“We embraced again, we wanted to engulf each other. We had cast off our families, the world, time, certainty. Clasping her against my gaping open heart, I wanted to draw Isabelle inside. Love is an exhausting invention. Isabelle, Thérèse, I pronounced in my head, getting used to the magical simplicity of our two names.” –Violette Leduc, Thérèse et Isabelle.

It’s one of the most wretched grievances for any writer, having to mutilate your own work to appeal to a publisher and public’s agenda. It’s like having to let go of your prized possessions, for a time, or even choose favorites among your own children.

But what separates the great writers from the rest is the willingness to be resourceful with one’s annexed material and wait for the next golden opportunity to bring it out. Patience, and a strong enough confidence in the merit of one’s own work, even if the rest of the world is not ready for it. That is exactly what Violette Leduc, a twentieth-century French writer with a powerful resilient streak, did with her Thérèse et Isabelle.

It’s an honest, exposing, and highly erotic sapphic tale, one that may seem cliché by modern standards but was almost recklessly brave and enterprising in Leduc’s time. Two girls in boarding school fall deeply in love and initiate a secret affair behind the backs of their conservative teachers and relatives alike. A simple concept, and one that’s had its share of successors in modern LGBT literature.

Anna Birch’s 2020 I Kissed Alice comes to mind, as does Jane B. Mason’s Without Annette. Even in Leduc’s own era, the idea of boarding school sexual encounters was latched onto as a topic by pornographic writers. Anais Nin did it when she was hurriedly stringing together stories with her friends for a rich private collector, and these would later appear in her assembled collections of erotica. Dorothy Strachey’s single novel Olivia, about a passionate romance between a female student and her teacher, was published in 1949.

But Leduc’s output was more than just a racy writing exercise for money or early pre-Pride era credit in subversive women-loving-women literature. It was a full, meticulously detailed, shockingly intimate memoir of her own early lesbian experiences with a girl that she, in a way, never stopped being infatuated with, long after they had separated. The memories haunted her, and so they made their way onto paper and then in print.

Leduc was obsessed with her own difficult past, as her repertoire of autobiographical texts reveal, and somehow, she found the courage in a post-war Europe to make her past so well-known in the literary world that she would earn a reputation as a miner, not a minor, writer. One that scrapped her memories bare for her art, and saw her labors rewarded with due recognition.

Her writing also doubled as a therapeutic process. A way of reorganizing her disturbed mind, cluttered as it was from years rife with childhood neglect, low self-esteem, and of course, lost loves. “Memories are comfy too, they are swaddling bands, they wrap you up warm like a mummy. What moment is there in life that is not already a memory?” she pointedly wrote in her The Lady and the Little Fox Fur.

She followed the lead of her close friend and mentor Simone de Beauvoir, the unwaveringly active mind behind The Second Sex and The Mandarins. A chance encounter in a Parisian cinema lineup launched this productive partnership, though Beauvoir was likely not prepared for the heavy emotional baggage Leduc brought into the relationship. Leduc was, reportedly, a very challenging person to get along with, and tended to become desperate and clingy towards those she developed any sort of affection for.

Nevertheless, Beauvoir made good on her promises to help her troubled and cash-strapped acquired acquaintances and acted as the capable midwife to deliver Leduc’s loud, disruptive, and genius books into the world. Leduc confided in Beauvoir about everything: her scandalous beginning as the illegitimate offspring of a wealthy man and a servant, her lesbian love affairs while attending boarding school at the Collège de Douai, her failed short marriage and illegal abortion, and her unrequited love for Maurice Sachs, a fellow writer who also mentored her but rejected her romantic advances. Beauvoir encouraged her to write about all of it, and Leduc did.

Leduc bravely complied everything about her turbulent love life into a 1955 novel Ravages, which was taken up the prominent French publisher Gallimard. However, the editor got cold feet about the first one hundred and fifty pages of the novel, which depicted, without restraint, Leduc’s loss of virginity with her classmate Isabelle P.

It was considered too much of a risk for the publishing house, who regarded it as too controversial. Leduc was forced to accept a hard compromise. The first section of the book would be axed, but she would be allowed to include her candid passages about her abortion, a major step forward in the French feminist movement’s campaign to make the issue public. But Leduc wasn’t satisfied with presenting her life only partially. She never trashed the pages about her beloved Isabelle but rather held onto them until a more convenient time to bring them out came along.

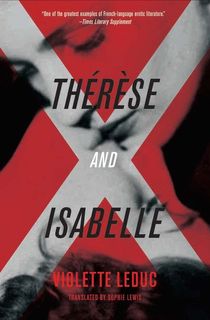

It did come along, eventually. By 1966, the editors of Gallimard seemed to have grown spines and they released the deleted scenes of Ravages as an entirely separate book, Thérèse et Isabelle. In this version, Leduc expands the text, and her two thinly disguised schoolgirls get to fully explore their first love with each other without ever having to move on to another storyline.

This would be the book that would really solidify Leduc’s standing as an erotic queer writer, and it places second in notoriety only to her mammoth 1964 memoir La Bâtarde. Its potential as a film was quickly recognized by American director Radley Metzger, who in 1968 brought out a cinematic version of Thérèse et Isabelle starring Essy Persson and Anna Gaël as the titular amorous girls.

The book is now considered an LGBT classic and a 2015 edition was released by The Feminist Press to honour Leduc’s contributions to lesbian visibility in literature. Leduc has secured her place in history as an author who wrote about real love and not just a sanitized and palatable “romantic friendship,” as many had done before her. She, as a woman, loved Isabelle completely. Is there any denying the true heartfelt validity of this prose?

“I contemplated her, I was remembering her in this present, I had her beside me from last moment to last moment,” wrote Leduc in the novel, reminiscing. “When you are in love you are always on a railway platform.”