For 15 minutes in the summer of ’66 I was a Warhol girl, thanks to Nico, an otherworldly ice cool beauty from Berlin who had just arrived in Provincetown, Massachusetts with Lou Reed, John Cale and the Velvet Underground.

They were putting on a show at the Chrysler Art Museum as part of the ‘Exploding Plastic Inevitable’, a multimedia extravaganza featuring their ground-breaking nihilistic music, ‘whip’ dancing with Mary Woronov and Gerard Malanga, a mind-blowing light show, and Warhol’s mind-numbing underground films.

I desperately wanted to catch the concert, but was ‘performing’ as a folksinger fill-in down the street at the Blues Bag, and feared I might never get a chance to meet the fabled group, when fate intervened in the form of the Provincetown authorities, who, afraid for other reasons, broke up the EPI’s act. Not only was sadomasochism and heroin-shooting being realistically portrayed right on stage, but the belts and whips had been ‘borrowed’ from a local leather shop.

With no show to do—and backed up toilets in their rental house, Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground and Nico magically appeared at the back door of the broken-down beach house where I was staying. (There might have been a mutual musician friend involved.)

Related: Books to Read Before You Watch the New Velvet Underground Documentary

Without a word, Warhol settled in to use the facilities while a few of the others wandered down toward the seashore. When he came out of the bathroom, I discovered a residue of white powder on the toilet seat. Assuming it must be cocaine, I snorted the stuff up. I’d never tried it before, having only done a bit of pot or acid by this time, but yearned to fit in. Duly fortified, I headed off to the beach.

I immediately spotted Nico, which wasn’t difficult. She stood out from the others like a Viking figurehead at the prow of a galleon. Her platinum hair fell straight to her shoulders, framing a perfect face as pale as milk. Both being sun-shy, we sat together under an umbrella playing with Ari, her son by French actor Alain Delon, then about four.

I found her to be surprisingly friendly, though we had little in common—I was an impressionistic all-American guitar toting hippie, she much older, a Warhol superstar from a different generation and world, having grown up in a grey war-torn Berlin before moving to Paris, a mythical City of Light that I could only dream about.

(I never, ever, would have guessed that decades later I’d be calling Paris home, making a massive television documentary about Warhol and The Sixties and his Factory People, editing Nico’s footage from ‘La Dolce Vita’ and ‘Chelsea Girls’ into the show, and remembering those days and nights in P-town, long buried in the past of another country. Remembering that I had confided to her something that I’d never told anyone.)

While we watched little Ari make a castle of sand, I mentioned that I had just found out I was pregnant. I had but a vague idea of who the father might be, having ‘befriended’ more than a few rock and folk-music folk (the words ‘groupie’ and ‘promiscuous’ were not yet part of our lexicon). Nico was so much more sophisticated, did she “know someone” back in New York who could take care of it?

She shrugged and muttered in her low guttural monotone, “Why would you want to bother with that? A child is so easy to care for.”

At this point Ari was toddling off into the surf unnoticed, so I ran after him and dragged him back, wet and howling.

“Yes,” she smiled for the first time. “You would make a good mother.”

Well, I doubted that, since I had just mindlessly snorted cocaine off a toilet seat.

She shook her head. “It’s Andy’s talcum powder, for his wig, and to fill in the pockmarks.”

A sign! Clearly, I was meant to give up drugs and get ready for a future of diapers and dusting talcum powder on a darling baby’s bum.

So that was it. Over the next nine months I went back to college in Mexico, headed to New York for a nervous breakdown, took an extended stay in Bellevue, and escaped to Lake Placid and the Sun and Ski Lodge, where I was taken in by a kind family who deserve their own story. There, I bartended (no drinking!), sang and played guitar and hit the slopes right until my son was born.

When I ran into Nico again in New York at Max’s Kansas City, I hardly recognized her, though a mere two years had passed. Her silver blonde hair had grown out a dull reddish brown, and she seemed quite stoned. ‘Hey Jude’ was playing on the jukebox over and over and I stopped at her table to say hi and tell her that I’d taken her advice, omitting the fact that I’d given the baby up for adoption after three months, worried I would look like a failure in her eyes.

She stared at me for a long moment, as if trying to focus, then nodded wearily and went back to her cigarette and I went back to the bar to hang out with Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis.

Nico spent most of the rest of her life a perpetual nomad, playing concert venues all over the world. The singer-songwriter was working on new compositions when she died a premature death on a hot dusty day in Ibiza, Spain. She had a heart attack while bicycling into town and fell by the side of the road, where she hit her head on a rock.

I’m glad I got to thank you Nico, even if you didn’t remember. You were right in a lot of ways: Kids are easy. But life is hard.

To this day I think about him and look at his picture, a beautiful boy, now hopefully a happy man.

So, Sean, you were born on April 4 in Lake Placid Hospital, just before the Summer of Love. If you can forgive me and would like to say hello, here I am.

Catherine O’Sullivan Shorr, Paris, 2015

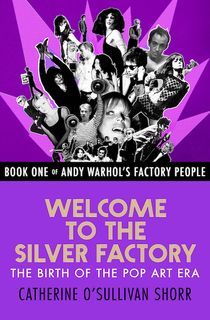

Read more about Andy Warhol and his factory people in Catherine O’Sullivan Shorr's book Welcome to the Silver Factory.

Catherine O'Sullivan Shorr is an award-winning writer, film and sound editor, and documentary filmmaker. Her published works on Andy Warhol's factory people include Welcome to the Factory, Speeding Into the Future, and Your Fifteen Minutes Are Up.