One of the most acclaimed British authors of the 20th century, Lawrence Durrell was born in India to colonial parents in 1912. He spent the first 11 years of his life there, after which he was sent to school in England. By the age of 23 he was married, had published his first book, and was living on the Greek island of Corfu with his family, including his youngest brother Gerald Durrell—who would eventually become a prominent author in his own right.

It was there that Durrell read Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. He wrote to Miller to tell him how much he had enjoyed the book, beginning a chain of correspondence between the two and what would become a decades-long friendship. In 1937 Durrell went to Paris to meet with Miller and Anaïs Nin, and from there, the rest is history. Durrell became a prolific writer and an avid traveler, and supported this lifestyle by working in the Foreign Service of the British government.

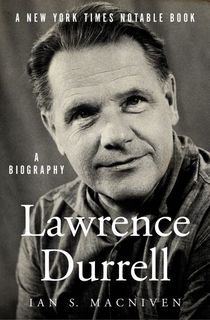

Between 1957 and 1960 Durrell published the four books that made up The Alexandria Quartet, which would become one of the defining works on his career. From that point on biographers began approaching Durrell about writing his biography, but he demurred until 1979, when he finally agreed to let Ian S. MacNiven take on the task.

MacNiven already knew Durrell before he passed in 1990, but he also put a tremendous amount of research into the biography, and it shows—over 20 years MacNiven interviewed hundreds of people who knew Durrell, published an edited book of letters between Durrell and Henry Miller, and travelled to all but one of the many locations where he had lived. The result is an incredibly intimate portrait of Durrell’s life.

Below, read an excerpt from the prize-winning biography.

Preface

To understand Lawrence Durrell one must go to India, physically if possible, but otherwise at least in the imagination. One must feel the damp heat of Calcutta and the chill dawns of the high Punjab, must experience the friendly, pungent crush of the bazaars and hear the monotone trumpets of the Buddhist temples and see the creatures of the Terai forest. Above all, one must enter the vanished colonial world of the Durrell family. This world, grafted on to the trunk of India like a strange fruit united to a hospitable but overwhelming tree, instilled in Larry both pride and guilt: pride in the practical skills of his family, guilt because he could not assume a place in the machinery of Empire. He saw the role that was waiting for him, and turned away. Loving India, he felt that he belonged to it, yet he was estranged by his otherness: a white child among brown playmates, predestined to a master’s position that he did not want. Even within his family, he soon discovered that he thought differently, precociously. His was not to be an unquestioning acceptance of the pattern of the more prosperous colonials: a childhood pampered by servants and followed by education abroad, the return as a master, with long hours of arduous work, whisky at the club and a small grave somewhere in the vast land. He learned to conceal his rebel thoughts, and this made him lonely while still at home, a foretaste of the loneliness that would haunt him for the rest of his life. None the less, Larry would carry with him into his lifelong exile the psychic burden of his ancestors, their aspirations and accomplishments and defeats. What he rejected outwardly remained alive inside: the lonely colonial child shadowed the cosmopolitan writer.

Durrell was early sensitive to the ‘spirit of place’, but Tibet and India would evolve into a state of mind more than a geographic locus for him. The Alexandria Quartet, the work that would gain him an international readership and fame, Tunc and Nunquam, the novels that would lose for him some of his audience and his American publisher alike, and The Avignon Quintet, the magisterial final sequence that would puzzle some of his most loyal friends, are none of them set in the Orient. And yet, and yet … India remains the fiery shade behind Durrell’s thought and work. If he succeeded—and Durrell himself was never quite sure that he had—his life’s work will come to be seen as a keystone, a clou, a bridge linking the human physical and spiritual centres of East and West, a passage from India to the British homeland of his ancestors and back east again.

Related: An Interview with Manju Kapur, Bestselling Indian Author

Golden Temple, Punjab, India | Unsplash

Photo Credit: Mohd AramLarry’s own passage would be uneasy and eventful: the bitter experiences of schoolboy exile and early loss, his discovery of Greece, the thrill of Paris in the 1930s and the shock of war, adventures in many places and with many women, the years of doubt and uncertainty, the public triumphs, the unrelaxing and unforgiving daemon driving him until the end. Durrell’s ancestry and upbringing gave him a language and a tradition; India gave him a sense of otherness; England nearly broke him to harness; Greece freed him again; Egypt gave him his major subject. War, passion, divorces, disappointment, self-doubt, the temptation to suicide scorched him. Out of Durrell’s drive and tensions and experiences came a range of hard-won novels, volumes of poetry, plays and non-fiction.

