It is fitting that fabulism tends to defy any direct definition. Fabulism, in essence, is the act of defying any genre constraint. The term has its fairytale and fable roots, and yet it continues to cause confusion when someone uses it to describe a story. Perhaps the most general of definitions would be, “where literature gets weird.”

If one desires something more specific, fabulism can be traced out as a narrative that contains magical realism, slipstream, science fiction, horror, and/or surrealism as traits. The best fabulist narratives tend to blur the line between one or more of these traits. At the center of fabulism is mystery. Readers are attracted to and therefore read a fabulist tale because they want to know what it is. The defiance of clear definition is a clever choice to stand tall and let the story speak for itself.

Related: 10 Books That Push Boundaries

So what if the story tends to be exceedingly weird? Maybe this isn’t enough of an explanation of what fabulism is. The genre truly defies by nature, it’s rebellious and individualistic; it likes to stand tall and stand apart. The best way to define fabulism is by example.

The following books are examples of fabulism at its best—unique, weird, and wonderful.

The New Wave Fabulists

This anthology edited by prolific author Peter Straub for the literary journal Conjunctions is a perfect launchpad for discovery of this vibrant genre. With stories by heavy hitters like Neil Gaiman, China Miéville, Elizabeth Hand, and Kelly Link, Straub has gone to great lengths to select stories that reveal how science fiction, horror, mystery, and fantasy, when turned on their side and transformed by way of innovating beyond typical tropes and genre designations turns into an unrecognizable marvel, i.e. fabulism.

The volume also has a series of essays by John Clute and Gary K. Wolfe that help explain the ever-evolving genre of fabulism.

Magic for Beginners

When people ask for one recommendation that displays masterful fabulist fiction, I go right for Kelly Link’s work and this collection in particular. In nine stories, Link traverses wide terrain.

In “Stone Animals,” the haunted house trope is upended when a family moves in and discovers that everything about their lives unravels, becoming haunted. The image of a horde of rabbits lingering on the house’s front lawn each evening only adds to the majestic oddity.

“Some Zombie Contingency Plans” is unassuming at first but soon becomes a moody story of a thief, a homeowner and her brother who hides under the bed. Link takes domestic terror and dark fantasy and blends it into a palpable demonstration of modern fabulism.

The Dark Dark

Hunt’s dark collection of stories takes fabulism into far more horror-laden territory. The breadth of the collection is a true testament to a fabulist’s ambition to innovate and tear apart the common structures by way of finding something new. The Dark Dark is, like Link’s aforementioned collection, a demonstration of the genre. Here we witness all kinds of transformations and among the shadows.

Related: The 15 Best Horror Books—We Dare You to Finish Them!

In “A Love Story,” the protagonist battles with fidelity and loyalty with her husband. Claiming that she adores and loves him, she systematically manages to turn him into the opposite of a lover, a stranger and intruder in their home.

One of the more interesting experiments in the book are two stories called “The Story Of and “The Story Of Of” respectively. The first tells a story only for the second one to answer the mysteries of the first, recursively riffing on each other. Hunt demonstrates how fabulism can be as metaphysical as it wants.

The Bus Driver Who Wanted to be God

Man, Etgar Keret is funny. Talking about both “Ha ha” funny and that brand of funny that tickles one’s intellect. You may know his work from the films Wristcutters: A Love Story and $9.99, both films adapted from stories in this volume. Keret is indeed a fabulist in that he defies normalcy while still working from a point of the mundane.

Related: Laugh-Out-Loud Funny Books for Adults

For instance, the source material for Wristcutters is a story called “Kneller’s Happy Campers,” which is about a young twenty-something at the peak of a breakup, so depressed that he slits his wrists. Yup, suicide. Bleak. And yet, Keret takes the dark and adds some dark humor: The man doesn’t die. Instead he wakes up in the same place, only it’s a little different, everything just a little bit worse. And nobody there can smile or feel anything but a low-level blasé. Keret does this with the entire gamut of everyday life’s concerns and curiosities.

The Famished Road

The Booker Prize winning novel The Famished Road stands the test of time and has truly become one of those touchstones of magical realism. But it’s also an extraordinary example of fabulism too!

