Good, is a complex and genius portrayal of homelessness inspired by Fred's childhood friend. Waitzkin shares more in our interview with him below.

1. What inspired you to write your newest novel, Anything is Good?

Usually after I finish writing a book, I feel an emptiness that is hard to shake, and I begin to worry there will never be another topic to fully engage me. Ideas fleetingly pass through my mind but nothing that I want to make into a book.

Three years ago this feeling was heightened by the recent loss of my two closest friends. During this period of darkness and loneliness, I began to think about my best friend in high school, Ralph Silverman. Ralph was the smartest kid in our high school and right out of college he began making a reputation as a brilliant philosopher.

I didn’t even know if Ralph was still alive, but I knew that he had been living in a tiny apartment in Ft. Lauderdale. One day I called him on the phone and was relieved to hear his voice and that same throaty laugh I knew so well from sixty-five years earlier when we were bad boys, cutting classes together and sneaking into jazz clubs on weekends.

I asked him to tell me something about the years when he seemed to disappear from the world. In the next months during scores of calls Ralph told me one of the most astonishing stories I’d ever heard, which was the inspiration for my new novel, Anything Is Good.

2. You’ve listed Ernest Hemingway, along with both of your parents, as strong literary influences. How have they shaped your writing?

My parents never should have married. In the sixteen years they were together I never observed a moment of tenderness between them. Mom was an abstract painter, a lover of progressive jazz, a renegade forced to live in Great Neck on Long Island among people she couldn’t relate to.

Dad was a salesman, a remarkably talented one. He sold commercial lighting fixtures for Manhattan office buildings, and in the sixties he established a reputation as a cut-throat negotiator who would do whatever was called for to close a deal.

I worshipped my father who began taking me fishing on weekends and often closed his biggest lighting deals in fancy night clubs. I sometimes went with dad to the Embers where George Shearing played his magical piano and Armando Peraza pounded the conga drums while Dad closed his deals. I wondered if I could ever be like Dad someday, going to the night clubs, smoking Luckies and making big deals.

But it was Mom who introduced me to Hemingway, putting Life Magazine in front of me and ordering me to read his story about an old man battling a 2000-pound marlin. Hemingway’s sentences had rhythm that pulled me inside the same way that Armando Peraza’s rhythms seemed to seal the lighting deals for Abe when we went to the Embers. Over the years in my writing the warring sensibilities of my parents taught me about the tension necessary to build compelling plots and to this day I write my sentences to the beat of the drums.

3. Because of its movie adaptation, you are perhaps best known for your first book, Searching for Bobby Fischer. What made you decide to document your son’s story in that way?

Forty years ago I was writing magazine pieces. In one article for New York Magazine I wrote about park chess hustlers working into the night in Washington Square Park. Some of those guys were high level tournament players looking to make some easy money from patzers. Soon after the story appeared I was contacted by an editor at Random House, Joe Fox.

The afternoon I visited Joe I was nervous as hell. I’d never written a book and Joe Fox was Philip Roth’s and Ralph Ellison’s editor. Joe and I had a nice talk, but he didn’t really seem all that interested in a book about chess hustlers. Then he asked me why I was so interested in chess and I told him that my six-year-old son, Josh, was crazy about the game and often played in Washington Square park against the hustlers and sometimes held his own, that my little boy was much better player than I was.

That’s when Joe said to me, “That’s your book.” I swallowed and nodded, but really I thought he was crazy. Josh was just a little kid. How was I going to write an entire book about a little kid? What if he stopped playing chess in a few months? What would happen to the advance Random House was paying me? This idea felt like a terrible mistake, but that’s how the idea of Searching for Bobby Fischer was born.

4. Your first few books were nonfiction, but over the past 11 years, you’ve been publishing novels—The Dream Merchant, Deep Water Blues, Strange Love, and now Anything Is Good. What sparked the change? Do you see yourself returning to the world of nonfiction?

After graduate school and a couple of years teaching literature at the College of the Virgin Islands on St. Thomas, I felt ready to write my first novel. My mom had a beat-up, cold-water studio on 14th Street across from S Klein’s. She loaned it to me to write my first novel.

I spent a year working there, often with my hi-fi blasting Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane, while I tried to discover the original plot that would put me on the map. I wanted to write something like Anna Karenina. I spent the whole year trying but never wrote any decent pages. I couldn’t think of one original plot. This was devastating. How could I be a novelist without a decent plot?

After this I began writing freelance pieces for national magazines. I wrote about writers, sports figures, adventure stories, personal essays. I always wrote my stories in the first person, which was unusual at the time, but my editors seemed to enjoy my quirky point of view.

Writing nonfiction in the first person where one’s own point of view was always an element in my story was how I began to learn about fiction. I eventually realized that many if not most of the novels that I admired had their roots in true stories.

Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea was born from a true-life event on Cuba that Hemingway had written about in a magazine piece fifteen years before he wrote the novel. Jack Kerouac’s novels might have been called memoirs, as they were based upon stories that took place in his life with his friends.

The realization that my own ‘true” stories were a gateway to fiction opened up the world of fiction to me. Where there had once been no stories, I could now imagine many—many that I had lived myself.

Okay, not so easy as that. I needed to find the right story for Fred, one that I could build upon and bring to a new place and where the plot would interest or intrigue readers.

Will I ever write non-fiction again? Tough question. In my family whenever I begin to tell a story from my life my son and daughter soon begin to laugh. Then one of them says, “That never happened, Dad.” They are always accusing me of making things up.

5. What’s the last book you read that you wanted to tell the world about?

Somehow, over the years I never read Graham Greene, which today amazes me and perhaps says something about mutability. About a month ago at the advice of a friend I began reading Greene, and today I feel like I never want to stop. I’ve read four of his books, and one of them, The Quiet American, three times.

He is an absolutely genius writer, at the level of Hemingway or Faulkner and yet, seventy years since he wrote his masterpiece novels, he’s rarely read and mostly forgotten. My favorite is The Quiet American. Love and war have long been fertile ground for fiction, and in Greene’s novel the delicate and mostly pre-verbal love relationship between Fowler, an older cynical opium-addicted journalist, and Phuong, a twenty-year-old Vietnamese dancer, plays against the gruesome violence of the early days of the Vietnamese war.

Anything Is Good

Despite Ralph Silverman's stark genius, his tendencies to study philosophy, enthusiastically watch foreign films, produce music on the computer, and hold long conversations with his parrot made him an easy victim for bullies. And unfortunately, his adult life wasn't so different.

Though a friend of great scholars and the son of a wealthy (yet shady) businessman, Ralph ends up in South Florida, physically abused, and cast off into homelessness with nothing more than a pair of broken glasses. Anything is Good is the story of a man tormented by the fate of his childhood friend, and the tale of said friend's complex navigation of the ups and downs of homelessness.