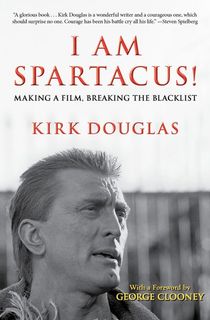

In 2012, when Kirk Douglas was 95 years old, he penned a memoir called I Am Spartacus!. As he wrote in its introduction, he had lived through “sixteen presidents, two World Wars, the Great Depression, and a score of political crises from Teapot Dome to Watergate to Bill Clinton’s impeachment for being publicly serviced in the White House.” Kirk Douglas had been witness to many historic moments—and in 1959, when he was producing and starring in Spartacus, he created some of them, too.

On top of being a masterful achievement of cinema that would become a cultural touchstone, Spartacus effectively ended the notorious Hollywood blacklist that was a byproduct of the infamous HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) trials.

Douglas, who believed the ‘50s were a time of fear and paranoia and saw how the blacklist was ruining the lives of innocent Americans, went ahead and hired Dalton Trumbo to write the screenplay for Spartacus. Trumbo was one of the “Unfriendly Ten” who had gone to jail rather than testify to HUAC, and spent a year in jail and a decade on the blacklist for it. It was a risky decision to hire Trumbo, but it was also a fitting one—the source novel Spartacus, about a slave who leads a rebellion against his owners, had been written by another HUAC defier, Howard Fast, during his jail sentence.

From heated moments with then-unknown director Stanley Kubrick to struggles with his leading lady and negotiations with the film’s other stars (Sir Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Peter Ustinov), creating Spartacus was never easy. But Kirk Douglas believed in the film, saying that “the story of Spartacus is as important today as it was fifty years ago—and two thousand years ago.” Luckily for Douglas, it was all worth it—the film was a tremendous critical and financial success, and cemented his place in Hollywood stardom.

Below, in tribute to Kirk Douglas’s death, is an excerpt from I Am Spartacus!. Though it was written 52 years after the making of the film, it’s clear that Douglas’s memory—and master storytelling skills—were as sharp as ever.

Chapter Two

“Good luck, and may fortune smile upon…most of you.”

—Peter Ustinov and Lentulus Batiatus

IN THE SUMMER OF 1950, both Dalton Trumbo and Howard Fast were languishing in dank prison cells, thousands of miles from their homes and families. Each man had to be wondering what the future had in store for him.

The fear that caused their imprisonment was still on the rise. Another round of congressional hearings aimed at Hollywood was already being planned. But, looking back on it with some distance—and I’m almost ashamed to admit it—my own life couldn’t have been much better. I was untouched by the blacklist and, frankly, I wasn’t thinking a lot about it. The world was in turmoil—a hot war in Korea, a cold war with the Soviets, suspicion and division in America—yet I was lucky. None of that was affecting me.

The big events happening in my life were all on the home front. I was thirty-three years old and married to a beautiful girl named Diana Dill, another of my classmates from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She was so beautiful that she had appeared on the cover of Life. Somehow I got a hold of a copy of the magazine while I was in the navy. I showed it to my shipmates and told them I was going to marry her.

I did and we had two wonderful boys, Michael and Joel. (Our marriage didn’t survive, but our family did. Diana and I remain good friends. My wife, Anne, calls her “our ex-wife.”)

Kirk Douglas holds up one of his children with his second wife, Anne, in the background.

Photo Credit: Globe PhotoBy 1950, believe it or not, I was a bona fide movie star. I had played everything from a boxer to a police detective to a trumpet player. Champion, my eighth film, had been released in 1949. It earned me my first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. Even the tough New York Times critic Bosley Crowther had positive things to say about me: “Kirk Douglas does a good, aggressive job . . .”

And the money! My God. I was making more money than I’d ever dreamed of. My six sisters and I grew up during the Depression era. Our family struggled every day for bread and borscht. My mother struggled every day with my father.

Home was Amsterdam, New York, a small city north of Albany. When I was growing up, it was known primarily for carpet making. If you didn’t have a job at one of the two big carpet companies—Bigelow-Sanford or Mohawk Mills—you had a hard time getting by. My father worked as a ragman, riding up and down the streets of Amsterdam collecting rags and scrap metal for resale. What money he did make often went to the saloons instead of to our family.

Now I was earning more in one year—in one picture—than my father made in his entire life.

Related: 8 Books Set in Old Hollywood

In Kentucky, Dalton Trumbo was earning only prison wages.

