Paris is a stunning place to visit, and its sights are unmatched. The Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, the Seine, and the Luxembourg Gardens. Baguettes, croissants, chocolate crêpes. Bicycles, book stalls, brushstrokes on painters’ canvases. There are countless memoirs and novels that laud the City of Lights as the ideal cradle for nurturing artistic talent and the sparkler for igniting passion.

But, Paris has a dark side as well and there are writers who, having dwelled in its shadows, emerged rebellious against upkeeping Paris’s commonly romanticized image. They have a different story to tell, about a very different Paris, and readers must choose whether or not they are ready to accept the fact that Paris also has a murky history underneath its dazzling, distracting glitz. Here are four books that bring to light the dark and haunted underbelly of one of the world’s most adored cities.

Quartet

Jean Rhys lived in Paris as a misplaced woman, and just like any other city, Paris in the first quarter of the twentieth century was not necessarily kind to this particular set of people. Rhys’s debut autobiographical novel Quartet is a beautifully crafted but depressingly honest account of what life was like for an abandoned, penniless woman in 1920s Paris, whose husband was incarcerated for shady art dealing, and whose looks were threatening to fade from poor health. For Rhys’s self-insert protagonist, Marya Zelli, Paris is not the city of romance. It is not the city of dreams. It’s instead a city of excruciating loneliness.

Marya’s daily routine is empty and aimless. She has no purpose in life. She doesn’t fit in with Paris’s thriving art scene. She has lunch in one cheap café, dinner in another café, coffee, and brandy in yet another…and on and on it goes. She goes for long walks through the Parisian streets to fill her time. Being surrounded by beautiful gardens and architecture brings Marya little comfort as she struggles to battle a deep, debilitating depression under these circumstances.

Job opportunities for unskilled, undisciplined women in Paris were few, so Marya turns to prostituting herself. She becomes the kept woman of a well-off benefactor named Heidler, who is married. His wife, the pragmatic Lois, only reluctantly accepts the situation because of the Parisian bohemian culture of “freedom of love” which, unfortunately, does not benefit the conventional spouses of those with power and influence. Both women, mistress, and wife, become trapped in a miserable triangle, with no end in sight unless the second half of the quartet, the men, decide the outcome.

Down and Out in Paris and London

Readers with a rosy vision of Paris in the 1920s as an all-glamourous, never-ending party for everyone can expect to have their bubble violently burst by George Orwell’s disturbing tell-all memoir Down and Out in Paris and London. In his mid-twenties, the ambitious Orwell decided to undertake a risky project: a book about living on the bottom rung in two major metropolitan cities, Paris and then London.

An intrepid reporter by trade, Orwell embarked upon this assignment wholeheartedly. His and the readers’ unfortunate discovery throughout the course of his immersive research campaign is that Paris in the 1920s—the setting for the first half of the book—is only fun when you have the cash to splash. If you were like Orwell and his acquaintances, perpetually unemployed or underemployed, and condemned to living in filthy rented rooms with deranged criminals and addicts as your next-door neighbors, your lifestyle did not in any way resemble F. Scott Fitzgerald’s glittering, champagne-tippling portrait of the Jazz Age, or even Ernest Hemingway’s portrait of Paris in A Moveable Feast as a grand, easily manageable adventure. For the miserably poor, it was a nightmare, and the only splashing done is in a sink or on the floor with a mop, for fourteen to sixteen hours a day.

When George Orwell gets a job as a plongeur, or dishwasher, in a high-end Parisian hotel, the staff are so bitter and underpaid that they regularly steal food from the work kitchens, and at one point a co-worker breaks into his room on his day off to shake him awake and demand that he get out of bed for an enforced extra shift.

At this stage in French history, workers’ rights were virtually non-existent. It is not a coincidence that this is the exact same era and country where the Papin sisters, a pair of abused, overworked French maids, went ballistic and murdered their own employers. Down and Out in Paris and London is not just an autobiography. It is a full-on socioeconomic exposé.

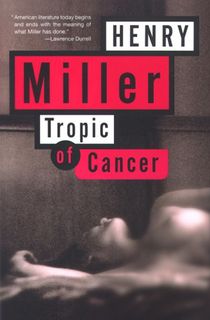

Tropic of Cancer

From the years 1930 and 1934, the American writer Henry Miller was living a life without security or direction. He had abandoned his first wife and a stable job in New York City to flee to Paris and chase the polar opposite of the American Dream. No employer, no salary, decrepit accommodations, and a promiscuous second wife, June Miller, whose escapades he forgave because he was equally unfaithful to her. Paris, essentially, adopted him as a wild, runaway foster child who wouldn’t be subdued. All of this reckless bohemianism was cultivated in his infamous novel Tropic of Cancer.

Miller is considered an ancestor of what would later be termed as the “dirty realism” literary movement, a genre of autobiographical fiction that exposes, without shame or restraint, the gritty reality of existing in long-term poverty, with few avenues for escape. Tropic of Cancer sets out to smash the myth of the free-living artist in Paris as an attractive alternative for those dissatisfied with the nine-to-five lifestyle. Miller had no interest in returning to his former life, yet he also harbored no illusions about the consequences of his choices.

His lightly fictionalized stand-in stumbles through the rough-and-tumble Parisian underground, armed only with empty pockets, an empty stomach, and an overactive imagination that absorbs and records everything like an archivist. He encounters prostitutes, thieves, outcasts, degenerates, and at one point a refugee Russian girl masquerading as a royal expelled from the Revolution (a very common character found on the Parisian streets at the time). This is the book that cemented Henry Miller’s reputation, not only for debauchery but for spoiling many a reader’s fantasy of Paris as a pristine, flawless paradise for creatives.

Paris

Time traveling is like any other kind of traveling. You will enjoy it, but you will also get fatigued and dirty. Such is the experience of reading Edward Rutherfurd’s outstandingly detailed and enveloping historical novel Paris. From the twelfth century all the way up to the 1960s, the people of Paris live their lives, lose their loves, make and squander their fortunes, and guard their secrets, reminding readers through an ever-changing cast of characters that Hollywood’s polished version of Paris often fails to remind its audience just how human Parisians really were, and still are.

The cigarettes at the end of their holders still stunk, as did their streets in the ages of horses, dung, and perfume substituting for bathing. The Eiffel Tower’s erection from 1887 to 1889 wasn’t universally welcomed, nor was its period of construction without its drama and accidents. Wars and revolutions don’t demolish the city completely but rather erode it from the inside. Extramarital love affairs are a hobby. Children’s parentages are dubious.

Paris is a series of episodes reflecting the city’s hidden darkness on both a political and domestic scale. A corrupt king forces an ingenue woman into an arranged marriage. Families sneakily maneuver around their members’ lives to avoid scandals. Courtesans reign over the city while the blueblood elite’s influence dissolves into their last-ever glasses of champagne. And regular, struggling, working families just try to get by, even when historical events resolve to crush them. Through these stories, Rutherford has probably assembled the most real Paris in all of literature.

Featured photo: Pedro Lastra/ Unsplash