Readers are introduced to Azaro, an abiku or spirit child, that exists between life and death. The inherent tragedy of being in an in-between state and how it allows for Azaro to see beyond time and memory affords both Okri and the narrative with so many ways to bend fantasy and expectation. It’s truly an epic novel that also functions as a journey of discovery for those seeking to explore the possibilities of literary fabulism.

American Gods

What hasn’t been said about Gaiman’s modern masterpiece? Even if you happened to eschew reading the novel in favor of watching the television series, you already know about this one. Everyone does. So instead of focusing on the plot, let’s dive into why Gaiman’s work, and particularly American Gods, operates in the fabulist genre.

Firstly, Gaiman cleverly displaces the deities and gods typical of lore in Americana and the usual drawl of modern-day western society. Our protagonist is fresh out of prison, driving around all depressed because of his wife’s death by car accident. He isn’t acting at all like a “god” and deals with the physical and mental traumas that come with living a “normal” life.

Secondly, the gods referenced in the title area fading away, no longer as powerful due to people’s general disregard and disinterest in the folklore and legends that propelled their powers based on interest. It’s a clever take, for sure, and it’s these two important contextual changes that showcase how American Gods bends genres—literary roadtrip novel in this sense—to create a really compelling narrative fantasy.

All the Bells on Earth

Much like American Gods, the superhuman becomes normal and the normal becomes absurd. Blaylock is long known for his interesting blend of characters, narratives that sow together a wider view by way of multiple perspectives. All the Bells on Earth is him arguably at his best.

It’s Christmas season and we witness three scenes of madness—a man climbs a church tower to try to silence the bells; a person in an alley spontaneously combusts; and a businessman by the name of Walter Stebbins comes into contact with a glass jar containing the preserved body of a bluebird.

Related: 15 Dark Books for the Literarily Disturbed

It’s a crazy setup that only gets even more insane as Blaylock spins a story that showcases the ripple effect of making deals with the devil. The novel flexes its fabulist muscles by way of the balancing act of the absurd with fantastical spirituality.

One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

As someone who has always been interested in the unknown, the “apocalypse” has always been a topic of personal fascination. To think: All that we know could so quickly expire and become something else. Well, that’s the thematic crux of Lucy Corin’s collection of short stories.

Akin to Keret, Corin turns to darkness with some humor, even if it doesn’t translate as outwardly hilarious at first. In the story “Madmen,” Corin paints a picture of an America where part of reaching adolescence means choosing the madman that’ll accompany you into the perils of adulthood. It’s one of my favorites and among the best in the collection, and acts as an exemplification of her wild imagination and fabulist edge.

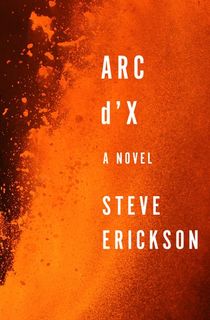

Arc d'X

Erickson has built a career on sculpting seemingly normal and depressing settings and blurring them with a surrealistic intensity that feels so very dreamlike and nightmarish. In Arc d’X, Erickson turns to alternative history, particularly America’s own history, and imagines a post-apocalyptic universe where readers travel across different periods of time to see the grave effects of our forefathers’ destruction and slavery of the land and its people.

The best way to describe it is David Lynch’s Inland Empire blended together with a History Channel documentary, and then having it be viewed four times in a row by Thomas Pynchon; the end result would be what Pynchon dreams that night. Erickson’s novel is fabulism at its most ornate and surreal.

Related: An Interview with Steve Erickson, An American Surrealist

Mr. Fox

Nowadays, Helen Oyeyemi is a literary household name. She’s gone from one novel to the next of surprising and odd and weird stories that never take you to the same fabulist place twice. In Mr. Fox, Oyeyemi brings us back to 1938 and one Mary Foxe about to visit the famous novelist, St. John Fox. They haven’t seen each other in years… but the twist?

No, it’s not some father/estranged daughter situation. More like a fabulist cross of it and writer’s block. Mary Foxe doesn’t exist. The novelist made her up. When she “visits” unexpectedly, he is once again reminded of his stature as a novelist being cruel, yet also obsessing over, his characters. It’s a really clever demonstration of getting metaphysical and fantastical.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for Early Bird Books to celebrate the stories you love.

.jpg?w=3840)