‘Thirteen is my lucky number,’ Lawrence Durrell liked to say, and at his favourite Hotel Royal in Paris he invariably reserved Room 13. It was a way of challenging Fate, of asserting that he was not bound by superstitions and accepted beliefs, while at the same time admitting to a quaint fetish. Durrell also dallied with astrology, espoused acupuncture, and played with the symbolism of the Tarot, notably in The Alexandria Quartet. He was fascinated by the hard sciences, including physics, astronomy and medicine, and especially by the great soft one, psychology. He could perform splendidly, whether for a single interviewer or, rarely, before a large audience, yet he was a humble, shy and intensely private man. Many contradictions were at home in Durrell’s short frame. These contradictions challenged me as his biographer, and I struggled for most of the writing of this text to interpret his life in twelve chapters. Somehow, the story refused to fit; and besides, twelve seemed too biblical a number for the author of Monsieur: or, The Prince of Darkness. Thirteen it had to be. Here, then, is Lawrence Durrell in thirteen acts.

After writing a first novel about a boy with an Indian childhood that was clearly autobiographical, Durrell strove to distance his fiction from his own life. Yet, latterly, he threatened repeatedly to write an autobiography, or else to bring out a volume of photographs based on his disordered piles of prints and negatives. This book is in part an attempt to accomplish what Durrell never found time for: to tell his story in his own words. Thus, I have depended heavily on Durrell’s interviews, letters and published work, adding links and correctives where necessary.

Related: 15 Powerful Books About Immigration

Once, when Durrell was accused of remembering things ‘vividly’ but inaccurately, he replied to his interviewer, ‘I think that’s the juggling quality I have.’ An astrologer had told him, he recalled, that he was characterized by ‘evasion and flight and non-comprehension of what I really am and what I really feel’, and Durrell had to agree that, as an ‘illusionist’, he often baffled himself. ‘I am the supreme trickster,’ he cheerfully admitted. However, in addition to his elusive quality, Durrell was a self-ironist with an enormously developed sense of play. Turning a suddenly guileless blue eye on the interviewer—who was doubtless congratulating himself on having pinned a label on to Durrell—he continued: ‘But fortunately I’m not to blame. I gather it’s something to do with the Fishes, to which I belong …. Pisceans are a bunch of liars, and when you add to that an Irish background, you have got some pretty hefty liar.’ This too was disingenuous: Durrell was no habitual liar, and he was usually touchingly eager to please, to give truth-value to those who sought him out. Only, the illusionist and the joker did indeed reside within, and he was too good an actor to signal his mercurial shifts from facts as he saw them to what he called ‘reality prime’, from truth to the essence of truth—or to devilment.

Durrell’s shyness made him shun autobiography: he rarely spoke in detail about himself, except as artist, and although he filled countless notebooks, he did not keep a regular diary. He was most consistently personal and truthful in his poetry, but his habit of evasion often made him disguise the personal even there. None the less, he distilled the sensation points of his life in his poetry, and some of these crises are heralded, as Durrell would have said, in the passages chosen for chapter headnotes.

This book springs from Durrell’s contradictory nature. He was a very private person who adored good company, a recluse who had many friends and who loved many women, a spiritual man who was a sensualist. In the 1950s he was so protective of his privacy that when the publication of his and Henry Miller’s letters was proposed, he suggested that only Miller’s be included in the volume. As soon as The Alexandria Quartet appeared, Durrell began to be approached by would-be biographers. His answer was always No.

