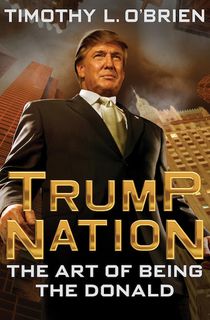

As journalist Timothy O’Brien wrote his Donald Trump biography TrumpNation in 2005, he got the full Trump experience. He flew in private jets, sat down with the mogul's wives, interviewed Apprentice contestants—and then got slammed with a $5 billion lawsuit. Trump argued that the book grossly underrepresented his net worth as $150 million, hardly the billions he claimed to have. Trump ultimately lost in court, and questions about his net worth still prevail today.

Whether you’re a Trump fan or foe, O’Brien’s “meticulous investigative biography” (The New Yorker) has plenty of juicy tidbits about the making of our president.

Related: This Kids' Book Explains Why It's So Important to Vote

Read on for an excerpt of TrumpNation, and then download the book.

My father was the power and the breadwinner, and my mother was the perfect housewife...I was never intimidated by my father, the way most people were. I stood up to him, and he respected that. We had a relationship that was almost businesslike. —DONALD TRUMP

Like so many strands of a necklace, some more worn than others and almost all of them marvels of their time, New York City’s bridges have unique identities and their own peculiar histories. Among the most elegant of them is the Verrazano-Narrows, a slender, stately crossing that took five years to build and has a 4,260-foot center span that made it, for a time, the longest suspension bridge in the world. As a direct link between Staten Island and Brooklyn, and a feeder into Manhattan, its construction had been pondered and battled over for decades before Robert Moses, the master planner of post-World War II New York, pressed the full weight of his public power and finances to the task, plowing through local opposition and upending entire neighborhoods and traditions to get it built. The Verrazano cost more than $320 million to erect, contained more steel than the Empire State Building, was spun and hung with cable wire lengthy enough to stretch halfway to the moon, and was anchored by two seventy-story towers so far apart that the earth’s curve had to be considered in their design. But it was built. This was New York.

When the Verrazano officially opened on a rain-swept November afternoon in 1964, Frederick Christ Trump, a successful developer of middle-class housing in Brooklyn and Queens, and his eighteen-year-old son, Donald, attended the dedication ceremony. As Donald would later set the scene, Othmar Ammann, the engineer who designed the Verrazano as well as the George Washington Bridge and was among the most celebrated and well-regarded bridge designers of the twentieth century, stood alone and ignored as the city unveiled his creation.

“The rain was coming down for hours while all these jerks were being introduced and praised,” Donald recalled. “But all I’m thinking about is that all these politicians who opposed the bridge are being applauded. Yet, in a corner, just standing there in the rain, is this man, this 85-year-old engineer who came from Sweden and designed this bridge, who poured his heart into it, and nobody even mentioned his name.

“I realized then and there that if you let people treat you how they want, you’ll be made a fool,” Donald recalled. “I realized then and there something I would never forget: I don’t want to be made anybody’s sucker.”

Ammann—Swiss, not Swedish—was hardly a man ignored or made a fool of in his day. Le Corbusier, for one, had singled out the George Washington Bridge for lavish architectural praise. But Donald’s recollection was telling: Someone, somewhere out there was also lying in wait and ready to make a fool of Donald Trump, to get in the way of the things he wanted to do and of the things he wanted to build. For Donald, fighting back and knowing your enemies was more than mere prudence. It was a way of being, even at the tender age of eighteen.

“You know, we live in a vicious world, and oftentimes if you don’t say it about yourself, nobody else is going to,” Donald told me, pondering Ammann’s reticence. “The lesson to me was you might as well tell people how great you are, because nobody else is going to do it.”

In a black-and-white New York Times photograph of Donald taken about nine years after the Verrazano opened, he is once again standing with his father, but this time the pair are atop a Brooklyn building with Fred’s housing project, Trump Village, visible in the background. Just off Ocean Parkway and hard by Coney Island, with the Atlantic Ocean lapping onto the shore and subway trains making aboveground stops, Trump Village was Fred’s largest development and a centerpiece of a real estate company that would eventually be valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Like most of the developments Fred oversaw, Trump Village was sturdy and efficient, comprising seven nondescript twenty-three-story towers that gave blue-collar workers and the urban middle class a first home or a stopping point on the way to something better.