Just a few years earlier, he had been Hollywood’s highest-paid screenwriter at $75,000 a picture. Although he was no longer pitching projects to Howard Hawks or Victor Fleming, his eloquent voice was still being heard, at least by those who cared to listen.

During his many months alone in that tiny cell, he wrote poignantly about his confinement. He was as candid as ever. This letter was sent to his wife, Cleo:

Two days hence will be our thirteenth wedding anniversary and I have been lying here on my bunk, thinking about it . . . more and more I realize that when I emerge from here, I must make the choice of what kind of writer I want to be. I think it would be better for all of us if I returned to writing novels, with the occasional foray into theater. It will probably take years to recover from the blow dealt by the blacklist.

Sadly, he was proven right.

Howard Fast was released from prison on August 29, 1950. Never a heavy man, he was now twenty-eight pounds lighter. Like Dalton Trumbo, Fast had been thinking a lot about his writing career. But unlike Trumbo, never for an instant did he consider changing it.

He had always been a novelist. He was determined to remain one.

Fast spent the next nine months writing what he hoped would become his magnum opus—a novel he called Spartacus. Plunging himself into the research, he made an extensive study of slavery and the methods of imprisonment practiced in ancient Rome.

He did this even as his own freedom as an American citizen was being systematically reduced and restricted. All in the name of keeping America “safe.”

Even when Fast finished serving his sentence and was technically a “free man,” his political views still cost him. He was banned from speaking on college campuses. He was under constant surveillance. J. Edgar Hoover took a personal interest in his activities—Fast’s FBI file grew to over eleven hundred pages.

When he wanted to travel to Italy to do primary research on the life of Spartacus, Fast was denied a passport. It would be ten years until he was able to obtain one.

Despite all these obstacles, Howard Fast finished Spartacus in June of 1951.

Writing the book was the easy part. Selling it was not. The blacklist had found its way into the publishing business as well.

Related: The 8 Most Controversial Books Ever Published

Fast sent Spartacus to Little, Brown, the respected New England literary house that had published three of his previous books. After reading the manuscript, the editor was excited and eager to take it on, but a few weeks later, he called Fast back to say the house was passing. Fast soon found out why. As it happened, an FBI agent had been sent to Boston to meet with the president of Little, Brown. Privately, he had “advised” him not to publish anything written by Howard Fast. If he did, the agent went on to say, action would be taken against his company. These instructions, the Little, Brown executive was told, came directly from J. Edgar Hoover.

Six more publishing houses turned Spartacus down. Fast was left with no alternative but to publish it himself. He and his wife turned their New York City basement into a shipping room and within four months they had printed and sold forty-eight thousand hardcover copies of Spartacus. Out of his basement!

The cover of Howard Fast's Spartacus.

Photo Credit: Charles WhiteThe “unbiased” critics ridiculed the book as poorly written, even though Fast’s other books were highly praised and had sold millions of copies around the world. The New York Times writer couldn’t figure out why Fast even bothered to write it, since “every schoolboy knows by now that Roman civilization began to suffer from dry rot long before the advent of the Caesars.”

Replying to that critic in Being Red many years after the fact, Fast wrote:

It would be a safe bet to say that before the appearance of my book and the film that Kirk Douglas made from it ten years later, not one schoolboy in ten thousand had ever heard of Spartacus.

Related: The 12 Best Movies Based on Books

While Howard Fast was shipping copies of Spartacus out of his basement, Dalton Trumbo was finally released from the federal penitentiary in Kentucky. Almost immediately he took Cleo and their three children and moved to Mexico.

I heard about this in the same way we all did, in hushed tones and whispered conversations.

“Did you hear about Dalton Trumbo?”

“Yeah, Mexico, I think.”

“That poor bastard.”

“Those poor kids.”

“I hear Eddie Dmytryk is cooperating now.”

“Well, what would you do if you were him?”

That was a question I didn’t have to answer, except for myself. No one was questioning my patriotism or keeping me from finding work. What would I have done if that had suddenly changed? Although Diana and I were, by this point, divorced, I was still responsible for two young children. Would I give up my career on principle? Go to jail?

Eddie Dmytryk did. At least it started out that way.

Like Dalton Trumbo, Dmytryk, an Oscar-nominated director whose nickname was “Mr. RKO,” was one of the original Unfriendly Ten. He had also refused to cooperate with HUAC. And he, too, was jailed for contempt of Congress in the same West Virginia penitentiary as Howard Fast.

