On September 2, 2022, Sterling Lord passed away at the age of 102. One of New York's top literary agents, Lord represented works such as On the Road, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Wise Guys (which would be adapted by Martin Scorsese into Goodfellas), and countless more books and authors over his career.

In 2013, Lord's client Joe McGinniss told The New York Times that "Sterling’s career encapsulated the rise and fall of literary nonfiction in post-World War II America. He was the last link to what we can now see not so much as a Golden Age, but as a brief, shining moment when long-form journalism mattered in a way it no longer does and may never again.”

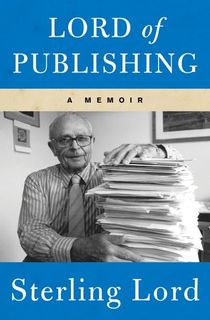

That same year Lord published his own memoir, Lord of Publishing. In his work, Lord delves into what many consider the greatest era of book publishing, and how his work played a role in it.

Below, read an excerpt from Lord of Publishing, in which Lord describes his first meeting with Jack Kerouac, and his trials in selling On the Road.

1

Kerouac and Me

He rang the bell and walked through the door of my office, a below-ground-level room I had liberated from being a one-room-plus-bath studio apartment just off Park Avenue. He was wearing a light-colored weather-resistant jacket with a lightweight checkered shirt underneath. He was striking looking—“diamond in the rough” was the phrase that came to mind.

Two weeks earlier, legendary literary editor Bob Giroux of Farrar, Straus and Giroux had called to alert me that Jack Kerouac would be coming by. Giroux was one of the first established editors I had met. He had called and introduced himself and then took me to lunch. Obviously he wanted to meet the new kid on the block, and in particular he had heard that my client Ralph G. Martin was working on a book that he—Giroux—might like to see. The Martin project never developed, but the Kerouac did. I’d heard of Kerouac but knew very little about him. Giroux had edited The Town and the City, Jack’s first and only conventional novel. Jack had just been to see him—it was 1952—and he needed a literary agent. Giroux thought I would be the right man. I was two years older than Jack, and as a starting agent, I had a good deal of energy and time. He added that Jack had typed his new manuscript on a 120-foot scroll of architectural tracing paper. That would be my problem, Giroux said.

Jack had the manuscript wrapped in a newspaper, which he extracted from a weather-beaten rucksack. He called it The Beat Generation, and he had already taken Bob Giroux’s advice and retyped it on regular typing paper. He was courteous and respectful, but we didn’t talk at length. He was leaving the product of years of work (and three weeks of typing) in my hands. He told me Giroux had rejected it.

Related: 15 Famous Books That Were Initially Rejected

It was actually the first novel submitted to me in my agency work, and I read it carefully, carving out time from the demanding nonfiction projects on my calendar. I was really taken with it. I called Jack and told him how strongly I felt about the manuscript and that I was ready to go with it. I felt that his was a fresh, distinctive voice that should be heard.

As we started working together I came to respect him and he, me. That mutual respect prevailed over all the differences in our backgrounds. Jack had grown up in Lowell, Massachusetts, a mill town, and came from a working-class family. I’d grown up in a middle-class family in a primarily white, comfortable Midwestern city and had a nondramatic traditional upbringing (before World War II). I was impressed with Jack’s commitment to serious writing at the expense of everything else in his life. At a time when the middle class was burgeoning with new homes, two-tone American cars, and black-and-white TVs, when American happiness was defined by upwardly mobile consumerism, Kerouac etched a different existence and he wrote in an original language.

Jack was handsome, and in a bar or a crowd I noticed women thought so, too. He had dark eyes and prominent eyebrows set off by ruddy skin. I don’t recall his ever wearing a suit and tie into my office. He dressed in a slightly disheveled way, which was not an affectation; it was just Jack. In public, he bore an intense look, though when he was among family and friends he would offer enough of a smile so you knew when he was happy. He was articulate, careful in his speech. He did not talk the way he wrote.

Jack felt comfortable with me and with other friends, but I saw he was shy and did not do well in public. I think that was why, at least in part, he drank so much. When he drank he may have been a little less shy, but he was not obstreperous.

“Sometime in the early 1960s, I noticed newspaper ads for an insurance company, the name of which I don’t remember, which referred to their friendly neighborhood agents. I didn’t know any friendly neighborhood insurance men myself, and it seemed a little ridiculous, but it was a catchy phrase, so I started signing my letters to Jack Kerouac, “Your friendly neighborhood literary agent.” Jack did have a sense of humor. It wasn’t evident very often, but one sunny day I got this letter (above), which not only copied my friendly neighborhood reference, but gave his regards to Broadway. In all our years together, it was the only letter I received from him that was so openly humorous.”

Photo Credit: Allen Ginsburg TrustBook publishing was still very traditional then, and I was not totally surprised or discouraged with one rejection after the other. For four years I could not find an editor or publisher who shared my enthusiasm for On the Road.

