In 1948, the world was introduced to the wonderfully large Gilbreth family in Cheaper by the Dozen. The book is semi-autobiographical and was written by two of the Gilbreth’s 12 children, Frank Jr. and Ernestine. Their parents Frank Bunker Gilbreth and Lillian Moller Gilbreth were experts in the emerging field of time and motion studies, a business efficiency technique, and often tested their theories of time management on their family. Cheaper by the Dozen is a collection of charming and hilarious anecdotes of a 14-person family trying to avoid the chaos.

An instant classic, Cheaper by the Dozen has been adapted many times over the years. In 1950, it was adapted into a movie starring Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy as Frank and Lillian. A much later adaptation came in 2003 and starred Steve Martin and Bonnie Hunt. Now, Disney has taken on this classic story! Cheaper by the Dozen, starring Zach Braff and Gabrielle Union, will premiere on Disney+ on March 18, 2022.

Related: Nostalgic Family Movies on Disney+ to Share With Your Kids

Clifton Webb as Frank in the 1950 adaptation.

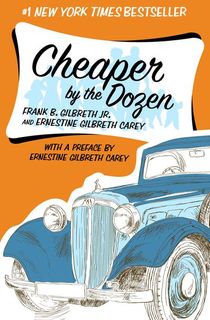

Photo Credit: 20th Century FoxIf you’ve never read Cheaper by the Dozen, now is the perfect time to get acquainted with the Gilbreths. Keep reading for an excerpt from chapter 3 of the book. Here, the authors reminisce about piling all 12 children into the family’s Pierce Arrow car, which Frank nicknamed Foolish Carriage.

3: Orphans In Uniform

WHEN DAD DECIDED HE wanted to take the family for an outing in the Pierce Arrow, he’d whistle assembly, and then ask:

“How many want to go for a ride?”

The question was purely rhetorical, for when Dad rode, everybody rode. So we’d all say we thought a ride would be fine.

Actually, this would be pretty close to the truth. Although Dad’s driving was fraught with peril, there was a strange fascination in its brushes with death and its dramatic, traffic-stopping scenes. It was the sort of thing that you wouldn’t have initiated yourself, but wouldn’t have wanted to miss. It was standing up in a roller coaster. It was going up on the stage when the magician called for volunteers. It was a back somersault off the high diving board.

A drive, too, meant a chance to be with Dad and Mother. If you were lucky, even to sit with them on the front seat. There were so many of us and so few of them that we never could see as much of them as we wanted. Every hour or so, we’d change places so as to give someone else a turn in the front seat with them.

Related: The 6 Best Dads in Literature

Dad would tell us to get ready while he brought the car around to the front of the house. He made it sound easy—as if it never entered his head that Foolish Carriage might not want to come around front. Dad was a perpetual optimist, confident that brains someday would triumph over inanimate steel; bolstered in the belief that he entered the fray with clean hands and a pure heart.

While groans, fiendish gurglings, and backfires were emitting from the barn, the house itself would be organized confusion, as the family carried out its preparations in accordance with prearranged plans. It was like a newspaper on election night; general staff headquarters on D-Day minus one.

.jpg?w=32)

A 1919 Pierce Arrow.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsGetting ready meant scrubbed hands and face, shined shoes, clean clothes, combed hair. It wasn’t advisable to be late, if and when Dad finally came rolling up to the porte-cochere. And it wasn’t advisable to be dirty, because he’d inspect us all.

Besides getting himself ready, each older child was responsible for one of the younger ones. Anne was in charge of Dan, Ern in charge of Jack, and Mart in charge of Bob. This applied not only to rides in the car but all the time. The older sister was supposed to help her particular charge get dressed in the morning, to see that he made his bed, to put clean clothes on when he needed them, to see that he was washed and on time for meals, and to see that his process charts were duly initialed.

Anne, as the oldest, also was responsible for the deportment and general appearance of the whole group. Mother, of course, watched out for the baby, Jane. The intermediate children, Frank, Bill, Lill, and Fred, were considered old enough to look out for themselves, but not old enough to look after anyone else. Dad, for the purpose of convenience (his own), ranked himself with the intermediate category.

In the last analysis, the person responsible for making the system work was Mother. Mother never threatened, never shouted or became excited, never spanked a single one of her children—or anyone else’s, either.

Mother was a psychologist. In her own way, she got even better results with the family than Dad. But she was not a disciplinarian. If it was always Dad, and never Mother, who suggested going for a ride, Mother had her reasons.

She’d go from room to room, settling fights, drying tears, buttoning jackets.

“Mother, he’s got my shirt. Make him give it to me.”

“Mother, can I sit up front with you? I never get to sit up front.”

“It’s mine; you gave it to me. You wore mine yesterday.”

When we’d all gathered in front of the house, the girls in dusters, the boys in linen suits, Mother would call the roll. Anne, Ernestine, Martha, Frank, and so forth.

We used to claim that the roll call was a waste of time and motion. Nothing was considered more of a sin in our house than wasted time and motion. But Dad had two vivid memories about children who had been left behind by mistake.

