Maria Callas was one of the most lauded and influential opera singers of the 20th century. Born to Greek immigrant parents in Manhattan, Callas moved to Greece when she was thirteen to study music. From there, she ventured across the Ionian Sea to begin her career in music, a move that would change not only her life, but the entire trajectory of contemporary opera, forever.

Callas's story is equal parts triumph and tragedy. She garnered international acclaim for her unparallelled bel canto technique, reviving roles with her powerful and versatile voice that no one had dared to touch in decades. She performed all over the world, from La Scala in Milan to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, earning herself the title of “La Divina” (The Divine One) for her outstanding performances.

For all her success, Callas also struggled immensely in her personal life, and her later years were embroiled in scandal. Her career declined prematurely as a result. She spent the last year of her life isolated in Paris, where, in September 1977, she suffered a fatal heart attack and passed away at the age of 53.

New buzz has been generated around Callas's name thanks to a recent Netflix biopic directed by Pablo Larraín and starring Angelina Jolie as Callas. While critics have praised Jolie's acting, many have argued that the film fails to capture the magnificence of Callas's story, both as a singer and as a person.

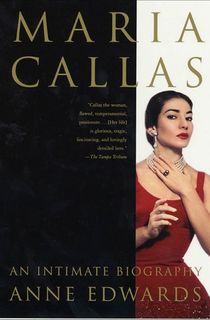

If you crave an in-depth account of the glory and tragedy of contemporary opera's most iconic singer in a way the biopic doesn't quite capture, then Maria Callas: An Intimate Biography is absolutely the book for you.

THE JEWEL-LIKE Teatro La Fenice may not have been the largest opera house in the world, but it was the most beautiful with its Venetian gold-encrusted boxes rising to the magnificent domed ceiling covered in fanciful murals painted in the seventeenth century against della Robbia blue skies and feathery white clouds. The world’s most celebrated singers had appeared at La Fenice, usually in the summer months, Venice’s tourist season, which fortuitously coincided with the time when La Scala, the Met and Covent Garden were closed. Maestro Serafin would conduct and the cast of Tristan und Isolde that Maria joined was a stellar ensemble including Fiorenzo Tasso as Tristan, Fedora Barbieri as Brangaene and Boris Christoff as King Mark. The winter season at La Fenice drew some of Italy’s most discerning and knowledgeable opera-goers and critics. Maria would now find out if she had the ability to become a world-class artist.

Her four weeks in Rome working with Serafin had been gruelling but also tremendously rewarding. Each day included eight to twelve hours of study, practice and rehearsal. She was the guest of the Maestro and his wife, Elena Rakowska, Battista remaining behind in Verona, where both his family and friends were trying to convince him to break off his relationship with Maria. They claimed his attention to her had caused him to neglect the family business and was creating unwelcome gossip. The idea that a wealthy, fifty-two-year-old man could be having an affair with a twenty-three-year-old singer with no means was shocking. Pomari worried about what the Board of the Verona Festival would make of that unseemly news. Battista had his own agenda and turned a deaf ear. Maria would be his passport into a more international world. He could hardly wait for the four weeks to end, when they could meet again in Venice, his hope being that if her Isolde was a grand success, he could tie up his business ends in Verona and become a full-time opera impresario.

Battista had yet to propose and Maria was anxious that he might lose interest with her being at such a distance for a month. Jackie’s plight was in her mind. The two sisters corresponded and Jackie’s letters were filled with the horrors of Milton’s progressive illness and the insulting way she was being treated by his brother and other members of his family who referred to her as ‘Milton’s whore’ and were doing all they could to see that when he died she inherited nothing.

‘You cannot imagine how much I miss you,’ Maria wrote to Battista from Rome. ‘I cannot wait until I am in your arms again.’

Her longing for Battista did not interfere with her dedicated work on her role and her attention to Serafin’s instruction. Maria immediately recognized how much Serafin could give her and in these four weeks a close relationship, one might even call it a collaboration, was begun, which would become the greatest influence in the final emergence of Maria as a true artist.

‘He opened a new world to me,’ Maria said many years later, ‘showed me there was a reason for everything, that even fioriture1 and trills have a reason in a composer’s mind … that they are the expression of the … character, that is the way he feels at the moment, the passing emotions that take hold of him. He would coach [me] for every little detail, every movement, every word, every breath … He taught me that pauses are often more important than the music.’

Serafin also insisted Maria have special costumes made for her role. ‘Why? Is this necessary?’ she asked, concerned about the cost, which she could not afford and would have to ask Battista to pay for.

‘The first act of Tristan is ninety minutes long,’ he replied. ‘And no matter how much you fascinate the public with your voice, they still have all that time to look you over and cut your costume to pieces. So your appearance on stage must be harmonious with the music.’

To Battista from Rome, in the same letter in which she thanked him for sending the money required, she wrote: ‘The more I sing Isolde the better she develops. It is rather an impetuous role, but I like it … Yesterday I heard Serafin speaking on the telephone so glowingly of me to Catozzo [the vocal coach in Verona] that I was moved to tears … How I would like you Battista to be near me … If I express all my feelings of you through Isolde, I will be marvellous.’

She arrived in Venice in mid-December and was met by Battista. She wept with happiness and he embraced her warmly. Venice looked so different, the buildings that surrounded the Piazza San Marco, its golden beauty of the previous summer now sepulchral in the grey light of winter. Most of the tourists were gone but there was still a great deal of activity. The next morning she and Battista had breakfast in the same café off the Piazza San Marco where they had lunched in June, listening to the marangoni bells that for centuries had proclaimed the beginning and the end of Venice’s working day.

She was to have her first rehearsal a few hours later and was nervous, and Battista did what he could to calm her. He had a habit of speaking in a rat-a-tat way, words popping out like small bullets. ‘Mia cara, mia cara, all will be well. I believe in you. The Maestro believes in you. Trust him. Trust me.’

She did, but she also knew that it was she who would be judged. She entered into the rehearsals with fierce intensity, singing full voice at all times while the other cast members saved their voices. As always, she was the first to arrive at rehearsals and the last to leave. Battista seldom left the theatre, sitting in the back row when she was on stage and nearby when she was resting in her dressing room. On the evening of 30 December, the first performance, he stood in the wings watching her as she made her entrance and waited for her there as she came off stage, whispering encouragement: ‘Go on, Maria! There’s no one like you. You’re the greatest in the world!’