In 1963, Mary McCarthy's The Group rocked the literary world with its unapologetic descriptions of female orgasms, birth control, breast feeding and sexual assault. But the book offers much more than just shock value. McCarthy's biting wit and fascinating character studies makes this novel well worth reading more than five decades after it was originally published.

Below, Gloria Steinem explores what made this book so controversial—and why it still resonates with readers today.

The Group, a novel by Mary McCarthy, is about eight women friends who graduated from Vassar in 1933. It was published in 1963, became an irresistible Hollywood movie in 1966, and in the 1990s, inspired Candace Bushnell to write newspaper columns called “Sex and the City” that were collected in a book, and turned into a television series that ran from 1998 to 2004. In between came a 2001 BBC radio series. Then the Sex and the City movie came in 2008, a sequel in 2010, and a third is planned, though the televised story is in syndication worldwide, and is one of the most successful media franchises of all time.

In short, I am not suggesting you read or re-read The Group because it is a neglected novel. There are multiple other reasons.

Mary McCarthy in 1963.

For one thing, many people don’t know that The Group is the birth myth of Sex and the City. If you’re curious for that reason, you will be rewarded by an intelligent and unsentimental novel by McCarthy—a woman I doubt ever wore designer high heels—and I’m betting you will get hooked, read more of her novels, and learn about her own influential group of ferocious intellectuals who debated socialism and other ideas with brilliance and became the advance troops of the Sexual Revolution.

For another thing, The Group and everything that flowed from it are powerful counters to the idea that novels called “chick lit”—because they are by and about women—are not good investments. Not only are women the majority of book-buyers, but in an unbiased world, male-audience books about Wall Street and warfare would be called “prick lit.” Since The Group was made into a movie called a “chick flick,” it also counters the idea that movies by and about women are not good investments.

In truth, anything that has more dialogue than deaths, more emphasis on how we live than how we die, may be called a “chick flick.” Hollywood’s preference for movies full of high-tech chases and gun battles rests mainly on the fact that they can be exported without language problems. Yet dollar for dollar spent on production, so-called “chick flicks” are equally or more profitable than those “prick flicks” seen multiple times by teenage boys.

Finally, I think you will find that the eight women of The Group—condensed into four by the television series—are the reason why this novel and its progeny are still with us. They are Rorschach tests of social change. Each is trying to express her hopes and ambitions within the straitjacket of gender, and each is a unique human being dealing with a need for love and family that, for women, can be more limitation than reward.

In short, The Group lasts because it is read or re-read as an indicator of change—or the lack of it. For instance:

Would Kay still be supporting a creative husband who has too little talent to succeed yet enough to make her feel inferior and to attract other women?

Would Priss, who is humiliated by her obstetrician husband for being unable to carry out his ideal of childbirth, now be a pioneer of birthing centers and midwives?

Though Lakey wouldn’t have to conceal being a lesbian while a student at Vassar, would she still fall in love with a rich, powerful, and not very smart woman who is as dominating as a man?

Would Pokey, the “fat and cheerful New York society girl,” now be suing for an equal share of inherited power? After all, it is still more likely to be left to sons—or even sons-in-law—than to daughters. Would she be talking about the masculinization of wealth? It’s just the other side of the feminization of poverty.

Would androgynous Helena now describe herself as transgender, and become more at home in the world by transitioning into a man? What was not possible in the 1930s is happening in the new millennium, including at Vassar.

Dottie, who famously got a pessary—as diaphragms were then called—would no longer cause the novel to be banned in Ireland, Italy, and Australia, but would she still marry a man she doesn’t love as the path of least resistance?

Libby would no longer be told that book publishing is for men, to marry a publisher rather than be one, but would she still bring no legal charges when she is quietly raped?

As for Polly—probably the alter ego of Mary McCarthy, who also was an outsider by class and a survivor of family problems—she might still be working in a hospital, taking care of a father who is losing his grip on reality. But she would no longer take Freud seriously enough to argue with, nor would the kind psychiatrist she falls in love with.

Altogether, The Group would now be appreciated, not banned, for its demystifying description of female orgasm. We can hope that eight friends would no longer be all white, as were so many classes graduating from Ivy League colleges until the 1960s. On the other hand, I don’t remember media coverage of Sex and the City that asked why—in a city that is more than a third African American, Hispanic, and Asian American—those women friends were all white. I bet Mary McCarthy would have asked. She was very conscious of class and anti-Semitism. Wouldn’t she also have written about Race and the City?

The Group is worth reading and re-reading for all of these current reasons. Women’s lives are better indicators of change—or the lack of it—than any statistic or generality, and the bedrock appeal of this novel, like its television and film progeny, is friendship among women.

Now that we know how and why we need each other, read The Group as a measure of change.

Download Mary McCarthy's The Group today.

About the Author

Gloria Steinem is an American feminist, activist, writer, and editor who has shaped debates on gender, politics, and art since the 1960s. Cofounder of Ms. Magazine and a founding contributor of New York Magazine, Steinem has also published numerous bestselling nonfiction titles. Through activism, lectures, constant traveling as an organizer, and appearances in the media over time, Steinem has worked to address institutional inequalities of sex, race, sexuality, class, and access to power in the United States and abroad.

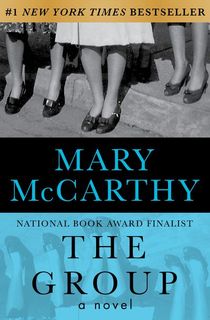

Photos (from top to bottom): U.K. cover of The Group by Mary McCarthy; Mary McCarthy courtesy of Jane Bown