On December 29, 2024, President Jimmy Carter passed away at the age of 100. The 39th President of the United States presided for only one term, from 1977 to 1981. But while he was unsuccessful in his bid for reelection, his reputation changed decades later, in large part thanks to his humanitarian work which earned him the Novel Peace Prize in 2002.

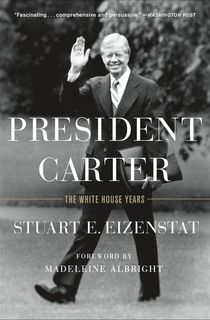

In 2018, Stuart Eizenstat published what is considered the definitive biography on Jimmy Carter's time as president. Eizenstat worked with President Carter from his political rise in Georgia and served as Chief Domestic Policy Advisor during his time in the White House. Famous for his legal pads and fastidious note-taking, Eizenstat drew on his own notes, memories and interviews to write a comprehensive history of, in his words, a presidential term that was “one of the most consequential in modern history.”

Below, read an excerpt from President Carter.

Every four years a handful of talented men and women, mainly elected public officials or business leaders, have the audacity, self-confidence, and determination to put themselves and their families through the hell of a presidential campaign in the belief that they are fit to make decisions that affect the lives of hundreds of millions in the United States and billions more people around the world. Their motives are as varied as their personalities, but all are consumed with ambition to accomplish great things. They see the presidency as the way to mark the world with their deepest convictions.

It is conventional wisdom that Jimmy Carter was a weak and hapless president. But I believe that the single term served by the thirty-ninth president of the United States was one of the most consequential in modern history. Far from a failed presidency, he left behind concrete reforms and long-lasting benefits to the people of the United States as well as the international order. He has more than redeemed himself as an admired public figure by his postpresidential role as a diplomatic mediator and election monitor, public health defender, and human rights advocate. Now it is time to redeem his presidency from the lingering memories of double-digit inflation and interest rates, of gasoline lines, as well as the scars left by the national humiliation of American diplomats held hostage by Iranian revolutionaries for more than a year.

Let me be clear: I am not nominating Jimmy Carter for a place on Mount Rushmore. He was not a great president, but he was a good and productive one. He delivered results, many of which were realized only after he left office. He was a man of almost unyielding principle. Yet his greatest virtue was at once his most serious fault for a president in an American democracy of divided powers. The Founding Fathers built our government to advance incrementally through deliberation and compromise. But Carter took on intractable problems with comprehensive solutions while disregarding the political consequences. He could break before he would bend his principles or abandon his personal loyalties.

An extraordinarily gifted political campaigner, he nevertheless believed that politics stopped once he entered the Oval Office and that decisions should be made strictly on their merits. Carter reflected later that it was “a matter of pride with me not to let the political consequences be determinant in making a decision about an issue that was important to the country … because the political consequences are not just whether I am going to get some votes or not, but how much public support I will have for the things I’m trying to do. And I have to say that I was often mistaken about that.”

To be truly effective, a president cannot make a sharp break between the politics of his campaign and the politics of governing if he wants to nurture an effective national coalition. This Carter not only failed to achieve—he did not want to. Time and again he would say, “Leave the politics to me,” while in fact he disdained politics. He believed that if he only did “the right thing” in his eyes, it would be self-evident to the public, which would reward him with reelection. However, politics cannot be parked at the Oval Office door, to be brought out only at election time, but must be kept running all the time by cultivating your political base and mobilizing the broader public, its elected representatives, and the interests they speak for, on behalf of clearly defined priorities. They can never be ignored in order to solve problems and to do good. The presidency is inherently a political job: The president is not only commander in chief but politician in chief.

Carter was so determined to confront intractable problems that he came away at times seeming like a public scold—a nanny telling her charges to eat their spinach, for example when he urged Americans to turn down their thermostats to reduce dependence on imported oil. When he summoned outside advisers to Camp David to help him right his ship of state, one young first-term governor from another Southern state advised him: “Mr. President, don’t just preach sacrifice, but that it is an exciting time to be alive.” The advice came from none other than William Jefferson Clinton, the new governor of Arkansas. This was not a natural instinct for Carter, who focused more on the obstacles to a better country and safer world than on the rewards that could be enjoyed.

Presidents who leave the White House under a cloud can emerge in the clear with the perspective of history. Who today pays attention to contemporaneous charges that Harry Truman was corrupt and soft on Communism, leaving the White House with an approval rating hovering close to a mere 20 percent, when we now appreciate that he helped construct an international order that lasted for half a century? The remarkable domestic legacy of President Lyndon Johnson, on whose White House staff I served, was totally overshadowed by Vietnam—until the fiftieth anniversaries of his landmark bills led to new reflection about his presidency. Bill Clinton, in whose administration I also served, paid a heavy price for a tawdry personal affair. But his significant accomplishments and extraordinary political gifts helped restore him to a position of affection. His immediate predecessor, George H. W. Bush, was dismissed as a silver-spoon president who lost the support of his own party by reversing his commitment never to raise taxes, but it is now evident that he deftly managed the end of the Cold War and avoided the triumphalist trap of chasing Saddam Hussein back into his lair in Baghdad.

