Sixteenth century Florence was home to the Renaissance’s greatest talents—among them, the inimitable Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti. The former was, most famously, the genius behind oils like the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper. The latter, for the Pietà, David, and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

From impoverished upbringings and familial scorn to wartime trauma and failure, both men experienced their share of hardship. And it was these parallels, combined with similarities in their artistic training and style, that pitted them against each other. Their rivalry is one of the greatest artistic feuds in history, though there is only one account that gives us details of a bitter quarrel in the streets of Italy.

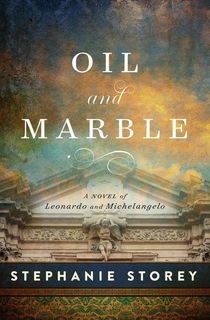

In her stunning novel Oil and Marble, Stephanie Storey imagines the history behind their tumultuous relationship. Michelangelo is a novice in the art world, but eager to make a name for himself. Da Vinci is years older, and already at the peak of his career—all of which are reasons, Storey purports, behind their ongoing animosity. And when Leonardo loses the David commission to Michelangelo years later, it only stokes the fires.

The excerpt below describes the artists' very first meeting. Commissioned to produce an altarpiece, Leonardo has free room and board at a Florence friary—though he’s been working at a slower pace than usual, making excuses that “creating new life [takes] time.” To demonstrate his dedication and progress to the friars, he throws a party in his studio...

Enter a young Michelangelo, in awe of da Vinci’s talent, but with dreams of his own glory. His brashness and shabby appearance earn Leonardo's immediate condescension—and so begins a lifelong rivalry fueled jealousy, ambition, and history’s greatest masterpieces.

Read on for an excerpt to discover how the two legends became enemies, and then download the book.

One of the ugliest men he had ever seen was standing in front of him. The stranger was young, with black hair matted down with grime. A disfigured nose. Wearing the soiled clothes of a peasant who hadn’t washed in weeks, he was bloodied and bruised as though he had recently lost a tavern brawl. He clasped a ragged leather bag of tools and carried a sketchbook in his front pocket. He was an artist, Leonardo surmised, but judging by his meager dress, not a very successful one. Why were all of these uninvited guests disrupting his party this evening?”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Leonardo said, “please welcome a child most certainly made by night.”

The crowd laughed, and the young man blushed, hunching his shoulders and crossing his arms in front of his chest; he appeared as uncomfortable with himself as everyone else was. “Maestro Leonardo, it is an honor to meet you.” He spoke like a boulder clearing the way during a landslide. “I am a sculptor and at your service.”

Well, that explained it; stonecutters were always unkempt. “Sit down and sketch, son. Copying the masters is the best way for a student learn.” Leonardo waved his hand dismissively and returned his attention to the problem at hand. He was going to have to figure out a way to make up the evening to the friars. Perhaps he could invite them in for a private viewing the next day or even attend services that Sunday. He must do something to atone for the notary’s rude interruption.

“May I show you some of my work?” The sculptor fumbled for his sketchbook. “It would be a great honor if you could give me your endorsement.”

Why was this sculptor still bothering him? Yet another Florentine, desperate for the great Leonardo da Vinci’s friendship and approval. What a night. “By all means, young man. Come in, uninvited, to my studio and take me away from my guests. Please, please, allow me to interrupt my night in order to serve the needs of yours. It is apparently the theme of the evening.”

The sculptor looked confused. Did he not understand sarcasm?

A well-dressed gentleman stepped forward. Leonardo recognized this stylish fellow as a local artist, Francesco Granacci. “Maestro,” Granacci said, offering a deep bow. “This is my friend, Michelangelo Buonarroti.”

Florence, Italy

“Buonarroti?” Leonardo muttered. “I have heard of you.”

“Yes, sir?” The sculptor’s eyes widened with childlike hope.

“Salaì, what did we hear?”

“Salaì leaned in and whispered in his ear.

“Yes, yes, of course,” he said. The night was already ruined. Time to have a little fun at the intruder’s expense. “Gather around my friends, to meet a truly legendary artist.” He waved the spectators in closer. “My son, why didn’t you tell me who you were? I heard of your work all the way up in Milan. The whole court spoke of it. Even Duke Sforza.”

The young sculptor flushed. His chin raised a notch. Leonardo recognized the look. It was pride. He was tired of other people’s pride.

“This is one of his generation’s best and brightest,” Leonardo announced. “The famous carver of …” He let his voice trail off, letting the anticipation build. “Snow people!”

The guests giggled as the sculptor’s expression darkened. Granacci grabbed his arm as if to restrain him.

