Both in America and all over the world, people from different backgrounds often have trouble finding common ground. We see the effects of this in everything from microaggressions to economic inequality between different groups, to much more overt displays of aggression, such as hate mail and outright attacks.

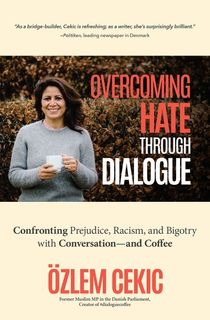

Özlem Cekic, a Muslim PM in the Danish government, is all too familiar with being hated for her culture. But when a friend suggested she was just as judgmental as the racists who hated her, she decided to stop ignoring her harassers, and start engaging with them. This led to her book, Overcoming Hate Through Dialogue, in which Cekic details her discussions with the very people who sent her hate mail.

Below, read an excerpt from the first chapter of Cekic’s novel.

WHY DO THEY HATE YOU?

“Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.”

—Albert Einstein

As a Turkish immigrant born to Kurdish parents, I became one of the first ethnic minority women to win a seat in the Danish Parliament in 2007. It was also the year I began receiving hate mail. It’s amazing how quickly I got used to finding my inbox full of hate.

“What’s a Paki like you doing in our parliament?” they’d write. “You don’t belong here!” Or simply, “Terrorist.”

Delete. Delete. Delete. I never even considered replying. We had absolutely nothing in common; they didn’t understand me, and I didn’t understand them. As far as I was concerned, engaging with anyone so entrenched in their own ignorance would have been a complete waste of time and effort.

Then, one day, my colleague suggested I should save these messages. “If nothing else,” she said, “they’ll be useful to the police when something happens to you.” I noted that she said “when” something happens, not “if.”

Though I didn’t really believe it would come to that, I took her advice and started saving every email that arrived. For a while, they were simply filed and forgotten. That is, until things took a more worrying turn. In 2008, I returned from my summer vacation to find a card in my mailbox. It was decorated with the Danish flag, and since, in Denmark, we use the flag to mark any festive occasion, my first thought was that it must be a party invitation.

But inside was something rather different. “Return tickets home. Go back to your terrorist brothers.” These greetings had come from the Danish Association—an organization with deep roots in Denmark’s extreme right. That they knew my address was frightening enough. But when I examined the envelope, I saw, to my horror, that there was no stamp. It hadn’t arrived by post; it had been delivered by hand.

In my mind, that changed everything. The reassuring distance I thought I’d established between me and my abusers—between my kids and my abusers—had suddenly evaporated. Whoever these people were, they were too close for comfort now.

Immediately, I took steps to remove my address from public records. I made sure that the names of my children’s daycare and schools were not publicly available either. But, at the same time, I knew that the more involved I became in parliamentary debates, the more I would attract this kind of attention, and the steadier the stream of threats and abuse would become.

These threats ranged from the vague (“We know where you live”) to the terrifyingly specific (“The day you become a minister, we will cut your throat”). I received them; I read them; I passed them all on to the police. This became my new normal.

But in the spring of 2010, a neo-Nazi began to harass me. I couldn’t dismiss his actions as an idle threat to my safety. This was a man who had previously attacked Muslim women in the street. For more than eight months, he called me day and night—sometimes upwards of forty times a day. I had become his obsession.

One day, while I visited the zoo with my kids, my phone rang. I ignored it, certain it was him. We had just arrived and had only gotten as far as the lions’ den. I was determined not to allow him to ruin our day. But when I saw his text, I panicked.

Convinced that he was at the zoo—and that he was watching us—we got out of there fast.

When we were back at home, my son Furkan asked, “Mum, why does he hate you so much, when he doesn’t even know you?”

I told him, “Some people are just stupid.” At the time, I thought that was a pretty clever answer. “We’re the good guys. They’re the bad guys. That’s all you need to know.”

But how I wish it were that simple. The truth was this man had upended my life. He was the reason I parked my car in a different spot every night when I came home; the reason I constantly looked over my shoulder in the street; the reason I could no longer enjoy a day out with my children.

Several weeks after the incident at the zoo, I confided in my photographer friend, Jacob Holdt. Jacob had documented racism in the United States in his book American Pictures, so I was sure he was the right shoulder to cry on.

Tearfully, I told him my fears, and about the fury I felt over the restrictions this neo-Nazi idiot’s behavior had created in my daily life. I waited for words of comfort and reassurance. Instead, his response knocked me sideways.

“You’re just as judgmental of people like them as they are of people like you,” he said.

I was stunned. I’m no racist! Is that what he was accusing me of? Sure, if I were to be totally honest, there had been times in my life when I had hated other people. Certain groups, who, I knew, hated me right back. But I had grown into an open-minded, liberal human being, right? I’d put it all behind me. Hadn’t I?