In the photograph of the Trumps, both men are shot from above and are staring up into the camera with a set of blueprints spread out between them. Neither of them is smiling, and they look every bit the outerborough, first-and-second-generation German builders that they were (Fred and Donald, with a large contingent of Jewish tenants in their buildings, told the press and others for years that the family was originally from Sweden, not Germany). Donald is bundled in an overcoat in the picture, a thick, 1970s tie knotted around his neck, a pile of unkempt, light blond hair spilling around his head. He looks like a kid—no-nonsense, but still a kid—even at twenty-seven. Fred, on the other hand, looks utterly and inexhaustibly formidable. Staring out coolly from beneath a fedora, jaw set, and so in possession of himself that he comfortably sports an outrageous, polka-dot necktie, Fred is all don’t-ever-even-think-of-getting-one-over-on-me resilience and steel. Shoulder-to-shoulder, father and son occupy a moment that Donald would later recall as a favorite because it was the first time a photograph of him as a businessman ever appeared in a newspaper. Close to each other their entire lives, Donald and his father were also worlds apart.

By all accounts Fred, who died of Alzheimer’s disease in 1999 at the age of ninety-three, was a less flamboyant, less impulsive, and less combative man than his son. Stern, disciplined, devoted to his wife, and quite content to exist far from the spotlight, Fred had pulled himself up by his own bootstraps and had the self-confidence, thick skin, and money to show for it. Despite landing in the middle of high-profile business scandals in the middle of his career, Fred was well regarded within the Brooklyn and Queens nexus of self-made builders, lawyers, vendors, street-smart politicos, and fast-buck boyos who had little use for, or involvement in, the glitter and prices of Manhattan. For the most part they were neighborhood men with deep appetites; ambitious go-getters who divided their time among work, family, and political fund-raisers.

“Fred was dramatically different from Donald,” said Jerome Belson, a residential developer and lawyer who was Fred’s legal counsel for years. “He was more of a meat-and-potatoes guy. He built one-family houses and six-story buildings that were solid, usual, excellent, and with no particular flair. He was the same as other successful Brooklyn builders of that time. He didn’t stand out. He had a superb reputation. You could do it all on a handshake. His word was his bond.”

Fred ran his entire business out of a small office in one of his housing projects, at 600 Avenue Z in Brooklyn. Belson, who said he admired both Trumps, recalled that Fred “had a very dry sense of humor and he was all work.” Fred was also a survivor. His own father had scratched by as a Seattle boardinghouse owner, then peddled women and booze to Yukon gold miners around the turn of the nineteenth century before finally making a relatively comfortable living investing in Queens real estate. He died when Fred was only thirteen years old. Just two years later Fred and his mother opened a construction business in Queens, with Fred relying on his mother to sign all of the legal papers because he wasn’t old enough to do so. Fred started out building one- and two-family homes, financing them on the fly in an era when banks rarely made construction loans to start-up enterprises like his; his earnings supported two siblings and his mother. Armed with a high school education, he spent the following decades patiently expanding his business—building Queens houses in the 1920s and ’30s, navy barracks and military apartments during World War II, and large Brooklyn housing blocks for returning soldiers and their families after the war, as well as sniffing out inexpensive properties for sale in foreclosure or bankruptcy—until he ultimately had about twenty-five thousand apartment units under management.

By the time Donald was born on June 14, 1946, Fred was a millionaire. Two years later he began building a mansion for his family in Jamaica Estates, Queens, that over time would expand to nearly two dozen rooms and feature a facade boasting four Georgian columns, each twenty feet high—architectural details that would have appealed to his wife, Mary MacLeod Trump, a Scottish immigrant and homemaker with an affinity for British royal splendor.

“Looking back, I realize now that I got some of my sense of showmanship from my mother,” said Donald, whose home decorating impulses as an adult would lean toward Louis XIV on steroids. “She always had a flair for the dramatic and the grand. She was a very traditional housewife, but she also had a sense of the world beyond her. I still remember [her] sitting in front of the television set to watch Queen Elizabeth’s coronation and not budging for an entire day. She was just enthralled by the pomp and circumstance, the whole idea of royalty and glamour.”