Nevertheless critics still disregard the breadth of Carter’s accomplishments and accuse him of being an indecisive president That is simply not true; if anything, he was too bold and determined in attacking too many challenges that other presidents had sidestepped or ignored, such as energy, the Panama Canal, or the Middle East, while nevertheless achieving lasting results. He reflected that if he had concentrated on a “few major issues, it would have given an image of accomplishment.” The art of presidential compromise rests on the ability to obtain at least half of what the administration proposes to Congress and then to claim victory. President Carter was maladroit at this political sleight of hand largely because he was uncomfortable with compromising what seemed to him so obviously the right course.

He was also unable to develop the close relationships necessary to persuade others who might not fully share his principles, despite having weekly Democratic congressional leadership breakfasts without fail when he was in town, and many with the Republican leadership. Yet because of his vision and determination, he actually came away with much of what he wanted, while obtaining it in a manner that made it appear he had caved to pressure and lost.

One reason his substantial victories are discounted is that he sought such broad and sweeping measures that what he gained in return often looked paltry. Winning was often ugly: He dissipated the political capital that presidents must constantly nourish and replenish for the next battle. He was too unbending while simultaneously tackling too many important issues without clear priorities, venturing where other presidents felt blocked because of the very same political considerations that he dismissed as unworthy of any president. As he told me, “Whenever I felt an issue was important to the country and needed to be addressed, my inclination was to go ahead and do it.”

In advancing what is admittedly a revisionist view of the Carter presidency, my perspective benefits not only from the passage of time but from my White House position as his domestic-policy director. I have admired him since I first worked as his policy adviser during his successful 1970 campaign for governor of my home state of Georgia, as well as in his presidential campaign, and I was proud to serve him as one of his closest presidential aides. I was at his side as he made the kinds of decisions that only presidents are called upon to make, where there are often no good options. I was only one of a handful of aides with direct phone lines to the president in my office and home. Every domestic and economic issue passed across my desk, as well as every major piece of legislation. In foreign policy I was kept informed of many decisions even when I was not directly involved. And I was significantly involved in the Middle East, particularly relations with Israel, as a back channel, and with American Jewry, stemming from the president’s peace initiatives, as well as with the sanctions arising from the Iranian hostage crisis, and those against the Soviet Union after it invaded Afghanistan.

Inside the White House I was renowned—or, more accurately, the butt of jokes—for my yellow legal pads. There were more than one hundred of them, over five thousand pages, on which I took detailed, often verbatim notes of every meeting I attended and all my telephone conversations, not with the thought of writing a book but as a discipline to stay on top of the issues that it was my job to coordinate. The pads have been essential in writing this book. Over more than three decades, I also conducted more than 350 interviews of almost every major figure in the administration and many outside with a special perspective, including five with Carter himself, two with Rosalynn Carter, and several with Vice President Walter Mondale. I have also been granted access to now-declassified documents at the Carter Presidential Library, including my private memos as well as those of other key officials. These newly released documents also include the daily Evening Reports from Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and Weekly Reports from National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski.

This level of access, at once both wide and intimate, gives this book its authority. I knew from the outset that it could be taken seriously only if I also accepted the responsibility of telling an unflinchingly honest story of Carter and his administration. I have not shirked analyzing the failures and limitations of his presidency (including my own), secure in the knowledge that they are already better known than his lasting accomplishments. The risk is that skeptics may conclude this only confirms their impressions of Jimmy Carter. On the contrary, I count showing the negatives along with the positives as a sign of my credibility as both participant and author of a book that is part memoir and part an effort to set the historical record right.

But even with Carter’s limitations, I refuse to let the mistakes overwhelm the achievements. We still benefit from his vision of the challenges faced by our country and the world; from his willingness to confront and deal directly with them regardless of the political cost; and finally from his essential integrity. He gained the presidency in a post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era of cynicism about government with a personal pledge that “I will never lie to you”—a promise that he worked hard to keep, and is now more important than ever in a new era of “fake news” and post-truth political rhetoric.

Want to keep reading? Download President Carter now.

President Carter

"Stuart Eizenstat’s book is something we rarely see ― an illuminating, vital and elegant combination of White House insider’s memoir and well-researched history. His excellent work shows us important new dimensions of Jimmy Carter and his Presidency and deserves to be widely read.”

―Michael Beschloss, NBC News Presidential Historian and New York Times bestselling author of The Conquerors