The most striking rejection was from Joe Fox at Knopf, a publishing house known for the high quality of its books and for which Joe was one of the very best young literary editors at the time. Kerouac, Joe said, “does have enormous talent of a very special kind. But this is not a well-made novel, nor a saleable one nor even, I think, a good one. His frenetic and scrambling prose perfectly expresses the feverish travels, geographically and mentally, of the Beat Generation. But is that enough? I don’t think so.”

Jack found the rejections too depressing. On June 28, 1955, disheartened by my lack of success, he wrote me that he wanted to “pull my manuscripts back and forget publishing.” I noticed he was not saying he was discouraged about writing; it was publishing that discouraged him, and of course most of the male editors working at publishing houses at that time were from a very different generation. I thought I knew Jack well by then, so I ignored his request and continued submitting. Twelve days later he changed his mind and we went on as before. I still believed his work would eventually be published.

Related: Beyond On the Road: The Other Jack Kerouac

I had already begun to realize how subjective the publishers’ decisions were and to rely on my own judgment. Jack told me he believed in me and my judgment, which helped.

After almost four years of trying to sell Jack’s manuscript, I sold a piece of his to the Paris Review with the help of Tom Guinzburg, an editor at and soon-to-be president of Viking Press, and a board member of the Paris Review. He had read Kerouac and already believed in Jack. A few months later, I sold one, then another piece from the manuscript to New World Writing, a literary magazine in pocket-book format, published then by New American Library. Shortly after the second story appeared, I had a call from Keith Jennison, a young Viking editor. He, Malcolm Cowley—a distinguished literary critic and associate editor at Viking—and Tom Guinzburg were the strong Kerouac fans at Viking.

“Dammit, Sterling,” Keith said, “we can’t let that manuscript go unpublished any longer.” He made me an offer of $900 against royalties. I said no, got him up to $1,000, and closed the deal. Jack took the good news in stride. He had come to believe the book would eventually be published, and its happening now was merely a confirmation of his belief.

Shortly after the contract was signed, Helen Taylor, an experienced senior editor, whose first love was music, began working with Jack to edit the manuscript, while the lawyers expressed their concerns about the names and likenesses of some of the book’s characters. She and Jack had an initial struggle over style. Her editing was extremely sensitive. She made cuts and very minor changes without in any way impeding the flow of Jack’s prose, although that wasn’t how Jack felt. The two came to an understanding. Jack’s understanding.

Related: Ending a Sentence With a Preposition and More Grammar Myths Busted

In an extraordinary letter to Helen—extraordinary because Kerouac had not yet become the Jack Kerouac—he wrote in almost defiant language what he demanded of his editor and publisher. He left no doubt who was in charge. And for any skeptic who might have thought his book was only the underdeveloped essays of a free spirit and not the thoughtful writing of an exacting writer, this letter alone would dispel the myth:

Dear Helen,

Here are the galleys exactly as I want them published. I want to be called in to see the final galley and check it again against my original scroll, since I’m paying for this and my reputation depends on it . . . Just leave the secrets of syntax and narrative to me.

He then went comma by comma, explaining why he’d done what he’d done. For example, he wrote:

My “goodbye” (the spelling of it) is based on the philological theory and my own belief that it means “God be with ye” which is lost in the machine-like “good-by.”

He advised her that he’d written “I was seeing the white light everywhere everything,” not “the white light everywhere, everything.”

He was not averse to having an editor. Jack acknowledged that in an entire manuscript he might have ten or twelve “mistakes or serious problems.”

In a friendly tone, Jack suggested that on his next manuscript, they could thrash it out together, but, he warned, “no more irresponsible copy-editing of my Mark Twain Huckleberry Finn prose.”

By then, he and Helen had an understanding, and so he concluded:

With freedom in mind I can write a book for every October.

See you soon, and mucho thanks.

Jack

Want to keep reading? Download Lord of Publishing now.

Lord of Publishing

A frank and insightful memoir of a life spent in publishing, by one of literature’s most legendary agents.

Sterling Lord has led an extraordinary life, from his youth in small-town Iowa to his post-war founding and editing of an English-language magazine in Paris, followed by his move to New York City to become one of the most powerful literary agents in the field. As agent to Jack Kerouac, Ken Kesey, and countless others—ranging from Jimmy Breslin and Rocky Graziano to the Berenstains and four US cabinet members—Lord is the decisive influence and authors’ confidant who has engineered some of the most important book deals in literary history.

In Lord of Publishing, his memoir of life and work (and tennis), Lord reveals that he is also a consummate storyteller. Witty and wise, he brings to life what was arguably the greatest era of book publishing, and gives a brilliant insider’s scoop on the key figures of the book business—as well as some of the most remarkable books and authors of our time.