What was the boy going to do, punch him? Go ahead. Leonardo could use a good fight. “You all remember the snowman young Buonarroti made for Piero de Medici, right? I, unfortunately, wasn’t here to see it. Entertain us, my boy, with glorious tales of your days in ice. Was it cold?”

The sculptor’s face drained white as the snow he’d been forced to carve. “So I had one lousy commission. You’ve had your share.”

“Never something quite so laudable as snow art. Congratulations on discovering an art that abandons his maker before his maker can abandon it.”

“Perhaps you’ve heard of my Pietà, currently on display in the Vatican.” He spit the last word as though flinging a knife toward Leonardo’s throat.

“That’s Gobbo’s. From Milan.” Leonardo looked to Salaì, who nodded in agreement.

“No. It isn’t. The Pietà is mine.” He drew himself straighter.

“Poor hunchback, can’t even get a decent credit. Ah well.” Leonardo turned back to his guests. “Who wants to see a magic trick?”

The sculptor’s filthy fingers grabbed his arm.

“Michelangelo, please,” Granacci whispered.

“Tell me, tell us all,” Michelangelo said, raising his voice. “Have you seen my Pietà?”

Leonardo squared his shoulders and turned back around to address the sculptor. “No. The last time I was in Rome I did not have time for visiting inconsequential carvings.”

“Then what have you heard about it?” Michelangelo pressed.

“That your Mary is not a thing found in nature. She is gargantuan …” He puffed out his cheeks and chest and stomped around like a giant. “Three times the size of Jesus and”—he launched his voice high—“twice as young.”

The audience tittered.

“Don’t you know,” Leonardo went on in a mock-scolding tone, “that mothers are smaller and older than their sons? What are schools teaching students these days?”

He led the crowd in a chorus of laughter.

“A chaste woman preserves her youth and beauty,” the sculptor said.

Did Leonardo spot tears in the young man’s eyes? Had he taken the teasing too far? As the older and wiser artist, should he help this young buck preserve his dignity? Leonardo leaned in and whispered, “Pipe it, boy, you’re losing the crowd.” Then he addressed the gallery. “I know. Let’s try to turn tin into gold. The wonders of alchemy.”

“The body is a reflection of the soul; the more moral a person, the more beautiful,” Michelangelo said.

“Thank you for proving I must be more moral than you,” quipped Leonardo.

The guests laughed.

“Listen, son,” Leonardo said, putting a gentle hand on the sculptor’s shoulder. It wasn’t his fault that the notary had ruined the evening. “A drop of ocean water had the ambition to rise high into the air. So, with the help of fire, it rose as vapor, but when it flew so high that the air turned cold, it froze and fell from the sky as rain. The parched soil drank up the little drop and imprisoned it for a long time: punishment for its greedy ambition. You’re like that drop of water suffering from too much ambition. I have not seen your Pietà. I cannot judge it. But I can assure you, just by the looks of you, that you’re not yet a master. So please, sit down and sketch my work. Maybe you’ll learn something.”

“Bastard.” Michelangelo enunciated the word so clearly that no one could doubt what he’d said.

As the crowd murmured, Leonardo took a breath. He had tried to be nice. “Yes, it is true. I’m an illegitimate son. But I am thankful for my illegitimacy.” He stared into the sculptor’s brown eyes. “If I had been born legitimately to a legitimate married couple, with a legitimate father, I would have had to suffer through a legitimate education in legitimate classrooms, memorizing legitimate information made up by legitimate men. Instead I was forced to learn from nature, from my own eyes and my own thoughts and my own experiences, the best teacher of them all. I am, it is true, an unlettered bastard, for shame, but”—he gestured around the room—“does anyone here think that makes me stupid?”

Silence descended. Guests stared into their glasses of wine.

The night had gotten out of his control. It was time to take it back. He grabbed his lyre and hopped up onto a tabletop. “Painters versus sculptors. A long, spirited rivalry. But I believe I have finally found a winner.” He strummed a few chords. “The painter sits before his work, perfectly at ease, moving a light brush dipped in a pretty color. His house is clean, he is well-dressed. But the sculptor”—he pointed toward Michelangelo—“uses brute strength, sweat mixing with marble dust to form a mud, daubed over his face. His back covered in a snowstorm of chips, his house filthy from flecks of stone. If morality is akin to beauty, as this student himself claims, a painter is by definition more moral than a stonecutter.”

Michelangelo’s flattened nose flared, and he opened his mouth to offer a retort. Instead, he turned and bolted from the studio.

“Music,” Leonardo called, and the band began to play once more.

Want to keep reading? Download Oil and Marble to learn the full story.

Photos (from top to bottom): schmid-Arts / Pixabay, april / Pixabay