On December 15, 2021, bell hooks passed away at the age of 69. Born Gloria Jean Watkins, she was known for her many feminist writings, including her nonfiction works All About Love and Ain't I A Woman?

bell hooks wrote about the ways feminism failed to address the needs of all women. Specifically, feminism was often not representative of working-class women and women of color. Today we'd call this the need for intersectional feminism—and though bell hooks didn't use those exact words, much of her writing serves as the foundation for this movement.

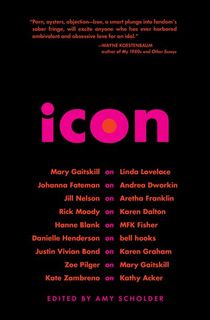

Below is an excerpt from an essay by author and TV writer Danielle Henderson, originally included in a collection of essays called Icon. Henderson writes about growing up poor in the 1980s, the racism she faced from her white classmates, and how bell hooks made her realize these experiences weren't just hers. It's an impact bell hooks had for an entire generation of Black women, and continues to make today.

I learned about race from the outside in, caught in the crosshairs of intolerant, sheltered people, unable to understand why my skin color precluded me from having teachers pay attention to me in class, from making friends, or from having the same hopes for my life that other children had. I didn’t have the language to explain how these childhood experiences shaped my life until half of it was over and I’d already moved far away from Greenwood Lake. I didn’t understand how my own story fit into a larger cultural experience until I read bell hooks.

bell hooks was inaccessible to me in a school system that excluded women and minorities from its history lessons, but I found her when I went to college in 2006 at the age of thirty. A cultural critic, writer, and academic feminist who writes in an approachable, nonacademic way, hooks changed the landscape of feminism when she wrote Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, a book that moved the discussion from empowerment for middle-class white women toward a more inclusive feminism by criticizing the feminist movement for routinely excluding minority voices. She wrote that book when she was still in college and published it in 1984, the same year my classmates were calling me a “nigger.”

Obviously I would not have been able to understand her work in 1984. But when I read the first chapter of Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center I felt like she’d been waiting out there, to help me make sense of my life. Understanding her was crucial to reigniting my feminist identity; finding her at all was a miracle.

Related: 15 Must-Read Feminist Books from the Past 100 Years

Ironically, we read hooks last in my women’s studies class, after the instructor taught us about the legions of historically important white feminists. hooks’s take on liberal individualism and the “one-dimensional perspective on women’s reality” finally put words in the way of my feelings about belonging to a group that didn’t seem to want me as a member:

Like Friedan before them, white women who dominate feminist discourse today rarely question whether or not their perspective on women’s reality is true to the lived experiences of women as a collective group.

hooks wasn’t condemning whiteness, but using her own life as a way to shine a light on the importance of what it means to claim feminism for women who can’t access it in the same way.

It wasn’t until I read bell hooks that I finally learned how to disconnect from the shame I felt about growing up poor. hooks was adept at writing her own life story, her travels from Kentucky kid to professor, tying together her history with that of the larger black cultural history all along the way. My grandparents taught me about the civil rights movement so I thought I knew what it meant to be black. But through hooks, instead of seeing blackness as something that hindered me, I finally learned how my own story fit into the larger cultural context of displacement.

Related: 9 Empowering Books for Women

[...]

After several years, a number of restarts of my life in various cities, I landed in Rhode Island and enrolled in an introduction to women’s studies course. Three weeks later, I was reading bell hooks for a homework assignment.

The professor only assigned one essay from Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, but I went to the library and checked out the entire book. I read it in one sitting. Then I went to the local bookstore and purchased it. I read it again, this time highlighting passages and folding down corners of the pages so frequently that the front cover always rests slightly open. Nothing had ever made as much sense to me. hooks’s insistence that we need a feminist theory that speaks to everyone in order to effect revolutionary change was now the basis of my academic career. When hooks wrote about how systems of power affected the development of a culture rooted in gender equality, it was like she was handing the world a blueprint for ending sexism. And when hooks wrote, “I am suggesting that [black women] have a central role to play in the making of feminist theory and a contribution to offer that is unique and valuable,” I felt all of the validation and hope the riot grrrl movement was never quite able to give me.