On September 9, 1950, five days after his forty-second birthday, and after having spent months in prison, Dmytryk finally had enough. The warden witnessed his statement:

. . . in view of the troubled state of current world affairs I find myself in the presence of an even greater duty and that is . . . to make it perfectly clear that I am not now nor was at the time of the hearings . . . a member of the Communist Party . . . and that I recognize the United States of America as the only country to which I owe allegiance and loyalty.

Despite renouncing his views, he wasn’t released until December. Eddie Dmytryk returned to California a chastened man. He had been a Communist once, but he had no use for them anymore. Eddie’s attorney was Bartley Crum, a liberal Republican who later committed suicide because he, too, became tainted as a Commie sympathizer. Even Republicans weren’t safe from this guilt-by-association madness.

Left to right: Peter Ustinov, Charles Laughton, Kirk Douglas, Anthony Mann and Laurence Olivier on the set of I Am Spartacus!

Crum believed that the best way to get Dmytryk off the blacklist was by returning him to the scene of his “crime.” So on April 25, 1951, Eddie Dmytryk once again testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee. This time he identified twenty-six people as having been members of the Communist Party.

One of those he named was a writer named Arnold Manoff, whose wife, a twenty-three-year-old actress named Lee Grant, had made her film debut a month earlier in a picture called Detective Story. I was the lead. She had a small part; she played a shoplifter.

Lee was only a kid, a beautiful young girl with extraordinary talent and a big future. You could see it. She was so good that she earned a Best Supporting Actress nomination for her very first film role.

But because Eddie Dmytryk named her husband, Lee Grant was blacklisted before her film career even had a chance to begin. Of course, she refused to testify about the man to whom she was married, and it took years before anyone would hire her for another picture.

One day, Charlie Feldman—the top man at Famous Artists Agency—called and asked me for a favor. This was a first for me. Before I hit it big with Champion, Charlie often kept me waiting for hours when we had an appointment. I’d be told he was too busy—come back another time.

So when your agent calls and asks you for a favor, it’s one of those moments when you look at the phone in your hand like you’ve never seen it before. You think to yourself, How did it come to this?

“Kirk, I need you to do me a favor.”

“Name it, Charlie.”

“You know that director Eddie Dmytryk? He’s a client of ours and I’m trying to put a deal together for him with Harry Cohn at Columbia. It’s not going to be easy . . . I’m pulling a lot of strings. I think we can get it for him, but it’s gonna take some time.”

I was silent. I had played a fighter. I could see a punch coming.

Related: 13 Famous Memoirs Everyone Should Read Once

Feldman threw it. “Can you help him find something, Kirk? He needs work now. He’s got a new wife and a young family. His ex-wife took him for everything in the divorce and this whole Commie thing . . .”

“Done. Have him call me.”

“You mean it?!”

“Of course I mean it. I’ve got a lot of scripts that need reading. I can use the help.”

Charlie exhaled. “Thanks, Kirk. But you know . . .”

“Know what?”

“There are a lot of people still pissed off at him. I wouldn’t want you to get caught up in any of that.”

“Charlie, I’m a big boy. You’ve already sold me the car—now stop kicking the tires. Have him call me.”

Eddie Dmytryk came to work for me. He helped me with scripts. I took him out to dinner, to football games, to social gatherings. I wasn’t afraid to be seen with him in public.

Eventually, he got a movie and then Stanley Kramer signed him to a multipicture deal. (Yes, the same Stanley Kramer who bailed out on Carl Foreman. Maybe he was feeling guilty.)

After that I never heard from Eddie. Not even a postcard.

Fast-forward to 1953. I’m in Israel making The Juggler for . . . Stanley Kramer. He can’t wait for me to meet our director. Yeah, you guessed it. His name was Eddie.

The funny part is that Dmytryk never told Stanley that we’d met before. The job, the dinners, the games—all that had apparently slipped his mind in only a few years. So who was I to bring it up?

That was sixty years ago. If I knew then that he had named names, I’m not sure I would have given Eddie Dmytryk anything more than a swift kick in the ass. It’s one thing to protect your family, or even yourself. That I can understand. But ruining other people’s lives just to get your old job back?

Orson Welles put it best : “Friend informed on friend not to save their lives, but to save their swimming pools.”

Want to keep reading? Download I Am Spartacus! today.

Featured image courtesy of Universal International