In the mid-1980s Donald, aided and abetted by architectural legend Philip Johnson, contemplated building a sixty-story Manhattan condominium called Trump Castle that featured golden, crenellated turrets on its roof, as well as a moat and a drawbridge. Even Fred, who scoured his construction sites looking for ways to cut costs, sprayed for insects himself to save money, and plucked unused nails from the ground and pocketed them for future use, occasionally indulged in a dose of Anglophilia. Whenever Fred did so, it served a direct business purpose: bestowing a patina of proper British respectability on his middlebrow projects and making them a more appealing sell to prospective tenants and buyers. So some of his apartment houses wound up with names like Sussex Hall and Wexford Hall, and many of the homes he built had Tudor flourishes.

"I got some sense of my showmanship from my mother...She was just enthralled by the pomp and circumstance, the whole idea of royalty and glamour."

Fred also embraced flashy public relations early in his career, lofting balloons over Coney Island that contained $50 discount coupons for a $4,990 house, issuing sheafs of press releases extolling the amenities at his projects, billing himself as “Brooklyn’s Largest Builder,” and maneuvering onto a national best-dressed list alongside Dwight Eisenhower and Winthrop Rockefeller—heady company for a man who lost his father at a young age, never advanced academically beyond high school, and scrambled to make ends meet in his early years.

But Fred eventually started to snare unwanted attention, and a series of public setbacks would make him publicity-averse for the rest of his life.

When Fred began taking aim at New York’s booming, post-World War II housing market, most successful builders relied on political connections and large-scale loans if they wanted to make it big. Local politicians helped lay the groundwork by granting zoning variances and land use approvals. They also were conduits to the federal government in Washington, which in turn delivered large mortgage loans, the mother’s milk of the building community. As much as Fred was self-made, he never would have become as wealthy as he did without having participated in an innovative public-private construction partnership administered at the time by the Federal Housing Administration. To jump-start efforts to meet a massive and unmet demand for housing, developers submitted building proposals and mortgage applications to the government, the FHA loaned the money, workers got construction jobs, up went apartment complexes and houses, and working-class tenants and buyers got a home. Everybody won. But some, apparently, wanted a little bit more for themselves, and in 1953 Congress launched hearings into possible fraud in the FHA program.

Federal investigators discovered that a former FHA official had approved loans to developers of 285 housing projects that far exceeded construction costs. In exchange for at least $100,000 in kickbacks, the official allowed developers to hang on to about $51 million in excess funds. Fred was subpoenaed to testify before Congress in 1954 about the financing for two of his Brooklyn projects, Shore Haven and Beach Haven. Beach Haven alone included thirty-one buildings (six stories each) and nearly two thousand apartments; it would be Fred’s largest development until Trump Village. Although Fred rarely partnered with anyone on his developments, he testified in Washington that he had brought on a brick contractor named William Tomasello as a minority partner in the Beach Haven venture. According to federal investigators, Tomasello had extensive organized-crime ties. According to Fred’s testimony in Washington, Tomasello was a ready source of construction funds at a time when Fred said he couldn’t secure them elsewhere.

Fred told Congress that he wouldn’t have built Beach Haven if he had to invest all of his own money in it because the risk was too great. He also testified that he assessed Beach Haven’s projected costs at inflated values and then held on to the extra money the government loaned him—about $4 million. Senators accused Fred of exploiting a loophole and pocketing taxpayer funds, an accusation he denied, claiming that the money was in a Beach Haven bank account and not in his wallet. The politicians also said Fred siphoned off about $1.4 million from Shore Haven accounts that he improperly classified as dividends. Fred, using a defense that other builders deployed, said he was entitled to extra funds left over on his projects as compensation for both the financial risk he bore as a developer and for cost savings he achieved through careful budgeting. But the Senate labeled the testimony of hundreds of builders who appeared before Congress—including Fred—as “outright misrepresentation.”

Fred was never charged with any wrongdoing in connection with the hearings, but the FHA subsequently banned him from participating in future projects. Fred avoided the media after the FHA hearings, rarely showing an interest in courting publicity. But several years later his political dealings in Brooklyn would land him in newspapers again.

