After spending twenty years of her career teaching literature in Toronto, Janet Somerville became a published author herself. In 2019 she released her first work, Yours, for Probably Always, a nonfiction book about journalist Martha Gellhorn.

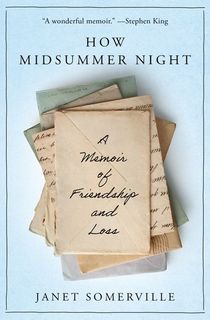

In April 2024 Somerville published a much more personal work: a memoir about her colleague Richard, who was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a rare and inoperable form of brain cancer. In the last months of his life, Somerville began writing letters to Richard, which would eventually become a tribute to his life and teaching career in How Midsummer Night.

Below, read an interview with Janet Somerville.

1. What made you decide to format How Midsummer Night as a series of letters?

I’ve always enjoyed reading archival correspondence as well as collections of letters. They allow you to experience other lives and times without any filter. And, as the often-intended recipient is a singular person, it feels a little bit like snooping into their secret hearts.

Some favorites include The Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, What There Is To Say We Have Said (the correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell), The Selected Letters of Martha Gellhorn, The Hemingway Letters Project, and Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters. By writing to Richard and addressing him in the second person present, I felt close to him again. Through those words he is once again alive. I hope readers will feel the same way. That he becomes their friend, too.

2. Throughout your memoir, lines from musicals provide relief from the bleak reality of Richard’s illness. Why do you think musicals have the ability to bring so much comfort?

Musical theatre was in Richard’s bones, so it was a natural fit to provide comic relief. One of the things that’s great about musicals, especially musical comedies, is that they address big life themes: friendship, family, loyalty, betrayal, love, joy. We can all relate to some aspect of it. The fact that it’s communicated through song and dance, orchestration, as well as the “book” of the show makes it a comfort. We feel our shared humanity in musical theatre.

3. You spent twenty years of your career teaching literature in Toronto. Do you think that has made you a better writer? How have your students influenced your work?

Teaching literature certainly made me a better reader, because when you teach a book you have to engage with it on many levels. Because I taught in Toronto, I was able to invite novelists, screenwriters, and poets into the classroom. In fact, I’d include their books on the curriculum, so there was an added impetus for students to engage with that writing in order to try to impress the authors when they visited the school. Teenage boys are competitive!

Also, when I was teaching a Grade 12 course called The Writer’s Craft I often did the writing assignments with the students. I mean, I actually drafted pieces as they drafted pieces and shared my work aloud as they did. I think that gave me credibility as far as they were concerned, and they appreciated that I was willing to take the risk of revealing my own raw, unedited pieces just as they were required to do.

We worked in many genres: poetry, memoir, travel writing, flash fiction, screenwriting… A few of my students have gone on to be professional writers and I’m absolutely delighted by their success.

4. You’ve also written a book about Martha Gellhorn—what sparked your interest in her?

A book-loving Twitter pal in Fife, Scotland suggested I read her selected letters edited by Caroline Moorehead. So I did. And then I read everything of Gellhorn’s I could find that was still in print. Although she was most known for her war correspondence during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s and during World War II, so much of what she wrote felt like it could have been written last week. She had such a contemporary voice. Her outrage at the state of the world spoke to me. She was determined, throughout her long life, to “make a tiny, squeaking noise about the wrongness of things.” And, she did.

From the treatment of Spanish refugees in 1938 to the liberation of Dachau in 1945—about which she’d say, “It was as if I fell over a cliff and never recovered”—to the world’s ignorance about the murdered street children of Brazil in the 1990s, Gellhorn looked while others looked away. Her words are for all time, and for much of her professional life she was relegated to a footnote as Hemingway’s third wife. I wanted to introduce her to a new generation on her own terms.

5. What’s the last book you read that you wanted to tell the world about?

When I’m asked what I recommend for someone who wants to be lifted up these days, I say, without a doubt, Sarah Winman’s Still Life. It’s wholly immersive and you feel like the characters could be in your life, making it better. They are such sublime company. It’s set in London and in Florence from the turn of the twentieth century through to the 1980s. It’s about strangers who meet and become family. And it’s about art and truth and beauty. Absolutely irresistible. Winman, an actor as well as a novelist, performs the audiobook and it is perfection.

How Midsummer Night

“A stunning memoir…a gorgeous heartbreaker.” —Ellen Barkin