Related: What White Fragility Gets Wrong, and 5 Books to Read Instead

“How many of your friends and family vote for right-wing parties?” he asked. “Do you even talk to people who do?”

I had to admit it: None. And no.

In fact, for a long time, this had been a source of pride for me. I often boasted to my friends that I never shook hands with MPs from the alt-right Danish People’s Party. I was proud of the distance I had created between myself and them. I never questioned whether I was right in doing so, until Jacob suggested, “Go out and meet them. Your son deserves a better answer.”

“Meet them?! They’d kill me!” I said.

“They don’t kill MPs,” Jacob said, before adding with a wry smile, “In any case, if they do, you’ll be a martyr. Win-win.”

I can’t say that I found the prospect of martyrdom very reassuring at that point. But Jacob had planted the seed of an idea. So when, in the autumn of that year, the police tracked down the man who had been hounding me, I took a deep breath and suggested a mediation meeting. He refused, but I wasn’t giving up.

It was clear to me that ignoring hate didn’t simply make it disappear. I had to understand it better—I had to know why so many people hate Danish Muslims like me—and the obvious place to start was my inbox.

There were, by then, hundreds of emails. Several had come from the same handful of senders. Most began by addressing me as “Paki,” “terrorist,” “Muslim rat,” or “whore.” When it comes to insults, the Danish language is wonderfully diverse. I decided to contact a few of the people who’d emailed me.

My aim was not so much to get to know them, as Jacob had suggested, as it was to convert them to righteousness. I’m not sure what sort of miracle I imagined would occur when my haters finally came face-to-face with a Muslim. Perhaps I hoped that, by confronting them with their own prejudices, I could somehow cure them of making these baseless generalizations about us. I wanted to be a paragon of virtue: living proof that there are Muslims who work, abide by the law, and support democracy.

Today, I can see this as delusional. But back then, at the start of all this, I saw myself as a savior on a mission. Armed with a sense of justice, I sat down to type, and, before I knew it, I was inviting myself for a visit. And that’s how the coffee dialogues began, and how, since the winter of 2010, I have sought out coffee and conversation with people I know harbor hatred toward me and people like me.

What began with that email has led to hundreds of encounters. Each one is another step toward understanding prejudice—my own, as well as theirs. Over time, I’ve given up on being a savior. I’ve learned not to try to convince people of anything, or to attempt to make them “good.” Instead, I just listen—and try to discover where their feelings of impotence, fear, and hatred originate.

I’ve discovered that, no matter how abusive a person may be, they still serve cake with their coffee. And every time I begin a dialogue with coffee and cake on the table, I’m reminded of how right Jacob was when he told me I needed to confront my own racism.

Via Alex / Unsplash

The first of these meetings was with Ingolf, and I will never forget it. His email was brimming with bile. “All you care about is taking whatever you can for yourself and your kind,” he wrote.

In my imagination, Ingolf was the embodiment of hatred: hard, nasty, and twisted. Before we met, I imagined the moment I would shake his hand, with its long, dirty fingernails, and enter his pigsty of a home. So imagine my disappointment when he opened his door and revealed himself to be a perfectly respectable-looking gentleman. He served coffee in the same coffee set that my parents have at home.

As expected, our conversation revealed that we disagreed on many things. Ingolf’s views on Danish Muslims were extreme. Among other things, he had helped found Radio Holger, a radio station that caters to a neo-Nazi audience.

But we also had a lot in common. We shared the same type of working-class background, and even some of the same prejudices. I remember Ingolf telling me how angry he got whenever a “raghead” bus driver stopped ten meters away from where he was waiting at the bus stop. Immediately, I recognized that feeling. I told him that, when I was younger, if a bus didn’t stop for me, I was sure that the driver was a racist. It struck me then that what we believe to be conscious acts of malice are often just innocent mistakes.

It was a shock to me that Ingolf could possibly feel as discriminated against as I did. But he did. Listening to him, I had to confront my own judgments. He was neither evil nor stupid. He was angry.

My meeting with him was the first of many meetings with racists, which turned into a reevaluation of my own preconceptions, interpretations, and generalizations. I have been surprised by how much I have found in common with the people I have visited—and the extent of my own racist prejudice.

Want to keep reading? Download Overcoming Hate Through Dialogue today.

Overcoming Hate through Dialogue

“If you think this project and book title sound sentimental and touchy-feely, keep reading. You’ll soon be applauding the writer. The writer’s enormous emotional investment in humanity is made evident by well-written passages which reveal the strength of the book and its greatest accomplishment: giving a familiar face to those who hate.” ―Dagbladet Information