A pivotal figure in Fred’s real estate career was Abraham “Bunny” Lindenbaum, a Brooklyn attorney, fund-raiser, lobbyist, and political macher who enjoyed exceptionally close ties to City Hall. In the early 1960s Lindenbaum was a member of the City Planning Commission, the New York agency responsible for overseeing zoning and land use regulations in a city where fortunes were made and lost in real estate, and his client list was a roster of prominent New York developers—including William Zeckendorf, Peter Sharp, William Kaufman, and Fred. At a September 1961 fund-raising luncheon that Lindenbaum arranged for then Mayor Robert Wagner, most of Lindenbaum’s clients, including Fred, pledged money to the Wagner campaign right on the spot. Fred offered to chip in $2,500. When the lunch drew press scrutiny, Wagner initially said he did not know everyone at the meal.

“How can the Mayor deny that he knew the identity of the builders and contractors doing business with the city when Fred Trump, one of the sponsors of the Coney Island housing project, appeared before the Board of Estimate in the Mayor’s presence with Lindenbaum as his attorney?” one city official asked reporters the next day.

The ensuing public outcry about the lunch and what was perceived as a seamy mix of politics, money, and access forced Lindenbaum to step down from the City Planning Commission and gave Fred his second lesson in the dangers of overexposure.

Fred’s last large development was Trump Village, an urban renewal project that broke ground in 1961 and would include its own shopping center and thirty-seven hundred apartment units when it was completed three years later. Fred, who prided himself on bringing projects in “on time and under budget” (a mantra Donald would later adopt), finished Trump Village eight months ahead of schedule and for $5 million less than its original projected cost of $55 million. But the scale of Trump Village—seven buildings, twenty-three stories each—was far greater than anything Fred had undertaken before. After just two of Trump Village’s seven buildings were under way, Fred became overwhelmed by the project’s logistics. He only managed to complete the project after securing help from one of New York’s premier builders, the HRH Corporation. In the end Trump Village bore Fred’s name and he reaped most of the profits from the site, but he didn’t build it.

Trump Village was completed in the fall of 1964, at almost exactly the same time that Fred and Donald attended the opening of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. A little over a year later Fred found himself in front of another investigative committee, this time a New York State agency probing financial shenanigans at Trump Village. Like Beach Haven, Trump Village was publicly financed, and investigators trotted out familiar charges against Fred: owning a smorgasbord of companies that leased or sold equipment and services to Trump Village for usurious sums, banking excess funds from the mortgage that the state bestowed upon him, and channeling dubious project-related fees to Bunny Lindenbaum. Fred disputed these accusations and was never charged with any wrongdoing. But he left the hearings with his reputation tainted, and he never built another publicly financed property again.

Over the following years, Fred purchased distressed properties, bought thousands of apartments outside New York, tended to his mushrooming fortune, and patrolled his Brooklyn and Queens developments on Saturday and Sunday afternoons in a navy-blue Cadillac with customized license plates bearing his initials, FCT. For his part, Donald, in the years just before the opening of Trump Tower turned him into a business celebrity, would tool around Manhattan in a chauffeur-driven Cadillac that boasted customized DJT plates. Like father like son, though during Donald’s early years the pair often clashed, and as he matured he and Fred became increasingly competitive. Through it all, however, they remained devoted to each other.

“We had a great relationship,” Donald said of his father. “He was not an easy guy to have a great relationship. He was a tough guy. But we just had a great relationship.”

Donald was the fourth of five children and the second of three boys. Fred and Mary Trump raised their children to respect a dollar. Donald, a golf fanatic, grudgingly had to play at a public course when he was a teenager, and his father refused to buy Donald a pricey baseball mitt, telling his son he had to do chores and earn money to pay for the glove. Still, the Trumps managed to cruise Queens in Rolls-Royces and Cadillacs, hardly standard-issue automobile fare for most New York families.

“Fred Trump used to drive around in this Cadillac stretch limo,” recalled Robert Koppel, a neighbor and one of Donald’s contemporaries in Queens. “He would always wear a dark suit, like he was a millionaire impersonating a chauffeur. And sometimes you would see Donald riding in the back of the car.

“This was at a time that you wouldn’t see that many limos. It was an odd sight to see someone drive their own limo,” added Koppel. “Fred Trump was well known in the neighborhood. He was an eccentric.”

The Trump clan also followed the power-of-positive-thinking teachings of the Reverend Norman Vincent Peale, who preached at Manhattan’s Marble Collegiate Church. Among the Reverend Peale’s teaching tools were a radio show, best-selling books, and a magazine featuring inspirational success stories that he targeted at businessmen and published with financial backing from Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey and Gannett newspapers founder Frank Gannett. The Reverend Peale later presided over Donald’s marriage to Ivana Zelnicek, and as an adult Donald would accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative, latch on to the affirmative, and never mess with Mr. In-Between. “The mind can overcome any obstacle,” Donald said. “I never think of the negative.”