Related: 10 Captivating Writer Biographies

Lawrence Durrell on his boat.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the British Library's modern manuscripts collection.I had corresponded at widely spaced intervals with Durrell, beginning in 1970, at first mainly about the archive of his manuscripts and books that had been purchased by Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, and had visited him in France in 1975. Then in 1979 he asked me if I would like to begin assembling the material for an eventual biography, to appear after his death. He had finally resigned himself to the fact that eventually someone would write his life story, whether he wished it or not. His friends were dying off, he said, and someone might as well start collecting information. With my wife—companion and partner in my researches throughout—I began a series of visits to Durrell in his small Languedoc town of Sommières. In 1986 he spent two weeks with us in New York and Pennsylvania. He provided us with addresses of his family and of many friends, and we travelled to Bournemouth, to Greece, to Alexandria, to Yugoslavia, to Cyprus, to India. Durrell demanded no oversight of the biography and made no conditions, other than not wishing publication during his lifetime. Even this he dropped towards the end, saying, with a touch of malice, ‘You have found out all there is to know about me—why don’t you write the damn thing?’

To begin with a certainty: there is only one pronunciation of the family name. Durrell rhymes approximately with squirrel; it is only a shade off a monosyllable, but is melodious. It is a stubby name, fittingly like his physical form. As I began the actual writing, Durrell’s first name intruded itself more and more insistently. Durrell-the-writer had a comfortable fit, but ‘Durrell’ sorted oddly with Larry the son, brother and centre of a circle of friends. There was also the ebullient and imposing shadow of the Other Durrell, Gerald Malcolm, Gerry, zoologist and best-selling author. Larry Durrell invited informality while maintaining his privacy: from his tightly shuttered core he would give the cue to the personality required for each occasion—Lawrence Durrell inscribing books at Hatchard’s in his beautiful hand, Durrell as Director of Information Services on Cyprus, Larry the bon vivant, companion, lover. His books seem to me to have emanated from a source that could better be called Larry than any other part of his name. A more formal biography can Durrell him; the man himself preferred to be Larry.

The biggest obstacle that I encountered in researching this book was Larry Durrell’s humility. He evinced very little interest in speaking about himself, except occasionally to spin fanciful versions of his past. I soon discovered he believed that the only important side of his story lay in his writing. He appeared to have scant concern for his reputation, yet he seemed almost naïvely grateful for any sincere attempt to understand his work—even when he disagreed: ‘Oh, thank you for your brilliant and solacing study’ was one of his standard responses to scholars. Perhaps he really meant it.

Corfu, Greece | Unsplash

Photo Credit: Mikuláš ProkopThe details of Lawrence Durrell’s life—his boyhood in India, his schooling, his wives, children, friendships, lovers, exploits—tended in his stated opinion to fade into an all-encompassing nebulosity that he often described with one word, ‘boring.’ ‘Surely that’s part of the record,’ he would answer reproachfully to questions about his private life. He pretended to believe that some Recorder had kept a log of his movements and affairs, impersonally, along with all other lives, and that he had been simply ‘lucky’ in managing to write a few novels and poems and in loving a number of beautiful women.

Once, in exasperation at the contradictions that I was unearthing—and sometimes hearing from the Durrellian lips—I said, hoping to badger him into a single version of the truth, ‘Larry, I know what I’m going to do: I’ll write your life as a quartet, with four versions—and let the reader choose.’ I should have known better. ‘Yes’, he replied with his most enigmatic smile, ‘why don’t you? What a splendid idea!’ I retreated. I made choices.

Related: Family and Fireflies: Anecdotes from the Real-Life Durrell Family

Shortly before Larry’s death in 1990, I sent him the chapter dealing with his discovery of Corfu. We spoke at length on the telephone, and he cleared up a few details. I looked forward to future consultations on the text. It was typical of his self-effacing side that he would elude me in this: two weeks later I picked up the ringing phone to hear that Larry was dead.

This, then, is one version of the life of Lawrence Durrell, composed with a good deal of love, an affection that has not compromised what I hope is an unflinching portrait of Durrell entire. I have presented as many facets of his character as I could catch, and have attempted to link the development of the man with the evolution of the artist. He did not believe in the existence of the discrete ego, the unique and indivisible personality, and this he exemplified in his own nature. I do not pretend to have written the definitive word. How could I?

Ian S. MacNiven

The Bronx, 1996

Download Lawrence Durrell to keep reading.

Lawrence Durrell

Elegant and meticulous, this authorized biography of the author of such literary works as The Alexandria Quartet and The Avignon Quintet is a belletristic treat. (Kirkus Reviews)