One such occurrence happened in Hoboken, aboard the liner Leviathan. Dad had taken the boys aboard on a sightseeing trip just before she sailed. He hadn’t remembered to count noses when he came down the gangplank, and didn’t notice, until the gangplank was pulled in, that Dan was missing. The Leviathan’s sailing was held up for twenty minutes until Dan was located, asleep in a chair on the promenade deck.

The other occurrence was slightly more lurid. We were en route from Montclair to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Frank, Jr., was left behind by mistake in a restaurant in New London. His absence wasn’t discovered until near the end of the trip.

Dad wheeled the car around frantically and sped back to New London, breaking every traffic rule then on the books. We had stopped in the New London restaurant for lunch, and it had seemed a respectable enough place. It was night time when we returned, however, and the place was garish in colored lights. Dad left us in the car, and entered. After the drive in the dark, his eyes were squinted in the bright lights, and he couldn’t see very well. But he hurried back to the booths and peered into each one.

A pretty young lady, looking for business, was drinking a highball in the second booth. Dad peered in, flustered.

“Hello, Pops,” she said. “Don’t be bashful. Are you looking for a naughty little girl?”

Dad was caught off guard.

“Goodness, no,” he stammered, with all of his ordinary poise shattered. “I’m looking for a naughty little boy.”

“Whoops, dearie,” she said. “Pardon me.”

All of us had been instructed that when we were lost we were supposed to stay in the same spot until someone returned for us, and Frank, Jr., was found, eating ice cream with the proprietor’s daughter, back in the kitchen.

Anyway, those two experiences explain why Dad always insisted that the roll be called.

Related: Anecdotes from the Real-Life Durrell Family

As we’d line up in front of the house before getting into the car, Dad would look us all over carefully.

“Are you all reasonably sanitary?” he would ask.

Dad would get out and help Mother and the two babies into the front seat. He’d pick out someone whose behavior had been especially good, and allow him to sit up front, too, as the left-hand lookout. The rest of us would pile in the back, exchanging kicks and pinches under the protection of the lap robe as we squirmed around trying to make more room.

Finally, off we’d start. Mother, holding the two babies, seemed to glow with vitality. Her red hair, arranged in a flat pompadour, would begin to blow out in wisps from her hat. As long as we were still in town, and Dad wasn’t driving fast, she seemed to enjoy the ride. She’d sit there listening to him and carrying on a rapid conversation. But just the same her ears were straining toward the sounds in the back seats, to make sure that everything was going all right.

She had plenty to worry about, too, because the more cramped we became the more noise we’d make. Finally, even Dad couldn’t stand the confusion.

“What’s the matter back there?” he’d bellow to Anne. “I thought I told you to keep everybody quiet.”

“That would require an act of God,” Anne would reply bitterly.

“You are going to think God is acting if you don’t keep order back there. I said quiet and I want quiet.”

“I’m trying to make them behave, Daddy. But no one will listen to me.”

“I don’t want any excuses; I want order. You’re the oldest. From now on, I don’t want to hear a single sound from back there. Do you all want to walk home?”

By this time, most of us did, but no one dared say so.

Things would quiet down for a while. Even Anne would relax and forget her responsibilities as the oldest. But finally there’d be trouble again, and we’d feel pinches and kicks down underneath the robe.

“Cut it out, Ernestine, you sneak,” Anne would hiss.

“You take up all the room,” Ernestine would reply. “Why don’t you move over. I wish you’d stayed home.”

“You don’t wish it half as much as I,” Anne would say, with all her heart. It was on such occasions that Anne wished she were an only child.

We made quite a sight rolling along in the car, with the top down. As we passed through cities and villages, we caused a stir equaled only by a circus parade.

Related: The Family That Inspired J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan

This was the part Dad liked best of all. He’d slow down to five miles an hour and he’d blow the horns at imaginary obstacles and cars two blocks away. The horns were Dad’s calliope.

“I seen eleven of them, not counting the man and the woman,” someone would shout from the sidewalk.

“You missed the second baby up front here, Mister,” Dad would call over his shoulder.

Mother would make believe she hadn’t heard anything, and look straight ahead.

Pedestrians would come scrambling from side streets and children would ask their parents to lift them onto their shoulders.

“How do you grow them carrot-tops, Brother?”

“These?” Dad would bellow. “These aren’t so much, Friend. You ought to see the ones I left at home.”

Whenever the crowds gathered at some intersection where we were stopped by traffic, the inevitable question came sooner or later.

“How do you feed all those kids, Mister?”

Dad would ponder for a minute. Then, rearing back so those on the outskirts could hear, he’d say as if he had just thought it up:

“Well, they come cheaper by the dozen, you know.”

This was designed to bring down the house, and usually it did. Dad had a good sense of theater, and he’d try to time this apparent ad lib so that it would coincide with the change in traffic. While the peasantry was chuckling, the Pierce Arrow would buck away in clouds of gray smoke, while the professor up front rendered a few bars of Honk Honk Kadookah.

Leave ’em in stitches, that was us.

Featured still from "Cheaper by the Dozen" via Disney.

.jpg?w=3840)