For his part the Reverend Peale, who died in 1993, had rather unusual insights into the budding entrepreneur’s character. Donald, the minister once said, was “kindly and courteous in certain business negotiations and has a profound streak of honest humility.”

Donald told me that he grew up in a warm, close-knit household, but that it was also a highly charged, competitive home and his father was often away on construction sites; if the boys wanted time with their father, they joined him on the job (the girls stayed at home with Mom). Summer vacations found the Trump boys collecting rents for their father or lending a hand on one of his projects. Donald’s older brother, Fred Jr., wilted under his father’s expectations. He frequently quarreled with Fred Sr., decided to become a pilot rather than join the family business, and died of a heart attack and alcoholism at forty-two. “My brother didn’t have a hunger for business, and he didn’t do well at it,” said Donald, who became a nonsmoking teetotaler. “I was devastated when he died.”

Trump in 1964, wearing his private boarding school uniform.

Photo Credit: WikipediaDonald’s younger brother, Robert, followed him into the business and later oversaw his father’s real estate portfolio at the end of Fred’s life. One sister, Maryanne, became a federal judge. Another, Elizabeth, became an administrative assistant at a bank. In his early years Donald became a serial spitballer. He boasted in The Art of the Deal about giving his music teacher a black eye—as a second grader—and he kept his high jinks at a fever pitch right up to junior high school.

“He was a brat,” said Donald’s sister Maryanne Barry, to whom the developer remained close his entire life. “He admits it. He was on the tough side.”

Fred, who once described prepubescent Donald as “rough and wild,” was not one to tolerate life’s headaches for very long. He shipped Donald off to the New York Military Academy when he was thirteen.

“I was very bad. That’s why my parents sent me to a military academy,” said Donald. “I was rebellious. Not violent or anything, but I wasn’t exactly well behaved. I talked back to my parents and to people in general. Perhaps it was more like bratty behavior, but I certainly wasn’t the perfect child.”

Military school was a wake-up call for the problem child. “They used to beat the shit out of you; those guys were rough,” Donald recalled. “If a guy did today what they did then they’d have them in jail for twenty-five years. They’d get into fights with you.

“They’d go pow! And smack you. And you know, all of the sudden a spoiled kid is saying, ‘Yes, sir!’”

Leyland Sturm, a 1957 NYMA graduate, said that no one, regardless of how wealthy his family might be, got an easy ride at the school during Donald’s years there.

“Hazing was routine. When you’re a plebe up there it’s run almost like West Point,” said Sturm. “You’d carry the cadets’ laundry, shine their shoes, and get leftovers for dinner. There was a lot of hollering in your face and hitting you on your arms.”

Colonel Ted Dobias, who was Donald’s baseball coach and residential adviser at NYMA, said he was “proud to be associated with” Donald and remembered him as an excellent, disciplined athlete who hit a clutch single to win a championship game one year. He also recalled that Donald had an awareness of appearances.

“He was very conscious of how his uniform looked—he always wanted his shoes to be shiny and he wanted to look sharp,” said the colonel. “And boy, did he like to take charge.”

After military school, Donald said he became more focused academically and professionally. He spent two years at Fordham University, then transferred to the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Finance, riding out the rock-and-roll era of the late 1960s studying business. Donald said that his time at Wharton transformed him.

“I was a little spoiled because I went to the Wharton School of Finance. And somehow, when you go to Wharton, you don’t go back,” Donald told me. “It’s not a knock at Queens, because I love Queens and I love Brooklyn, I had a lot of good times there. You go to a school like that and you do well at the school and you know, somehow you want to break out of that mold. I think it brought me into a different world.

“I learned more from my father than anyone,” Donald added. “He never wanted to come into Manhattan because it wasn’t his thing. He was a wonderful negotiator and he couldn’t understand how you could buy a foot of land in Brooklyn for 25 cents and yet you had to pay $1,000 for a foot of land in Manhattan. It wasn’t his thing and it was the best thing that ever happened to me. If my father came into Manhattan, he would have been successful and you probably wouldn’t be talking to me right now. You understand that? In a certain way, I would have been a son of a guy who made money. Making money in Brooklyn isn’t the same; it’s different.”

"He was a brat...He admits it. He was on the tough side."

All of this eventually added up to Donald’s break with Queens and Brooklyn, but it would be a long time before he did deals without his father’s guidance and financial support. Donald depended on Fred’s connections to launch his first deals, and despite any larger aspirations Wharton unleashed in him, he returned home after his graduation in 1968—and he worked there for about five years before he tried to strike out on his own into Manhattan. Fred’s days of building big housing projects were well behind him by this point, and Donald’s chores were not high end: Other than scrambling to structure a few real estate investments for his father, he said he went door-to-door in Brooklyn collecting rents, often accompanied by thugs who could protect him if tenants got nasty.

Pounding the pavement around projects isn’t the stuff of budding billionairedom, and Donald’s imagination constantly took him elsewhere.

“My father understood how to build, and I learned a lot from him. I learned about construction, about building. But if I had an edge over my father, it might have been in concepts—the concept of a building,” Donald later told Playboy magazine. “It also might have been in scope. I would rather sell apartments to billionaires who want to live on Fifth Avenue and 57th Street than sell apartments to people in Brooklyn who are wonderful people but are going to chisel me down because every penny is important.

“You have to be comfortable with what you’re doing or you won’t be successful,” he added. “I used to stand on the other side of the East River and look at Manhattan.”

Donald lived in Queens until 1971, when, at the age of twenty-five, he ventured across the East River and moved into Manhattan for the first time. He rented a one-room apartment on the sixteenth floor of 196 East 75th Street, near Third Avenue, and commuted to Brooklyn where he continued to help manage his father’s stable of apartments.

“Moving into that apartment was probably more exciting for me than moving, 15 years later, into the top three floors of Trump Tower,” Donald wrote in The Art of the Deal. “I was a kid from Queens who worked in Brooklyn, and suddenly I had an apartment on the Upper East Side.”

For most of America, looking in on New York from the outside through the glass lens of their television sets, Manhattan in the 1970s was The Odd Couple’s Manhattan, where Oscar and Felix avoided Central Park because that’s where you got mugged; it was All in the Family’s Queens, where Archie Bunker dug in his heels; it was Welcome Back Kotter’s Brooklyn, where graffiti-laced subways delivered an ethnic hodgepodge of lovable misfits to a gritty high school. For Americans who went to the movies, New York was Gene Hackman busting a heroin ring in The French Connection; Robert De Niro stalking a politician in Taxi Driver. For Americans reading newspapers, New York was a city on the verge of financial collapse, unraveling amid blackouts and street crime. For Donald, a trust-funder with money to play the club scene, New York in the early to mid-1970s was a great place to get laid.

Donald frequented Studio 54 in the disco’s heyday and he said he thought it was paradise. His prowling gear at the time included a burgundy suit with matching patent-leather shoes.

“What went on in Studio 54 will never, ever happen again. First of all, you didn’t have AIDS. You didn’t have the problems you do have now,” he said to me. “I saw things happening there that to this day I have never seen again. I would watch supermodels getting screwed, well-known supermodels getting screwed on a bench in the middle of the room. There were seven of them and each one was getting screwed by a different guy. This was in the middle of the room. Stuff that couldn’t happen today because of problems of death.

“You know, it’s a whole different world today,” he added. “I remember watching Truman Capote dancing with himself in the middle, spinning around. Elizabeth Taylor … Halston. Yves Saint Laurent. They had like forty superstars in the room.”

Being in the orbit of superstars was no small matter for Donald because his imagination was, and remains, decidedly cinematic. Before heading off to college he was fairly certain that he wanted a career in show business, not real estate. He said he planned to attend the University of Southern California to study filmmaking and had already produced a Broadway show called Paris Is Out.

Alas, Hollywood was not to have young Donald.

Just before he left for Fordham, Donald helped a Manhattan entertainment lawyer named Egon Dumler find an apartment and Donald said that the attorney, impressed with the depth of his real estate know-how, convinced him that his talents would be wasted on the West Coast. Donald said the lawyer told him that real estate, not movies, was his calling.

“I thought about it and then I said: ‘You know what I’ll do? I am going to go into real estate and I am going to put show business into real estate,’” Donald recalled. “‘I’ll have the best of all worlds.’”

Want to keep reading? Download TrumpNation now!

.jpg?w=3840)